The only work by a Pakistani historian on macro-history and the concept of political power

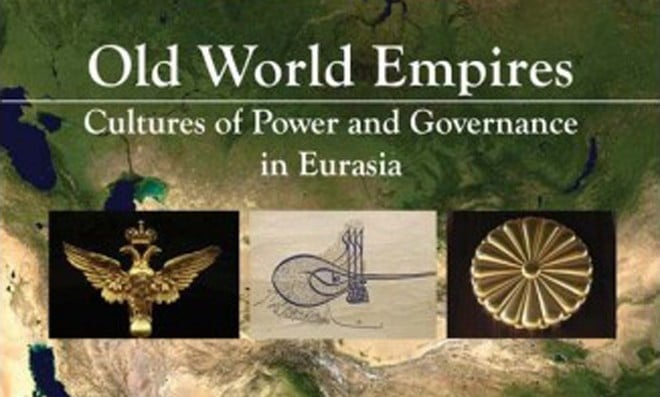

Most Pakistani historians write chronologically organised political histories of governance in South Asia by rulers neatly divided into periods -- classical, medieval, colonial, national -- with generous chunks devoted to major actors like kings, leaders of the freedom struggle and strongmen. Ilhan Niaz deviates from these norms: firstly, he writes macro- not micro- history; secondly, he does not work from archival sources but from published secondary sources; and thirdly, he writes about power and the concept of political power, and not about kings, conquerors and prime ministers as individuals. Above all his work is not confined to the subcontinent as such. It is about Eurasia i.e the whole of Asia and Europe.

Niaz focuses upon the "state as the basic structure or unit of analysis" (p. 9). He argues that the state developed two models in Eurasia: the continental bureaucratic state and the state of laws. The former have "arbitrary cultures of power" while the latter govern through laws and institutions which curtail arbitrariness.

In the former, the ruler believes that the wealth of the land is his and uses spies to root out possible opposition. He also uses a powerful bureaucracy to extract as much wealth as possible and to impose his own footprint on the land and its people. This footprint may be in the form of an ideology which the ruler favours and which, more often than not, favours the ruler’s usurpation of arbitrary power. The footprint may also be architectural, administrative and military. The ruler also favours the military which becomes the kingmaker, and sometimes the ruler, if the dynasty weakens. The ruler is arbitrary in the sense that he is not bound by any law or convention. He may punish his courtiers, bureaucrats and others simply by word of mouth and he is not really answerable to any authority even if he pretends to be.

There are two rough models to which most empires approximate. In the first, the ruler owns all land in theory and his henchmen, the aristocracy, get to collect rent and exploit the tillers of the soil until the ruler replaces them or gets rid of them. This is the model of India in the Hindu kingdoms, the Sultanate period and the Timurid (Mughal) period. China, Persia and Turkey follow the same model. Then there is the feudal model of Europe and Japan in which the individual lords have powers and keep struggling against the ruler and each other. In Europe they also had to struggle against the Church which was also a powerful landlord but in Japan the Church was completely subservient to the state.

In all such empires bureaucracy and the army helped the ruler consolidate his ascendancy till feudal centres of power were made to yield to the central sovereign.

Niaz’s major contributions are many but I will mention only three. First, he refutes the uninformed and prejudiced assertions of Pakistani writers who refer to Kautilya’s work, the Arthashstra, as reflection of the ‘Hindu mind’. Niaz has written about Nizam ul Mulk Tusi’s Siyasatnamah, a book about political advice to the Seljuk rulers of Iran, which gives just as unscrupulous advice to the Sultan as Kautilya gives to the Raja. Incidentally, Nicolo Machiavelli’s Prince also gives similar advice to the Italian duke who employed him. Indeed, it is not the advice which creates the arbitrary state but the arbitrary state which creates the advice.

Secondly, far from destroying everything in South Asia, the British rule actually brought us in contact with the best form of governance known so far in human history. To begin with, Britain too was feudal like the rest of Europe. But it evolved into a state based on "laws and a culture of power that consciously and subconsciously sought to minimize arbitrary power, diffuse authority and encourage autonomous institutions" (p. 455).

This unusual development -- which the author rightly terms ‘freak’ -- started with the lords defying the king in order to dilute royal authority in the shape of the Magna Carta which was signed by King John on 15 June 1215. The British model is to be commended because, except for such freak incidents such as the suppression of the Mau Mau movement, British rule over India and Africa was far more benign than that of other empires: Russia, Japan, China and Turkey.

His third achievement is that he disabuses those romantics who think revolution is a panacea for all ills. His descriptions of the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, the Chinese Revolution and the Iranian revolution should cure partial and romantic readings of history.

During all these revolutions, powerful and ruthless people came to the top and silenced dissent through utmost cruelty. France descended into a reign of terror followed by military rule succeeded by another bout of kingship. Meanwhile millions of Frenchmen died in useless wars. Russia descended into a cruel dictatorship in the name of the proletariat which killed millions by displacement, starvation and silenced the intellectuals and the dissidents out of fear. China under Mao suffered the same fate with the absurd cruelties of the Cultural Revolution. In Iran too, while the Shah’s tyranny could be opposed, the dictatorship of the Ayatollahs could not be since it is couched in sacred language.

This brings me to the overall achievements of Niaz as a historian. First, a survey of power on a canvas as broad as this -- practically the whole world -- is no mean task. Ilhan’s erudition is to be admired and his hard work saluted. Secondly, in this era of post-colonial bias against praising the British system at least in South Asia, requires much confidence and moral courage. Indeed, modern Pakistan is reversing many of the gains of British rule in the name of anti-colonialism, identity and religion.

Thirdly, for a Pakistani author not to pay the usual compliments to Muslim rule in India is surely extremely brave and unique. Fourthly, this is the first time a Pakistani historian defends the subject of history. He argues that history is the memory of the human race and is important in understanding our present and future just as childhood is for understanding the human personality (pp. 522-523).

The only thing which I have to offer by way of critique is that Pakistan has been touched upon only in passing while modern India gets all the bashing (well-deserved, of course). I am aware that Niaz’s first book was entitled The Culture of Power and Governance of Pakistan 1947-2008 and, having read it, I know that the author is an expert in that field but Pakistan should have been treated here as well. The second issue is that very little is said about Arab empires and the rise of Islamic militancy in them. A separate and fairly comprehensive chapter on this subject would have enhanced the worth of the book.

Notwithstanding these small reservations, this is a landmark study. In my view it deserves to be classified as the only work by a Pakistani historian on macro-history which can match similar works by Western scholars. This is no small achievement and one of which the author and Pakistan itself should be justly proud.