On S. H. Raza, one of the most prolific artists of the 20th century who created his own grammar rooted in the Indian tradition

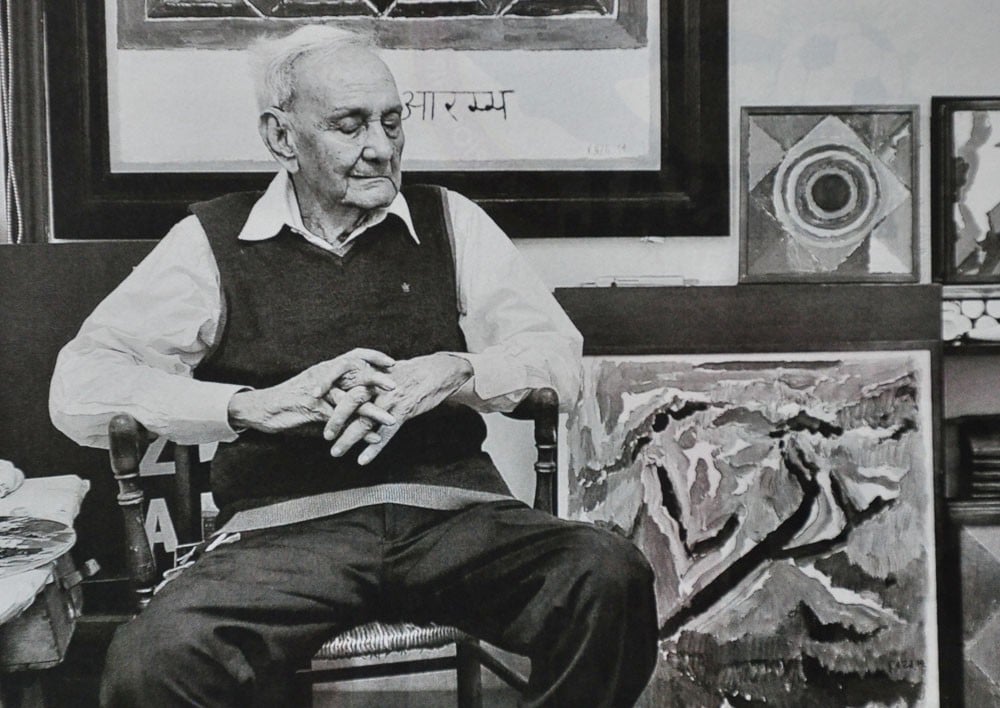

Syed Haider Raza, who legally used only Raza as his full name, passed away in New Delhi on July 23, 2016. In the weeks following his death, several prominent obituaries commemorated his unique persona and artistic vision as a painter.

Raza was one of the most prolific artists of the twentieth century. His vast body of work -- which encompasses several hundred paintings and drawings, from the early canvases of the 1940s to the final sketches he produced not long before his death at 94 -- represents the tireless investigations of an introspective artist who was obsessed with a handful of themes and objects, which he repeated incessantly, and who was, at the same time, engaged in continual experimentation with chroma and form. Perhaps no other modern artist explored the expressive properties of colour as Raza did throughout his extensive career.

In an age when success is equated with wealth and expansion, Raza set a different example. He used his intuition and eye consistently and with a degree of trust that inspired us to understand that real connoisseurship has little to do with privilege or class. Raza approached art not from taste or preference but from aesthetic judgment. This sounds simple -- but it isn’t -- because his engagement with artwork was a dynamic, ongoing, and challenging process. His success will always be measured in the intellectual and artistic wealth he gave to others.

Born in 1922 at Babaria in Madhya Pradesh, India to a Forest Ranger, Syed Haider Raza spent the formative years of his life observing nature before joining the Nagpur School of Art. A sojourn at Sir J.J. School of Art in Bombay opened up a whole new world of ideas for him resulting in the founding of the Progressive Artists’ Group. It was around this time that he met the acclaimed French photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson on a trip to Kashmir who said to him: "You have to learn the structure of a painting. Your painting lacks that."

Raza had had several exhibitions of his work in India before he left for Paris, France, on a scholarship to study at the L’ Ecole des Beaux Arts. Influenced by the Post-Impressionists, and German Expressionists such as Kirchner, he spent years learning to understand how Cezanne constructed his paintings. In 1956, he won the much-coveted Prix de la Critique from the French government; and in 1962, he was invited to teach at the University of California at Berkeley where he worked with Sam Francis. Much enamoured by the American Abstract Expressionists, especially Mark Rothko, he remarked: "Rothko’s work opened up lots of interesting associations for me. It was so different from the insipid realism of the European School. It was like a door that opened to another interior vision."

