Many of Pakistan’s distinguished and popular citizens, intellectuals and writers and journalists, have found themselves at various times branded traitors

It is easy to be branded a traitor in Pakistan.

Advocate diplomatic ties with Israel, argue for close government cooperation with India, question the role of Saudi Arabia in funding religious zeal in Pakistan, sympathise with the Kabul viewpoint on Islamabad’s security interests in Afghanistan, commiserate with the sentiments of nationalists in Balochistan and Sindh, express support for proper legal process for the likes of Shakil Afridi who helped locate Osama bin Laden, support calls for apologising to Bangladesh for the events of 1971, question the veracity of claims that Pakistan won all wars against India, criticise military courts in the presence of a fully functional normal judiciary, wonder aloud if secularism would not be a better bet in promoting equality of citizenry than embracing a single religion, or even support a former army chief’s trial for treason -- and you will automatically qualify for the dubious distinction of being traitorous and treasonous.

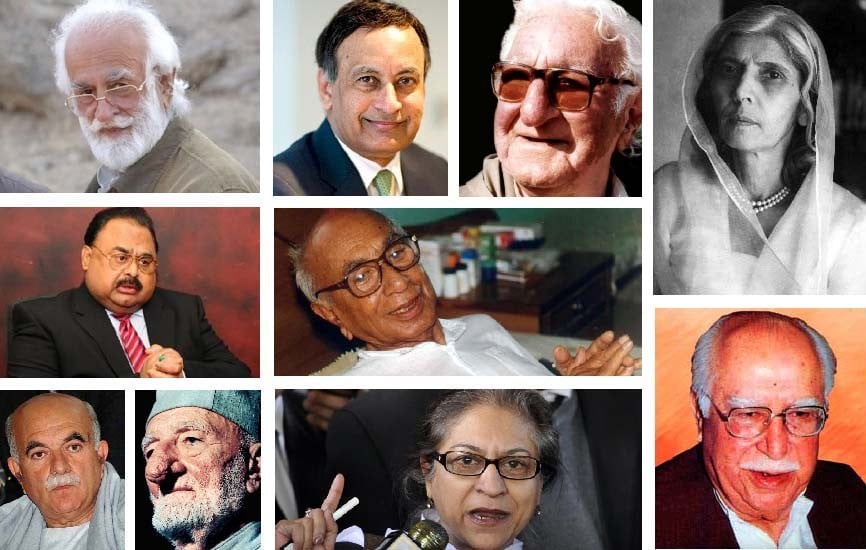

Many of Pakistan’s distinguished and popular citizens, for example politicians, such as Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Benazir Bhutto, Bacha Khan, G M Syed, Wali Khan, Mahmood Achakzai, Altaf Hussain, Fatima Jinnah, Hussain Suhrwardi, Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo, Khair Bakhsh Marri, Akbar Bugti, Ataullah Mengal, etc.; intellectuals and writers like Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Manto, Ustad Daman and Habib Jalib; activists, such as Asma Jahangir; diplomats, such as Hussain Haqqani; and journalists, such as Hamid Mir, Maleeha Lodhi and Najam Sethi, and others, have found themselves at various times branded traitors and accused of conspiracy, sedition, etc. Then there are other lesser known or unknown rights activists, such as Baba Jan, Sultan Raees and Fida Hussain of Gilgit Baltistan, Mama Qadeer and Farzana Baloch of Balochistan and others who face charges of sedition and treason or have been sentenced.,

Have these Pakistanis been, or are they still, traitors? Beyond accusations, allegations and suspicions, the measure by which they can be certified by the state as such is only in a court of law. This is where reality parts company from perception. Historically, primarily the crime of betraying one’s country is considered treason.

In traditional law, ‘proper treason’ or ‘high treason’ is the crime that covers only extreme acts against the country, such as killing the sovereign or subverting the constitution. Any non-extreme act against the country -- such as conspiracy, sedition or abetment -- is considered ‘lesser treason.’

Read also: What makes states and societies strong

In Pakistani law, high treason is articulated in Article 6 and only criminalises subversion of the constitution. Unlike in countries where murdering the sovereign is high treason, the Pakistani high treason article will not convict someone for murdering the head of the state. Terrorism, yes, treason, no.

But more importantly, Pakistani legal framework allows only the federal government to be the petitioner for treason. And, under Article 6, only a special court appointed by the government can try someone for treason but even if such a court convicts someone guilty of treason, only the parliament (not the court) can punish the guilty by passing a special specific-case law. The only person ever tried by the state for high treason in Pakistan is retired General Pervez Musharraf, in an ongoing case that theoretically continues but without confidence in culmination of the trial. We all know why.

Most of the other people mentioned above have been accused of "(lesser) treason" such as sedition or conspiracy against the state, armed forces, parliament or the government. Several have been prosecuted through formal charges and tried. Most were either acquitted or remained legally unaffected after failure of the prosecutors to proceed beyond procedural intimidation.

This is the reason Musharraf at one point proceeded with formal treason charges against Benazir but backed off after she threatened to disclose information related to his piloting of the Kargil fiasco. Musharraf did not proceed against Nawaz for treason (for allegedly trying to kill him for reportedly not allowing his plane to land) again because of damning details about Kargil that would become part of official special court record.

Instead, Musharraf tried him for hijacking -- the only law in Pakistan that carries a mandatory death sentence. Not even high treason will necessarily deliver you a death sentence. Today, neither Benazir nor Nawaz are considered as traitors but widely recognised and respected for their leadership and contribution to Pakistan’s democracy project. Ironically, Musharraf is the first Pakistani to be formally tried for high treason.

Among other charges, for which he was eventually -- even if farcically -- convicted by Ziaist courts, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was also accused of being traitorous. Ironically, he was convicted and hanged for ‘abetment’ to a murder, rather than any abetment, perceived or real, for treason. And yet the Bhutto trial, despite arguably being the most (in)famous trial in Pakistan’s judicial history, is not considered a precedent.

Earlier, the same Bhutto led his allies to politically persecute Baloch leaders like Bizenjo, Marri and Mengal for, among other charges, alleged treason. He also led accusations (and political persecution) of treason against Pakhtunkhwa leaders like Wali Khan as did General Yahya Khan before him. And yet decades after his hanging, Bhutto is given his due place in history as the first elected prime minister and author of the country’s only enduring constitution. His persecutor-in-chief, Zia, on the other hand, is widely vilified as perhaps the worst Pakistani ever born. Yahya fares little better.

Non-politicians have faced similar persecution for alleged treason but not only got rehabilitated in public opinion but also recognised for their professional omniscience and include journalists Mir, Sethi and Lodhi who all hold influential public positions currently. Even Haqqani, viciously persecuted by the security establishment, has not been denied renewal of his Pakistani passport a few years after being formally trialed for treason in the Supreme Court. Other luminaries, such as Faiz, Manto and Jalib far from being considered traitors that the state functionaries claimed them to be, remain some of the best representatives of an awami, jamhoori pluralist Pakistan that some quarters abhor.

It, then, appears that while it is easy to be branded a traitor in Pakistan, it is also not easy to prove one so in a court of law. Ironically, those never tried for treason, such as Zia and Yahya (and all their stinking abettors) have never needed any formal trials to be considered traitors even decades afterwards.