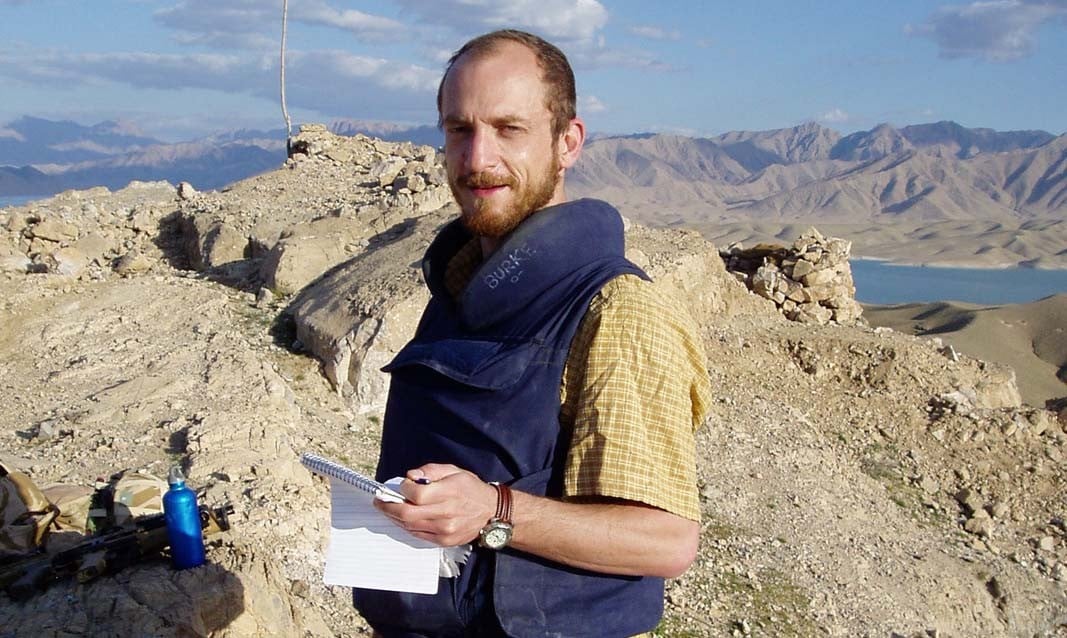

-- Interview with Jason Burke, senior foreign correspondent and writer of The New Threat from Islamic Militancy

Jason Burke is the senior foreign correspondent of The Guardian. He has nearly 20 years of experience in reporting from conflict zones in the Middle East and South Asia and has written extensively on Islamic extremism. He is also the author of Al-Qaeda, and The 9/11 Wars. His most recent book, The New Threat from Islamic Militancy, was shortlisted for The Orwell Prize in 2016. Here, he talks to The News on Sunday about the recent attacks in France and how the global community needs to come together and understand terrorism before it can be defeated.

The News on Sunday: What would you say is different about the terrorism threat that the world is facing today in the form of the Islamic State (IS)?

Jason Burke: It’s more diffuse and fragmented than ever before. For a decade or so after 9/11, you had one pre-eminent militant organisation at a global level -- al-Qaeda. Now you have IS, so that makes two already. Then you’ve got a multitude of smaller groups, many more than before, and spread in a far wider area too. You’ve also got specific situations in places like Libya, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan, Pakistan and elsewhere with their own dynamics. So it’s very, very varied, very dynamic and evolving very quickly.

TNS: In this current situation of terror, where do you place the attacks like Nice, France?

JB: The Nice attack is an outlier in a sense because it is a lone-actor attack which causes the kind of level of casualties more usually associated with a much more organised attack using many more people, often quite well-trained or conditioned by a major organisation. The Florida attack in the US is similar, though in the US you have such ready access to powerful firearms that it is easier for a single individual to cause more damage.

It’s also pretty clear that the Nice attacker only became interested in extremist ideologies just recently before killing 84 people with a truck. This may only have been a few weeks at most before the attack. The same goes for the Afghan teenager who used an axe and a knife to attack train travellers in Germany last week. The IS ideology and organisational loyalty or membership is much more accessible than al-Qaeda’s ideology. It demands absolutely nothing in terms of commitment from a potential attacker -- not even a formal pledge of allegiance or contact with a senior figure, let alone a level of knowledge of the group, its thinking or its interpretation of Islam. So we are going to see a lot of these very marginal figures who are looking for some kind of revenge or redemption for whatever reasons suddenly seeing a violent attack as a way of gaining something that they don’t have psychologically.

A critical point is that such people think they are going to be viewed as heroes by the global Muslim community, and as long as that remains the case, they will continue.

This is linked to the spread of social media and the internet of course. Over 30 years a much stronger sense of global community has developed among the world’s Muslims generally. But the belief that a local community will support and approve a violent action has still been very important. Over the last 10 years this has changed as social media etc has meant another community has become much more present in the lives of any potential attacker. There is now an alternative to the support/approval of local community for any attacker. An alternative community - specifically, the global extremist community who claim to be representing the whole ummah - can offer that support and legitimacy instead.

