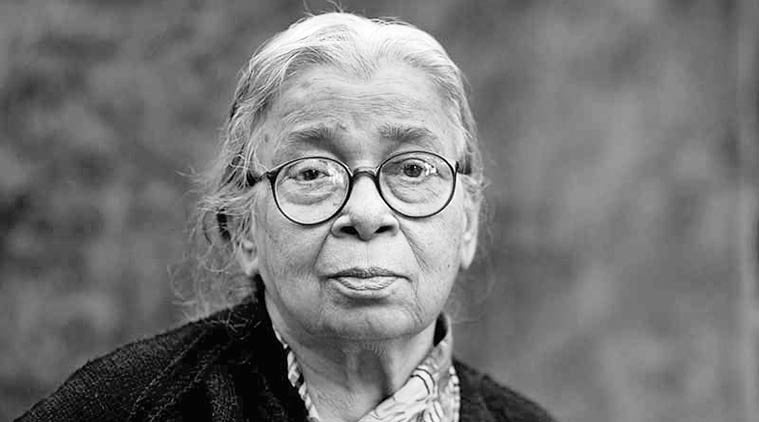

A writing career that spans at least sixty years, Mahasweta Devi wrote stories that make you feel the pain of the oppressed pierce your bones

If you want to know what happened, read history -- so goes the saying -- but if you want to understand how it felt, read literature. You know that activists fighting for rights disappear, teachers are shot dead, intellectuals’ mutilated bodies are dumped, women are assaulted, girls burned alive, homes destroyed, and the weak brutalised. But have you ever felt it? Read the stories of Mahasweta Devi and you will feel the pain piercing your bones.

Devi died in Kolkata on July 28, 2016, at the age of 90 and left behind over 120 books, comprising 20 collections of short stories and around a hundred novels.

Being born in an artistic and well-to-do family is no big deal, what requires valour is the ability to unmask the faces of the oppressors and become the voice of the oppressed. And that’s what Mahasweta Devi did for at least 60 years of her life, not only as a journalist and writer but also as an activist and advocate for the most backward classes in India. Her family had artistes and writers spread all over. Yet, her upper-caste Brahmin background did not prevent her from associating with the tribal people, the so-called ‘criminals’ and with the lowest of the low within Indian society.

She was born in Dhaka and had gone through the pangs of migration that sensitised her to the plight of those who have to leave their homes, to flee persecution or simply for food and shelter. Both her parents were writers; the noted filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak was her uncle. She studied at the university founded by Rabindranath Tagore in Santiniketan from where she finished her Masters in English Literature and married Bijon Bhattacharya, a prominent film and theatre personality and one of the founding fathers of the Indian People’s Theatre Association.

If you are a fan of the Indian movies made in the 1940s, you can recall Dharti Kay Lal (1946) -- directed by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas -- based on Bijon Bhattacharya’s play.

Divorcing her husband in 1959, she embarked on a literary journey of her own. She travelled a lot and did extensive research for her first book in Bangla, Jhansir Rani (the Queen of Jhansi) that was published in 1956 and launched her prolific writing career. She also became a regular contributor to several literary magazines mostly in Bangla and dedicated herself to the cause of oppressed communities within India.

Women were her particular concern -- be it a princess or a prostitute. She found courage in all things female. Many of her women created a strong screen presence when put on the celluloid; Vyjayanthimala as a dancing girl, Laila-e- Aasman, based on her short story, left an enduring impact on film viewers in Hindi film Sunghursh (1968) with Dilip Kumar. The story is set in Banaras and Calcutta of the late 19th century, and revolves around the theme of religious exploitation by the priests.

The Naxalite Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s was also an important influence on Devi’s work. Her most moving story about this movement was ‘Hajar Chaurashir Ma’ (Mother of 1084). This is the story of an upper-middle class woman whose world is changed forever when she receives a midnight call by the police to identify the body of her son who has been killed for his Naxalite beliefs. Her husband is more interested in protecting his family’s ‘respected’ name in society; the mother goes to the morgue and finds a tag with number 1084 tied on her son’s toe.

There begins a new struggle for the Mother of 1084, she is not allowed by the security forces to take the body home and perform the last rites for her son. The body shows the signs of severe beating and a brutal murder. The police keep coming to her home, conduct searches, tear apart mattresses, take away her son’s books and diaries. She realises how detached she was from her son who had a desire to change the society, but nobody in the family shared his enthusiasm to fight against oppression.

This has also been made into a Hindi film Hazaar Chaurasi ki Maa (1998) by Govind Nahalani with Jaya Bachchan and Nandita Das in their best roles. While reading this story or watching the movie, one recalls the Russian novel Mother by Maxim Gorky; also made into a movie in 1926.

Though there have been numerous translations of her work, arguably the best are by Anjum Katyal and Gayatri Chakravarty Spivak, both women of strong literary merit. You may start with After Kurukshetra which is a collection of three stories translated by Anjum Katyal, each of which centres around women in the aftermath of the Kurukshetra War from the Hindu religious epic Mahabharat. If you are familiar with the treatment women get in this saga, you will surely enjoy the way Mahasweta Devi raises important questions by her creative genius through the women in the three stories.

‘Rudaali’ is another story that makes you feel the pain of a woman who can’t cry despite her repeated misfortunes. In extreme poverty, her husband dies after a cholera epidemic in her village; she has no means to spend money on his cremation and other rituals demanded by the local priest who threatens her with eternal punishment if she doesn’t pay him 50 rupees for the salvation of her husband’s soul. She begs the local chieftain who demands 15 years of bonded labour in return for 50 rupees; she has no choice and agrees to this long labour; sounds familiar again? Gulzar converted this story to a brilliant screenplay directed by Kalpana Lajmi in 1993 with Dimple Kapadia.

Two more stories worth-mentioning are ‘Choli Ke Peeche’ (Behind the Bodice) and ‘Draupadi’. In Hindu mythology Draupadi has a religious role as the woman who has to share her body with many men. Devi’s story is set in the struggle of Indian villagers against security forces who ultimately capture the rebellious Dopdi, age 27, and repeatedly violate her body to the extent that she faints again and again and finally refuses to put any clothes on herself telling her guards that there is no man around to feel shame from.

The story leaves you in tears and rage. One recalls ‘Khol Do’ by Saadat Hasan Manto on a similar theme, but Dopdi’s political orientation and defiance makes her an unyielding character.

Finally, ‘Behind the Bodice’ is an unforgettable story with the once-popular Hindi song ‘Choli Ke Peeche’ as the trigger. The song, apparently created for the light entertainment of men, takes up a brutal new meaning in the story.

Devi’s writing style is seldom linear. With signature staccato dialogues, she hits you in an iterative fashion. Indeed if you want to know what happened, read history, but without literature you can’t understand how it felt.