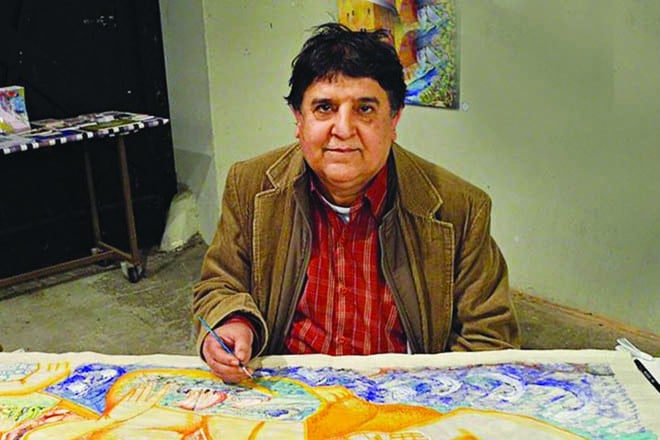

In conversation with artist and activist, Mohammad Bugi Ansari about his art, and passion for the cause of the Kalash

Mohammad Bugi Ansari was recently visiting Pakistan after a gap of several years. A bohemian and an artist who lives abroad, Bugi has led life on his own terms; and has also been a dedicated activist for a cause close to his heart: There is perhaps no other voice in Pakistan that has been raised so vociferously and continuously for the rights of the Kalash people as that of Bugi. The indigenous lifestyle, culture and religion of the Kalash that live in three beautiful valleys of Chitral namely Rumbur, Brumbret and Birir, in Pakistan’s northern areas is threatened by insensitivity and rampant intolerance particularly of those bent on converting the Kalash from their ancient religion to Islam, thereby obliterating their centuries-old way of life.

Bugi studied Fine Arts at Government College, Lahore, "under a gold medalist teacher, Mr Minhas, who had studied at the Fine Arts Department of Punjab University." Having known him as a fellow artist since the 1970s, I was meeting him after over 40 years, and had several questions in my mind. Bugi was both frank and forthright.

The News on Sunday: When did you first go to the Kalash valleys, and how long did you stay there?

Mohammad Bugi Ansari: I first went there in 1980, and stayed for three months. I was absolutely fascinated not only by the beauty of the landscape, but also by the uniqueness of the people. I spent my time drawing and painting and learning about their customs and rituals.

TNS: Did the Kalash speak any Urdu then?

MBA: Very few people spoke Urdu back then: only the ones who had gone to the cities to work. I picked up their language.

TNS: When did you begin your activism for the Kalash, and why?

MBA: It was extremely difficult to reach those valleys in 1980. The Kalash then were quite isolated and therefore pure in their lifestyle. There were no wild tourists to throng them or to make fun of them. A barter system was in full-swing, therefore there was no need to use cash money to buy anything. Their houses remained unlocked, as there were no thefts. The Kalash not only respected each other, they also respected the non-Kalash. All of a sudden, the Afghan Mujahedeen came to live in those areas and started cutting trees, as the timber mafia moved in. The Kalash culture and their environs became threatened. I was very disturbed by these developments, and therefore felt deeply for their cause.

My first lecture on the subject was at the Goethe Institute, Karachi. News about my experiences with the Kalash soon spread like wild fire. I was invited to give more than 20 lectures. For the next eight years I travelled all over the world, spreading word about these wonderfully unique people of our country.

In 1989, the Karachi-based Mr Byram Avari, a member of another minority community, took the subject of the Kalash to heart and offered me half of the cost for working in the Kalash areas for a month. I went there and, once again, stayed for three months, spending time in the Kalash valleys and also in the adjoining areas. I have returned to their valleys off and on over the years, but my recent visit was after a gap of several years.

TNS: Tell us about the origins of the Kalash as, I believe, this is still being debated.

MBA: The Kalash religion predates the other great religions of the world. However, the most common myth about them, I guess due to their white skin, golden-brown hair and blue eyes, is that they are descendants of Alexander the Great who was in the subcontinent in the 4th century BC. Many historians, however, believe that they are an indigenous tribe from the neighbouring Nuristan area, also called Kafiristan.

In 1895, Amir Abdul Rahman, the then King of Afghanistan, conquered Nuristan and forced the inhabitants of the area to convert to Islam. He ordered their books to be burnt. If it wasn’t for the royal family of Chitral, the Kalash would not have survived. Many fled to Chitral to avoid conversion.

There is yet another theory that the ancestors of the Kalash migrated from Tsiam, a place in South Asia. Neither theory is proven, but today less than 4,000 Kalash remain who have not been converted to Islam. Besides forced conversion, another threat to their numbers has been from polio.

TNS: To change the subject, tell us about your art pursuits while you were living in Pakistan.

MBA: I painted a 35 ft long Black Light mural in fluorescent colours at a discotheque in Karachi called Three Aces. I did the interior of this restaurant with spider-web cut-glass so the images in the small discotheque kind of doubled the visible space. This was in 1976. I then joined Sasa Advertising and worked there for two years.

From 1977 to 1989 I became involved with children in Karachi, conducting art workshops. I conducted a very large workshop for the Directorate of Education, Sindh.

I was also painting Kalash subjects, as I became more and more interested in anthropology and wanted to spread awareness about the Kalash among those children, to create tolerance and respect, irrespective of religious or ethnic affiliations. The thousands of children with whom I interacted during those 12 years are now grown-ups. I want to reach out to them to say thank you, and please sign my petition. Let’s all participate in ‘Help Preserve the Kalash’.

Later, I wandered through different countries, making a living by painting. I have visited Pakistan several times, but no art gallery here was ready to exhibit my works, due to threats, during the terrible Zia-ul-Haq years…

TNS: You had a talk at the Press Club in Karachi in April, about the plight of the Kalash. Do you think the message has gone across?

Bugi: I think all those who attended my presentation were genuinely interested to preserve the Kalash culture. It is because of the Press that the people in Pakistan know about the Kalash. I once did a presentation for Ms Benazir Bhutto. On December 21, 1993, the UN declared an International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People. I personally spoke with the Secretary General of the United Nations in 1995 about the Kalash, who are known all over the world.

TNS: You have been living for several years in The Netherlands. Have you continued to paint?

MBA: I moved there permanently in1989 and have been living in a city called Breda. It’s a cheerful and historical city that has been very inspiring for my artistic pursuits. I also give lectures on the Silk Route and the Kalash way of life. I have had over 30 exhibitions of my works across Europe, including five exhibitions in collaboration with the embassies of Pakistan in Holland and Belgium.

TNS: I had once reviewed a book titled ‘Beyond the Gorges of the Indus - Archaeology before Excavation’ written by Karl Jettmar. I learnt that rock art exists at numerous sites in Pakistan, including the Northern Areas, depicting hunting scenes, ritual practices and wild-life. As an artist with an interest in anthropology, did you also study the rock art in Pakistan, in particular the indigenous art of the Kalash?

MBA: According to Karl Jettmar, these prehistoric carvings should be assigned to the second millennium BC. There is a strong presence of those prehistoric petroglyphs in the art of the Kalash, so there is obviously a connection between their culture and other influences from the northern and eastern parts of Central Asia.

I would like to quote an excerpt from a poem by King Bashara Khan’s daughter Lakshan Bibi Kalash, which goes something like this:

Oh the blessed Kalash!

The twenty-first century promises Love,

Peace, Liberty and Freedom for all.

Let’s pray and wish this to be true,

Hold on to your traditions,

Everlasting and eternal.

Oh the blessed Kalash!