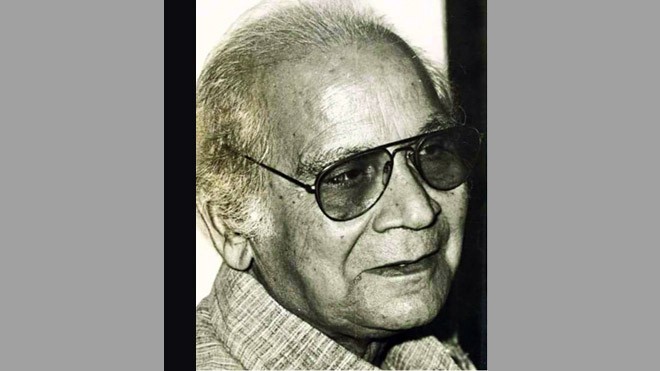

Understanding the life and legacy of Sibte Hasan

The year 1916 was very kind to the Indian subcontinent. Notwithstanding the fact that the third year of the First World War was raging on, three distinguished personalities from the fields of art, critical prose and literature were born: the great painter and innovator of abstract art, Shakir Ali; one of the region’s greatest short-story writers and poets, Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi; and Sibte Hasan, Pakistan’s own Gramsci and gadfly.

In an article published in The Guardian this past June and much circulated on the social media, Sarfraz Manzoor credited the eminent Pakistani writer, Saadat Hasan Manto, with predicting the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Pakistan and being prophetic about the direction of Pakistan-US relations.

Manto didn’t live long in the independent Pakistan, but it was public intellectuals like Sibte Hasan who educated generations of enlightened, secular-minded, progressive Pakistanis and, thus, prepared them for the long dark nights of military dictatorship and the rise of fundamentalism and obscurantism.

Sibte Hasan was born in 1916 in a village called Ambari in Azamgarh District of Uttar Pradesh. He came from a crusty zamindar family which boasted of traditions of intense loyalty to the British as well as outright rebellion to them, in the 1857 War of Independence. He describes the influence of rationalist scholar Niaz Fatehpuri while still a schoolboy in the following words:

"During (my) school education, the favours of Allama Niaz Fatehpuri upon me, I cannot ever forget. In the seventh class, for the first time, I read Niaz Fatehpuri sahib’s magazine Nigar, after which I brought and read his books. Reading Niaz Fatehpuri’s writings radicalised my thought, the ability to think with my own mind away from blind following. I learnt this from Allama Niaz Fatehpuri that whatever appears to be correct, accept it, whatever appears incorrect, reject it. It is because of his writings that I became wary of mullahism. Mullahism is a very bad thing and it has created a lot of damage."

The young Hasan was further radicalised towards rejection of his family values, attracted to rebellion and revolution by the contradictions within his own family.

Read also: In pursuit of enlightenment

He says, "Then I saw one or two very extreme events. Once I had gone to a relative’s place. I was returning from there in the evening that I saw a commotion at the house. There was a huge neem or guava tree outside our house. A man was tied to it and my late younger paternal uncle had a paper and he was forcibly affixing the farmer’s thumb on it and the latter was screaming. His thumb was moving because of the screaming and uncle was furiously trying to affix it to the paper by making it static. God knows what happened to my late uncle, perhaps seeing my reaction or just by seeing me he felt embarrassed and let go of the man immediately. He went away sobbing. I still remember this incident and whenever I think about it, I feel very sad. I did not have the courage to say anything to uncle but I felt very bad."

After doing B.A. from Allahabad University, Hasan went to Aligarh Muslim University where he studied law. This was again a formative period in his life because here he came into contact with the Communist Party of India (CPI) and became a communist after reading the work of Dr K. M. Ashraf, a distinguished historian very close to the CPI.

This period in young Hasan’s life is immortalised in eminent Progressive writer, journalist and film director Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s autobiographical novel Inqilab, in which the protagonist Anwar, an Aligarhian like Abbas meets a comrade ‘Subhanovsky’ who lectures the former on the finer points of libido, and inhibitions, as well as terms like dialectics, bourgeois, proletarian, Oedipus complex and fixations. There is no doubt that comrade Subhanovsky is modeled on Sibte Hasan.

From Aligarh, Sibte started a distinguished journalistic and literary career, mentored by two towering personalities of the Urdu firmament, Qazi Abdul Ghaffar, famed for his satirical Laila kay Khutoot; and Maulvi Abdul Haq, celebrated to this day as Baba-e-Urdu.

Read also: Editorial

This intellectual journey is lovingly and delightfully recorded in Sibte Hasan’s memoirs Shehr-e-Nigaraan, the title referring to Hyderabad Deccan, in his own words, "where my consciousness became aware of the beauty of life and where I learnt to love human beings". It is also an unforgettable record of Sibte Hasan’s days spent in the company of remarkable comrades and contemporaries like the leading Progressive poets Makhdoom Mohiuddin and Ali Sardar Jafri, and an accurate picture of the crumbling milieu of the feudal, oppressive Asif Jah dynasty.

The heady, creative days of Hyderabad Deccan were interrupted in 1946, just on the cusp of the partition of India, to go to the United States, where Sibte Hasan completed his M.A. in Political Science from Columbia University in New York. The Cold War had just begun and Sibte Hasan too became a victim of the McCarthyite witch-hunts as a result of which he was first arrested, and then deported.

He arrived in Lahore in 1948 and started work with the newly-minted Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP) together with his comrades Sajjad Zaheer, Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Ashfaq Beg. However, the CPP was later banned on a trumped-up charge of attempting to overthrow the Liaquat Ali Khan government.