TNS: How do you view the rivalry between al-Qaeda and IS? Will the emergence of IS push al-Qaeda completely to the margins? How different is the appeal of both for recruits?

JB: A lot of analysts see al-Qaeda being pushed to the margins entirely. I don’t. I think actually that al-Qaeda will come back strongly in the coming years, though in a much less centralised form than before. IS is a high wire act and very brittle. It needs to continue to expand to survive. With the establishment of the so-called caliphate it has set the bar very high for success. It is now facing significant military and financial pressure. So what happens if it is no longer the biggest strongest gang in the street fight that is the Syrian civil war? How does it keep tribal support? If it can’t protect the Sunnis of western Iraq why would that community acquiesce to IS rule? If the Caliph is killed, which seems likely, can any successor really claim any kind of authority or legitimacy? If you control no major town, let alone city, then can the Caliphate be virtual? It was for nearly a century so what will have changed?

My sense is that once IS begins to be really pushed back - out of Mosul and Raqqa - it will disintegrate very quickly. It will just become a label, a brand, claimed by some groups, and often not the strong ones.

Also, if you look at how al-Qaeda affiliates in places like Yemen, the Sahel or Somalia have done, then there’s a measure of success. They have worked hard not to alienate local people and communities, and to play a long game. That is especially true in Syria with Jabhat al-Nusra, which could emerge very strongly if IS is fragmented.

TNS: You’ve talked about terrorism being very modern and contemporary in nature especially in your book, The New Threat from Islamic Militancy; what would you say is the ideal way to respond to tech savvy terrorist organisations such as the IS given the pace of globalisation?

JB: I think fundamentally you need to recognise that all terrorism is contemporary and cease to be shocked when terrorists use social media or whatever. We clearly need better international cooperation, information sharing, monitoring of financial flows and so forth. We also need media organisations - and I’m including Facebook, Twitter etc in that - to take a more responsible line on publishing violent or graphic imagery.

TNS: Given the current phenomenon of ‘leaderless jihad’ where there is an absence of a traditional hierarchy and independent actors are assuming centre stage, how safe do you think it is to label every attack that creates shock and awe as the work of IS?

JB: Well one of the big problems with this for 20 years has been the tendency to seek simple answers and to attribute everything to first al-Qaeda and now IS. Clearly, it’s more complicated than that and you need to dig deep into the local causes of any situation. There are some common themes around the world which can contribute to extremist violence, but at the end of the day all politics is local. The dynamics in Pakistan are clearly very different from those in other countries in the region, such as Bangladesh or especially Afghanistan or India, and there are even bigger differences elsewhere.

You’re also playing the terrorists’ game by turning them into global organisations. IS wants to be seen as having vast international reach. In fact, their capabilities are much more patchy. Ayman Al’Zawahiri, now leader of al-Qaeda, spoke about this years ago, saying all you need to do is wave an al-Qaeda flag somewhere and the US would spend huge amounts of money intervening. That is clearly to be avoided.

TNS: In your recent article for The Guardian, where you have outlined various causes for France being targeted time and again, among other factors, you have attributed the rise in the militant threat to the unsuccessful assimilation policy. What do you think is the point from where radicalism within a particular community turns into militancy?

JB: I think what’s often missed in this debate is the importance of conservative views - homophobia, reactionary views on the role of women, anti-Semitism, a view of the West as decadent etc. or as the US as entirely predatory - in fuelling violence. Not all the people who hold those views are violent, clearly, but all the people who commit violence hold those views, even if their own lives are full of ‘sin’. So there’s no single point at which things turn into militancy. It’s simply that the higher the broader background level of this worldview -- which is shared by political Islamists as well as the neo-traditionalist salafis etc -- the higher the number of violent individuals or networks are going to emerge.

In France, there is a particular problem because the Muslim minority have been economically marginalised, and poorly integrated in a number of areas. The demands of French secularism are pretty rigid. The more supple pragmatism of the US or UK’s multiculturalism helps a lot here I think.

TNS: The attacks in Paris and now in Nice also raise questions about the capabilities of the security structure in the country and have emphasized the need to improve. How difficult will it be for the country to ensure personal freedoms for residents in such a situation? Given France’s pledge to accept 30,000 refugees from Syria, how difficult will it be to remain unbiased in dealing with them?

JB: I’m not sure the 30,000 from Syria are really the problem here. Any security provisions are directed more against the existing population of 63 million than a relatively small number of arrivals. The French need more resources, not more powers, as is the case almost everywhere. Most of the attackers were known to the authorities. That’s a problem of manpower and management, not a lack of legal capabilities. So sensibly done, there’s no inherent reason for civil liberties to suffer.

TNS: What factors will help in countering violent extremism globally?

JB: Understanding it, and understanding that whenever we think we have actually understood it, violent extremism has evolved. One thing I think is likely is a rise in leftwing and rightwing secular terrorism in coming decades. Though Islamic militancy will continue for a very long time too, sadly.