Hanif Mohammad did more than defy time with bat in hand; he carried the hopes of a new nation trying to find its feet post-partition

Pakistan lost its first truly great sports icon last Thursday barely a month after the demise of arguably, the greatest philanthropist in modern history, Abdul Sattar Edhi.

Hanif Mohammad passed away following a three-year battle with lung cancer at the Agha Khan Hospital in Karachi at the age of 81.

Today’s generation has scant idea, if at all, of how Pakistan, a cricket-mad country of nearly 200 million people, was hard-pressed to survive the odds when it won the full Test status five years into winning the independence in 1947.

Virtually unbeknownst to them, the title of ‘Little Master’ that has long been associated with Sachin Tendulkar, and before him, Sunil Gavaskar, was first bestowed on their diminutive-like Hanif Mohammed. This explains why any number of obit writers have had to use the prefix "original" to draw the distinction.

It is par for the course to trot out statistics to augment a sportsman’s worth when they wind down to a close. However, this remains little more than cold statistics in Hanif’s case, who had such mastery over his craft that bowlers would often come to grief, trying to dislodge him.

One of five Pakistanis in the International Cricket Council’s Hall of Fame, Hanif’s 17-year career (1952-1969) featured only 55 Tests -- probably, just a third of what a regular modern Test player may get a shot at -- with an average two decimal points short of 44. If ever, figures did not quite tell the story, this was it!

When a still green cricket nation began its quest to meet the challenge posed by the imperial cricket nations, it fell upon Hanif to anchor the ship -- right at the top of the order -- and he did this with such amazing patience, perseverance, commitment and consistency that Pakistan held its own against all odds, despite the lack of individual stars, apart from the charismatic pacer Fazal Mehmood.

Indeed, Pakistan impressed on its first tour to England in 1954, becoming the only Test nation to beat the ‘mother country’ on a maiden tour. Hanif had a stellar role to play in most victories with his characteristic defence that often dented the confidence of the opposite bowlers. It is a measure of the man that decades after he hung up the boots in 1969, Pakistan continues to struggle to find a reliable opener, much less a pair!

Talking of Hanif inevitably, takes you down the road of marathons. But one of those marathons -- spending a minute short of a thousand (some historians dispute this and say it was half an hour adrift) at the crease to save his country from a defeat most people suggested was carved in stone -- the sport has never seen again.

Now, cricket is a game where records are broken with such frenetic frequency that nothing is really considered impossible to conceive. But Hanif made a telling mockery of the adage about records meant to being broken with a rearguard defiance spread over three days in a six-day Test against the mighty West Indies in Barbados in 1958. It remains such an astounding feat that probably books could be written about it to try and make sense of the incredulity!

Well-nigh impossible as it is to encapsulate the whole drama in this space, a bit-part attempt can at least be made to comprehend the scale of one man’s mission impossible.

Pakistan had been bowled out for a paltry 106 in response to West Indies’ imposing 579 and forced to follow on the third afternoon. Only a fool could have conceived any result other than a Caribbean romp but Hanif hung on like a man possessed as one partner or the other deserted him at the other end and batted out time to such maddening frustration that a West Indian daily suggested tongue-in-cheek that only security could remove the 5’6 ‘giant’ Pakistani!

At just 23, Hanif scored a monumental 337, which still remains the highest of the triple centurion pole away from home in all annals of Test history, spanning 140 years. No batsman before or after Hanif has held such a long vigil.

He also held the record for the highest individual score in first class cricket for 35 years before Brian Lara eclipsed his 499 by a solitary run.

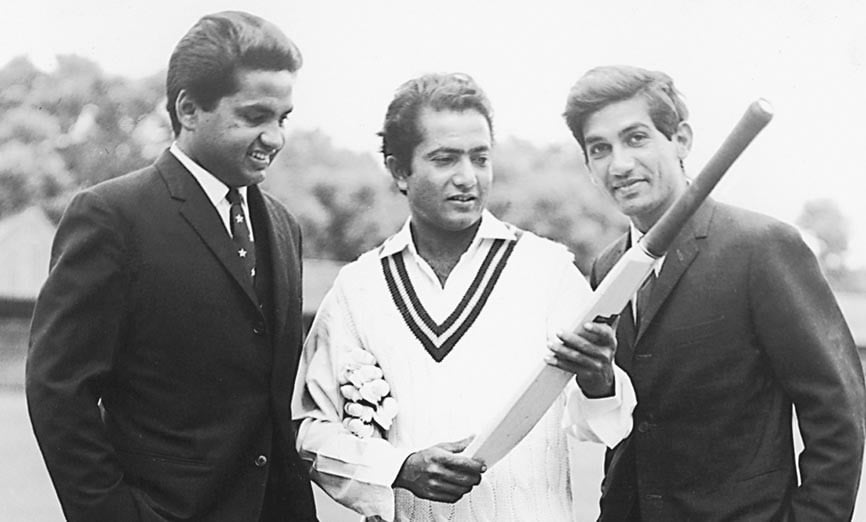

Hanif formed the famous quintet of Mohammad brothers, four of whom -- Wazir, himself, Mushtaq and Sadiq -- went on to play for Pakistan in Test matches whilst Raees, the fifth one, served as the 12th man once -- a remarkably uncanny milestone. But none matched the technique and temperament of Hanif although Mushtaq went on to become a successful and transformative captain.

Dropping anchor came naturally to Hanif as was evident when he top-scored with 187 at Lord’s in 1967 as captain (Pakistan were 139 for 7 in reply to England’s 369 before Hanif carried on with the tail to help it post 354) at a time when the feared English attack had been tipped to roll him over with short pitched music for his lack of height!

Often questioned about how he was able to concentrate for such unbelievably long hours, the Little Master put it down to playing ‘ball-by-ball’ as if it was that simple. Wisden Almanack, the cricket bible, Circa 1968, was able to draw on his bloody-minded doggedness, differently.

"As was his habit during times of strain on a tour beset by problems, he returned to his hotel room to listen to sitar music, the beauty of which is a mystery to most Western ears. He brought twelve tapes of it with him from Karachi as if aware that his philosophies about both captaincy and batsmanship could lead to loneliness," it wrote in selecting Hanif as one of the year’s five cricketers of the year.

As suspected this space -- much like time and space that Hanif seemed to defy while batting -- has proven insufficient to draw on his craft, and the man himself. Suffice it to say, they don’t make his like anymore.