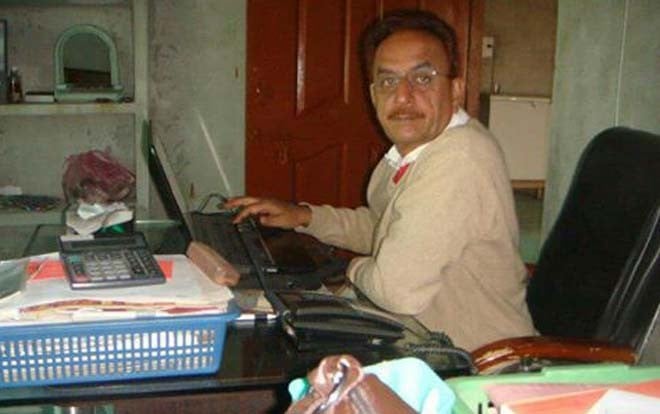

Zafar Lund raised people’s issues through theatre and activism all his life

Given the growing stifling of voices against discrimination, inequality, oppression and injustice in present-day Pakistan, the broad daylight murder of Comrade Zafar Lund at the hands of unknown terrorists was not unusual news.

Nourishing the ideals of humanism in a subdued manner may still be a pardonable offence but translating these ideals into actions and organised way of resistance becomes a crime, the punishment of which is nothing less than brutal murder by unidentified men.

After Parveen Rahman, Naeem Sabir, Rashid Rehman, Sabeen Mahmud and Khurram Zaki, comrade Zafar Lund was another such voice which was to be silenced, and was finally silenced on July 14 in Kot Addu (district Muzaffargarh).

Born and raised in Shadan Lund, a small town in district Dera Ghazi Khan, Comrade Zafar Lund got his early ideological inspiration from Marxism against the backdrop of democratic class and national struggles and rising Bhuttoism in the country in the 1970s.

In his youthful days, he started to sit, chat and work with Marxist-Seraiki ideologue Ustad Fida Hussain Gaadi, then the headmaster in Government High School, Shadan Lund, and a number of progressive nationalist figures like Salim Haidrani, Mahmood Nizami, Irshad Taunsavi, Allah Bakhsh Buzdar, Dr Ahsan Wagha and many others.

Later on, after Zia’s Martial Law, he joined Democratic Students Federation (DSF) while studying in Karachi University in the mid-1980s, and dedicated the rest of his life to the cause of the oppressed and exploited people.

I first met Comrade Zafar Lund in the last years of General Zia’s martial law at the annual Khwaja Fareed Seraiki Mela in Mehray Wala (district Rajanpur). Surrounded by a bunch of highly critical friends at a tea shop, Comrade Zafar was intensely engaged in a heated debate on class struggle and national struggle.

Sticking to their ideological guns, the proponents of both class struggle and national struggle were taking the class question and national question in an ‘either-or’ form. Whereas Comrade Zafar, with a turban of Ajrak on his head and wearing typical proletariat looks, was of the opinion that class question and national question were not mutually exclusive.

Indigestible as it was to his audience, Zafar’s point of view was bringing more and more intensity to the debate. The more he defended his position, the greater criticism he would receive in turn, forcing him to answer the sharp and pinching questions from both sides. From his facial expressions to his way of arguing, the comrade looked an aggressive young man to me, though my first impression of him didn’t last longer.

A moment later I came to know another aspect of his personality -- Zafar the artist. He had then just formed a group of Seraiki Lok Tamasha -- a theatre wing of Seraiki Lok Sanjh. He along with his theatre team was there to perform stage plays. In one of the plays, he himself performed and it was perhaps the first and last time I saw him performing on the stage though I saw many plays written and directed by him later.

It was a one-act play, performed by only two actors -- Zafar in the lead role and the other man (I do not remember his name) in support role.

It was quite a moving narration, frequently punctuated by "Ookoon Aakheen" (say to him), of the ‘pains and sorrows’ of parents whose son was away from them and how they were feeling lonely and helpless. The narration was so beautifully crafted, juxtaposing the ‘pains and sorrows’ of one family to those of other folk in his village and his Wassayb (motherland).

Zafar created such a magic with his voice that the young man, who was writing the letter, literally started crying -- tears rolling down his cheeks, and like the young man on stage, a number of people in the audience were also crying. He received a standing ovation as the play ended.

Theatre and struggle for the rights of the oppressed and exploited turned out to be his life-long passions. Using theatre as a medium to raise people’s issues in people’s voice for changing people’s lot became such an overriding romance that he left the government job in the health department, citing it as a barrier to achieve his cherished ideals.

Instead, he preferred doing some low-paid, odd jobs like selling plastic slippers on a bicycle in Shadan Lund, selling grass at a toka (grass-cutting) machine in Taunsa Shareef and doing district correspondence for a couple of English newspapers in Dera Ghazi Khan, which allowed him some space to keep raising the voices of voiceless through theatre performances.

In the late 1990s, he along with his comrades of Lok Tamasha established a civil society organisation, Hirrak Development Centre (HDC). Hirrak literally means the sound of gushing water of hill-torrent, which is heard before the water comes. It is a harbinger of hope and prosperity.

The HDC opened new horizons of activism for him. His association with the landless people and their issues deepened. The communities adversely affected by mega development projects became centre of his activity. Activities like protest demonstrations, people’s assemblies and press conferences increased manifold.

Theatre continued to be an essential source of highlighting the issues and social mobilisation but it underwent considerable qualitative changes. Children, girls, women and youth from fisher-folk and peasant communities took centre stage, replacing an erstwhile group of comrades, in identification of the themes for scripts and doing stage performances.

Zafar created new spaces for the Seraiki poets, writers, intellectuals and media persons to associate with communities, discuss the present day issues of exploitation and environmental degradation in the context of neo-liberal economic regime, and come up with new strategies of non-violent resistance.

His campaigns against corporate agriculture farming, allotment of Rakhs (common grazing lands), displacement of people by mega development projects, contract system in fisheries and environmental degradation by power projects earned him ever-increasing number of friends as well as foes.

Some windfall successes which he achieved in the resettlement of the displaced communities made him a symbol of hope among the poor and weak. Zafar became a household name among the landless peasants and fisher-folk communities, children calling him ‘Chacha Zafar’, women calling him ‘Ada Zafar’, and men calling him ‘Zafar Khan’.

People started pouring in the comrade’s house to consult him and seek his guidance on their collective as well as individual or household issues. Knocks at comrade’s door started to increase.

Open and accessible to all, he was ever ready to extend whatever support he could to the people at any hour of the day. With the same supportive spirit, he came out of his house to meet his assassins who had come under the guise of job-seekers.