Raza spent the rest of his life between Paris and Gorbio until his return to India in 2010 where he was awarded Padma Shri by the Indian government -- one of India’s most prestigious civil awards.

Raza’s complexity was both internal and external. He was very private yet public. He sat in his studio at the front desk. If you called, he was often the man who answered the phone. It was he who learned and grew with what was on his easels and exhibited in his space. "An artist’s life is solitary. I work in complete isolation", he confessed.

Art historian George Kubler referred to ‘precursors’ and ‘rebels’ to describe what he viewed as the two types of innovators in the history of art. "The precursor can have no imitators", Kubler wrote. He "shapes a new civilisation; the rebel defines the edges of a disintegrating one." That Raza could have been both inimitable precursor and edge-riding rebel is a testament not only to the strange contours of his era but to the unparalleled dazzle of his thinking, the push and shove of his work, and its sweeping leaps and bounds.

As a warm Parisian August afternoon pressed up against the windows of the artist’s studio at Rue de Charonne in Paris in sixteenth arrondisement, Raza reminisced about his life, his art, his inspirations and his hopes. Scattered around us were signs and symbols of a life well-lived on two continents and in two cultures -- the sketch that was a gift from his friend and fellow-artist, F N Souza, a reprint of Picasso’s ‘Two Friends’, the frayed garland on a photograph of Mahatma Gandhi, and two sculptural paintings by Janine Mongillat, his muse and wife till her death in 2002. Raza spoke softly yet animatedly, rising occasionally to point out a detail in a painting or to strike a pair of cymbals to illustrate a primordial sound, the audible analog of his ‘Bindu.’

The series of paintings referred to as the Bindu Paintings began as a result of the trip Raza made to India in 1975. Linked to the excursions to Ajanta and Ellora Caves, ‘Bindu’ became the beginning, the seed from which the tree grows, the egg from which comes the child. Raza admitted that Bindu "is to painting what Om is to meditation and music". The story, however, goes further back into time when as a child in the village of Kakaiya, Raza was taught to look at a dot and concentrate by his Ustad Nand Lal Jharia. Later on, Raza proclaimed, "It’s there that I started seeing".

Why do circles, ovals and rectangles in Raza’s oeuvre continue to inspire us? At first glance, these geometric compositions, often divided into quadrants, may appear to move away from the complexity of the real, and from the nuances, interruptions and surprises that the real holds. However, the compositions on Raza’s canvases express the most exalting and enigmatic encounter extolled in cosmology and sung by poets: the union of the feminine and the masculine. The western mind will immediately conjure up an image of a couple locked in embrace. But in the context of Indian culture, such an embrace is only one manifestation of a union whose dynamism lies in language, in the word (feminine) linked to the ritual (masculine), in the waters and the sun.

A fundamental formula of Mozart’s helps to shed light on Raza’s work: "I assemble notes which love one another." The forms Raza places on his canvases also love one another, not only because they are both seed and matrix, but also because they are held together by an audacious plastic harmony. Circles and triangles play the same score, joined by a sumptuous game of colours, both monochrome and contrasting.

Like every great painter, Raza has created his own grammar, a homogenous art drawing upon signs that have their roots in the Indian tradition. The circles, often black, but equally red, yellow, blue; or, more recently, pale and neutral as if enticed by silence -- are imbued with an infinite density. They are the creative energy. This energy, says Raza is "the visible form which contains all the essential elements of line, tone, colour, form and space." The triangles, terraced like an eternal enchantment, are the female receptacle while Kundalini or the energy of awakening is in the crossing, coiled serpents or in the concentric circles.

Long before the attention he would enjoy during the last decade of his life, Raza was asked if his work would end once it was fully understood -- what would happen if the ‘not yet known’ finally became comprehensible?

"Painting is pouring out part of yourself on the canvas. The self disappears. Nothing else matters at that moment except the creation. My work reflects Indian mysticism and Hindu philosophy. The Bindu is the primordial form; the colours I use represent the panch tattvas. I trained in France, so the language is formalistic but the subject is rooted in India."

Raza seemed to represent a cul-de-sac to many: His detractors dismissed him as a sideshow maverick while his admirers hyperbolically described him as the destroyer of modern art. Does he send us back to face a void with no landmarks, no date or limits, no beginning nor end? Relentlessly looking ahead rather than back, he was always an end and a beginning.