He is an original. You don’t become one by striving hard for it. If you work assiduously to create such an impression, it is very likely that the readers will become suspicious of your intentions and think that you are too clever by half. Or you may become excessively abstruse and solipsistic, and the readers will say: "Here is a book I can’t pick up once I put it down."

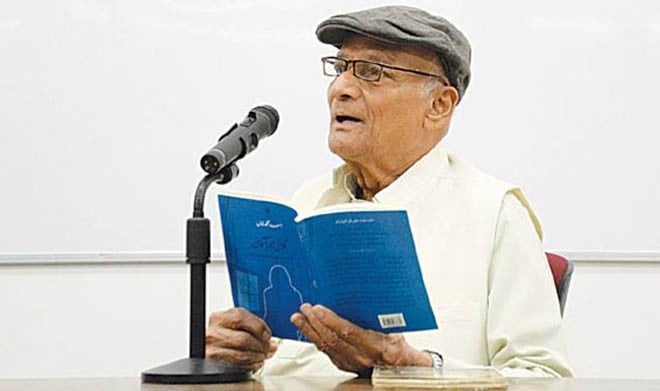

Asad Muhammad Khan is one of our originals. He writes as if stories and anecdotes gravitate towards him naturally. There is no effort involved. All this may be deceptive. As we read him, we scarcely notice how much exertion it must have entailed, the careful revisions, excisions and additions, the unending search for the exact word, the right phrase. Instead his fiction looks like a smooth, swift flow. As readers we can rest on our oars and drift along. Every good writer, consciously or unconsciously, creates illusions. Yeats put it most aptly.

I said, "A line will take us hours maybe,

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching had been nought."

So where does Asad’s originality lie? It is to be seen in a medley of characters, extraordinary or plain, lean and mean, chivalrous and brave, cunning or simple, content or fretful, out of sorts and ready to head for any situation that appears to be the least promising. In short, heedless seekers of thrills, as so many of us are or can be. It is to be found in his landscapes, minatory, inhospitable or unfamiliar, or in the situations he creates, wherein people are trapped or in a quandary or fatalistically indifferent.

Not a nice view of the world we live in. But then the world itself has never been a friendly place. We battle on in an aura of hostility. Survival at best is a remission. And all this writing stamped with an unmistakable authority. Read only a few pages of Asad and you would know he is in a class of his own. He possesses a fine ear. His dialogues always startle and sparkle. The prose is sprinkled with words you won’t find in the dictionaries.

It is a pleasure to read whatever he writes, travelogues, reminiscences interlaced with autobiographical asides or fiction in which reality is lit up with ultraviolets and infrareds.

It is remarkable how many of his characters, for some reason or another, wear a persona (an actor’s mask). I can’t name them all. There is Mai Dada, although merely a Hindu oil-seller, who passes himself off as an authentic Pathan and a Muslim (and mournfully notes that there have been no murders in the family once its members got educated). There is the doubled-faced Darogha Basheer in ‘Naseebon Walian’, Jani Mian who poses as a moronic landlord, infatuated with a courtesan, but is a secret agent employed to break up a ring of opium smugglers, Ally Gujjar busy inventing fresh identities for himself, a man in jail who claims that he is charged with rape but is no more than an ordinary criminal handling stolen goods. Laji Bai who wants to forget that she was once a famous singer. In ‘Circus ki Saada Kahani’ the main characters are a vicious and subversive lot and the story has an air of a politically symbolic drama about exploitation.

Some of his fiction is historical, focusing on the Middle Ages when Khiljis, Tughlaqs and Suris ruled over northern India. The realism and dramatisation are amazing. Some of the details could not have been gleaned from historical sources. So where do they come from? Maybe from sheer imaginative ingenuity.

Sher Shah Suri fascinates him a great deal. Sher Shah was a truly remarkable man. His untimely death and the weakness of those who succeeded him allowed the Mughals to make a comeback. The Pathans never had an opportunity afterwards to oust the Mughals or challenge their hegemony. It is an old quarrel: the Mughals and Pathans at daggers drawn. And no secret either as to which party Asad’s sympathies relate.

Had Sher Shah been able to rule for a couple of decades, the history of India, at least of its north, may have taken a different course. These suppositions, "what if … " in nature, are impossible to prove and belong to the realm of fantasy. Asad, on the other hand, should he so wish, can write a very credible alternate history, couched as fiction.

Two or three stories are worth some attention. ‘Ghus Paithya’ (intruder) is about two outcasts, one a Muslim Pathan, the other a low-caste Hindu, who used to sell things made of lac. Homeless, abandoned by others as despicable men, they somehow find comfort in each other’s company, generating a sort of synergy. They live in an ancient graveyard, making do with scraps and leftovers. That is, until tragedy overtakes the city of Bhopal as isocyanate gas kills thousands. The pair tries to escape the deadly gas but fail and each man, as he dies, makes a plea to the powers above, that his companion also should find a safe haven in the world to come. Altruistic SOBs, Asad remarks, trying to trespass on Elysian Fields. And why not! After a hell of a life a little bit of consolation.

In ‘The Salon’ the Murshid of Hidayatullah, a wrestler, opens a hairdressing salon in a disreputable place. Hidayatullah wants the Murshid to give him a haircut and a shave. Nothing happens. The Murshid acts as if the wrestler does not exist. The wrestler stands outside the salon, waiting, unshaven, his face lined with anxiety. Days go by. At last the Murshid teaches the wrestler a lesson in humility and he is forgiven. "It’s your turn now," the Murshid says. The ending is brilliantly conceived and depicted.

‘Aik Sanjeeda Detective Story’ is set way back in history. The period is not specified. One of the main characters is a Portuguese physician. Therefore it can be safely assigned to the 16th century. A nobleman attached to the royal court notices the Portuguese behaving in a suspicious manner, decides to tail him to clear up the mystery and is himself trapped in a maelstrom of paranoia, intrigue and poisonous concoctions. There is no way out. There are rooms after rooms, like parallel universes, the same scene being enacted, only the bargainers differ. The sinister atmosphere is cleverly conveyed. Simply breathtaking.