We Pakistanis are not only ahistorical in our overall sensibility, worldview and political choices but we are apolitical too.

For most of us, politics is a vice, an art of deception and duplicity. The assertion that in our political choices, we are apolitical to the hilt is contradiction in terms. However, the validity of the above stated claim, as I will be arguing below, can hardly be doubted.

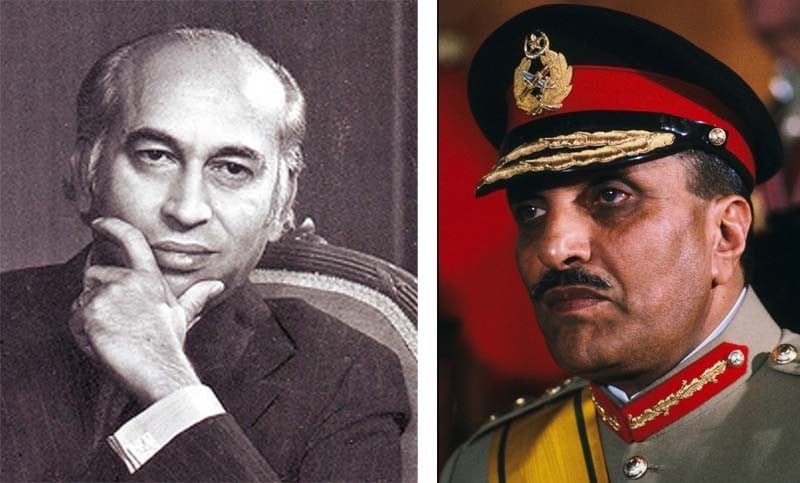

While talking in binary opposites of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (ZAB) and General Ziaul Haq, to signify two opposing trends of politics underpinned by the ideology of liberal left and religious right, punctuated with apolitical inclinations, Zia’s legacy has proved far enduring than that of Bhutto’s. Despite being known for his antipathy for politicians, Zia’s political progeny dominates the scene even after 28 years of his death, attesting him as the most influential figure in political history of Pakistan.

Thus, the recent modes of Pakistan politics had its initial source in a figure that was essentially apolitical if not altogether anti-political.

But that is not the only legacy of Ziaul Haq that has remained with us three decades after his death. Analytical appraisals of some of his policies form the theme of our today’s deliberation, which have impacted the state apparatus as well as people’s social behaviour.

Many liberal commentators of Pakistani politics have termed the tendency of blaming everything bad plaguing Pakistan -- religious fundamentalism, leading to terrorism and intolerance towards people of other faith(s) and sect(s) -- on Ziaul Haq as far too simplistic an analysis. They have a point because contextualising things like Zia’s policy of Islamisation from 1979 onwards is extremely important in order to make sense of it. This takes us back to the policy options available to ZAB which had brought Islam to the fore as an identity marker.

ZAB’s emphasis on Islam cannot be disputed. However, he balked at finding solution to political and economic problems in religious edicts. To him, Islam was the religion, democracy was the factor shaping his politics, and economic problems were to be addressed through the principles of socialism. During his 11-year-long reign, Zia over-emphasised the role of religion in all walks of life. With religion having moved to the centre-stage of public and political life, religious clergy gained extraordinary strength. Steadily, along with army generals, maulvis became the most significant galvanising force in the socio-political landscape of Pakistan.

Afghan jihad made the maulvis (particularly of Deobandi persuasion) impregnable. Now Pakistan is the only country in the entire world where the religious clergy has to be cajoled when any major policy decision is taken. The promulgation of the Hudood Ordinance and the Shariah Courts has hardly contributed any good to the society.

Such institutions have given unnecessary power to clerics many of whom are absolutely out of sync with the needs of the 21st century. Blasphemy law in the 1980s is yet another legacy of Zia. Bhutto, I reckon, could not have conceived of enforcing such a law.

Sectarian militancy was the most glaring of all the repercussions that beset Pakistan 1980s onwards. Zia and his coterie of advisers promoted sunnification in Pakistan at the behest of Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States, a factor conspicuously absent during Bhutto’s reign. The Zakat and Ushr Ordinance in 1980 drove a sectarian wedge into the body politics of Pakistan. Along with pushing Pakistan in the quagmire of Afghan jihad, this Ordinance was the most disastrous step ever taken by any Pakistani ruler.

Religious militancy has become a recurrent feature and drug rackets its epiphenomenon. The Zakat and Ushr Ordinance resulted in the crystallisation of sectarian denominations which led to the establishment of Sipah-i-Sahaba Pakistan and Sipah-i-Muhammad. Later, deadly outfits like Lashkar-i-Jhangvi operated and carried out target killing with impunity. The plural social character of Pakistani people has been decimated by pitting one sect against the other.

Another result of fanning the flames of jihad beyond the borders of Pakistan, in Afghanistan, eroded the geographical sanctity of Pakistan’s national borders. Now Pakistan as a nation state is in jeopardy and its armed forces are fighting hard to save it from the religious zealots (TTP and many of its offshoots), actually sired by Zia and his acolytes.

All said and done, Pakistan is striving to sustain itself from the adherents of the ideology that was unequivocally propagated by Zia regime and its political progeny.

Pakistani political scientists had been critical of feudals having sway over the Pakistani politics. It left little space for the urban bourgeoisie to play any meaningful role in the country’s politics. But under Ziaul Haq, a new breed of politicians entered politics. Many of them were businessmen, and they took to politics only to enhance their business interests. The non-party election in 1985 marked the beginning of such politics, which itself became a business. Corruptions, as a consequence, became an established norm without which politics was an impossible proposition. In fact ‘corruption’ and ‘politics’ became synonymous.

The 1985 elections marked the end of politics of ideology. Anybody espousing liberal left was hounded and persecuted. The sordid fact of Pakistan’s political history is the blatant intolerance exhibited by the right wing towards liberals and leftists. Under Zia, these elements were virtually squeezed out of politics if not out of existence.

Bhutto had treated his opponents in a loathsome manner but Zia perfected the art of maltreating his dissidents. Besides, Zia encouraged businessmen politicians to forge alliance with clerics to prevent the liberal-left from emerging as a formidable force. That alliance resulted into an advent of another phenomenon, signifying the conglomeration of capitalism and Islam which along with other things corrupted the clerics.

I will reiterate that Ziaul Haq with all his policy initiatives was the most influential ruler in the entire history of Pakistan. Bhutto came nowhere near his executioner, so far as the political legacy and its impact is concerned.