Sibte Hasan was arrested along with scores of comrades in 1951 in the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case and remained in jail until 1955. After Pakistan’s first military coup in 1958, led by General Ayub Khan, he was again arrested. Thus, the comparison to the famed Italian Marxist thinker, Antonio Gramsci, is not accidental; however unlike Gramsci, Sibte Hasan’s internment mercifully proved temporary and he went on to research and write his seminal works.

It is not possible in this short tribute to do justice to each of Sibte Hasan’s 11 works in Urdu and the lone one in English. Most of these works, like Moosa say Marx Tak, Naveed-e-Fikr, Maazi kay Mazaar, Shehr-e-Nigaraan, Pakistan mein Tehzeeb ka Irtiqa and Inqilab-e-Iran require separate discussions and expositions.

The first four aforementioned books have gone into almost 20 reprints each, making Sibte Hasan a bestselling writer and a household name in Urdu popular literature; an astonishing feat for a thinker who by his own admission shied away from poetry and fiction, and was attracted to the critical prose essay.

The life and legacy of Sibte Hasan can be understood in three ways: as one of the founders of the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) in colonial India; as one of the leaders of the CPP in Pakistan; and as one of the pioneers of progressive journalism in Pakistan while working for such distinguished newspapers as Imroz, The Pakistan Times and Lail-o-Nahar.

There are also two other, much less-acknowledged ways to understand the significance of Sibte Hasan as a public intellectual who despite his command over Urdu, Farsi and English consciously chose to write in Urdu. The first is as one of the most important protagonists in the battle of ideas in Pakistan which had initiated in colonial India between the followers of the two ‘Syeds’: namely Jamaluddin Afghani and Sir Syed Ahmad Khan; then between the followers of Muhammad Iqbal and Maulana Maududi.

While in the colonial India, these debates were limited to the role of Islam in public life and affairs of the state; and the strategies of anti-imperialism and British (or Ottoman) loyalism, in the newly-independent Pakistan, the debates encompassed the role of Urdu, ‘Pakistaniat’, and by extension modernity and backwardness, ‘Islam’ and ‘Progress’, and the role of nation and culture.

On one side were popular, but nevertheless important writers like Naseem Hijazi and many ex-Progressives (it would be best to call them renegades) like Muhammad Hasan Askari, Akhtar Hussain Raipuri and M. D. Taseer, all of them writing in Urdu; on the Progressive side were equally distinguished names like Safdar Mir, Manto, Qasmi and Sibte Hasan.

Sibte Hasan entered the debate with the publication of his book Pakistan mein Tehzeeb ka Irtiqa in 1975. Unfortunately, despite the importance of this topic, the book continues to be ignored even by sections of the Pakistani left. In this writer’s humble opinion, it is Sibte Hasan’s most important work specifically dealing with Pakistan, and whose relevance increases as Pakistan moves towards celebrating the 70th anniversary of its independence next year.

The second way in which Sibte Hasan appeals especially to my generation is his spirited defence of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and Muhammad Iqbal against the dogmatists of both the right and the left. In fact, Sibte Hasan rehabilitated their role as the predecessors of the Progressive tradition.

Sibte Hasan’s great contemporary, Khawaja Ahmad Abbas has referred to the former in his autobiography I Am Not An Island as ‘one of the "Russians" or communists…propagating communism through literature,’ which is quite unfair given that Sibte Hasan was one of those who not only vehemently protested the expulsion of writers like Manto, Askari and Rashid from the PWA; but also survived the destruction of the CPP following its banning, as well as the Sino-Soviet split later on with his prestige intact, and because of his immense stature was acceptable to every camp.

In an exchange with the famous modernist, free-verse poet Rashid, Sibte Hasan answers to some of the former’s objections and allegations regarding communism and freedom of expression:

"As far as the personal freedom of any writer is concerned, I wholeheartedly agree with his view, rather I think that personal freedom is the birthright of every man, whether he is a writer or a non-writer, since it is only in an air of total freedom that man’s creative abilities and natural tendencies can prosper. Submission really reduces his life to a drying stream. How well has Rashid sahib put it in his preface to ‘La-Insan’ that, "Slavery reduces both the price and the stature of an individual. Both love and thought are reduced to being wanting and deficient." But his accusation that Progressive people advise the poet to withdraw from his individual right in the choice of topic, is unfounded. Which Progressive poet of India or Pakistan has instructed which poet or artist to create this kind of literature and not to create that type of literature. Although the creative man is strange because even while obeying orders he can create great masterpieces. After all, Ferdowsi wrote the ‘Shahnameh’ at the request of Mahmud Ghaznavi; and Michelangelo and Raphael painted the frescoes of the Church of Rome at the order of the Pope; and Shakespeare wrote most of his dramas for the sake of the belly on the direction of the theatre owner. Just yesterday Urdu poets (including Ghalib, Mir and Sauda) used to write ghazals-on-demand on rhyming couplets. This does not mean that we are in favour of order, instruction or advice. But my view too is that every artist should always follow his ‘vision’. Every person knows that no one ever told Faiz, Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi, Farigh Bukhari, Ismat Chughtai, Krishan Chander or other Progressive writers to write this or that kind of story, poem or ghazal; in fact everyone followed their ‘vision’ according to their own philosophy of life and aesthetic taste." Here Sibte Hasan comes off as anything but a dogmatic communist.

The year 2016 is being celebrated as the birth centenary year of Sibte Hasan. He was not only Pakistan’s own Gramsci but also its gadfly, constantly provoking and questioning its elite and people alike with uncomfortable questions in the best Socratic tradition. Yet, he has been studiously excluded and ignored by all the major literary festivals celebrated in Pakistan this year, including the city where he chose to live his long and productive life.