The existing laws are clearly more than enough to punish those who kill for honour and a brand new law makes little sense

It was the first time the PML-N had its finger on the pulse of the nation.

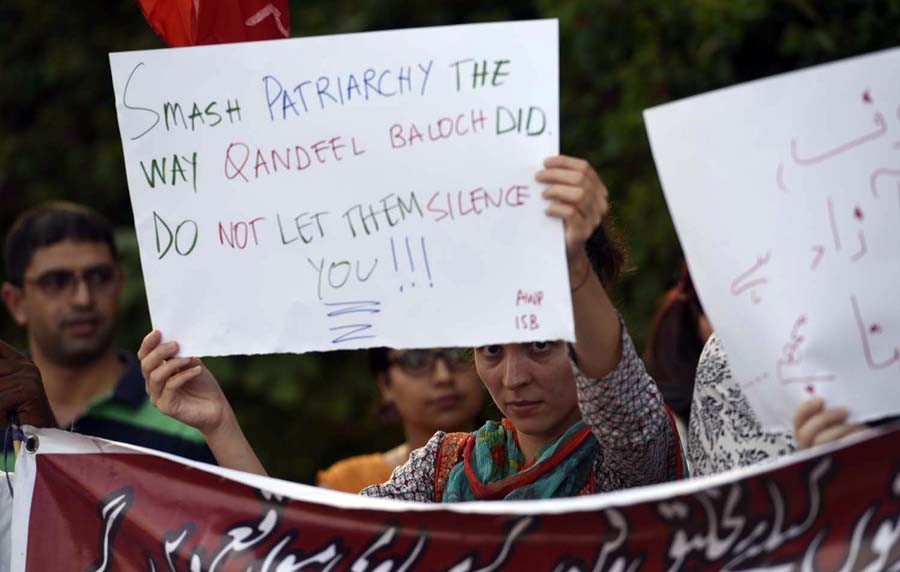

Three years of scandal, political intrigue and crisis -- never has the government said the right thing at the right time. With Qandeel Baloch’s murder, however, the government was both empathetic and responsive.

And then it betrayed a bewildering ignorance of the law and legal procedures.

To be fair, the PML-N government is not alone. When Maryam Nawaz promised a new law on honour killings, she was continuing the conversation her father had with Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy earlier this year. Screening her film for the premier, the Oscar-winning filmmaker lobbied for "new anti-honour killing laws". Rumblings from the government subsequently suggested Chinoy’s pleas would not meet the ignominious end met by PPP Senator Sughra Imam’s bill against honour killings in 2015.

Even more interesting is that the centerpiece of the PML-N’s proposed law is substantially the same as the unsuccessful bill Imam floated in 2014. Everyone wants to do away with the "loophole" that allows victims’ families to forgive the murderer and thus, get away scot free. Ostensibly to prevent this happening in Qandeel’s case, the government even took the unprecedented step of becoming a complainant in the police case against her brother. By designating the murder a crime against the state, it was argued, the government blocked her family from forgiving their son.

Except: a murder is invariably a crime against the state. Contemporary state systems -- including criminal laws -- are structured so as to preserve the state’s monopoly over violence and Pakistan is no exception to this rule. Regardless of who files the FIR, the state is invariably the prosecutor in what is deemed a crime against the state. And this is evident to everyone who’s looked at the evolution of the qisas/diyat laws.

In 1979, the Shariat Bench of the Peshawar High Court tagged the offences regarding the human body as unIslamic and after some hectic consultation, Zia promulgated laws regarding qisas (the right of the victim’s family to waive their right to retribution against the accused) and diyat (the right of the victim or her heirs to accept blood money for forgiving the accused) by end 1980. However, even this privatisation of the criminal justice system -- by providing victims with their choice of vengeance -- is a partial privatisation at best. The victim’s family can choose to forego or sell their portion of revenge; they can’t force the state to abandon its own revenge. Even if the offence is compoundable, the state always retains the right to punish the crime against itself.

Fasad-fil-arz was the term of art coined to cover the state’s right to violence and to incorporate laws regarding public disturbance. Even if the victim or her family forgave the perpetrator, the court was allowed to punish him under tazir depending on the facts of the case. In awarding ‘additional’ punishments that could extend to a maximum of a 14-year jail term, judges were to consider the past conduct of the offender; his previous convictions; the outrage to public sentiment posed by the brutal or shocking manner the offence was committed and the potential threat posed to society by the offender. But the crucial point to note is that the much vilified ‘loophole’ that allowed murderers to go scot free clearly never existed at law. If the courts deemed fit, they could hand down punishments and the forgiveness/compromise couldn’t stop them. Nobody could go free unless the courts allowed them to.

This deliberate carving out of space for the exercise of judicial discretion shows that qisas and diyat laws were never meant to have complete sway; the courts were always meant to function as the failsafe option. However, the most significant indicator of the state’s desire to retain its monopoly over violence is the fact that the federal government kept mounting appeals and review petitions against the decision to Islamise criminal law.

But in 1989, the Federal Shariat Court threw out the federal government’s appeals and demanded promulgation of Islamised criminal laws. Then President Ghulam Ishaq Khan obliged in 1990, and in 1997, Nawaz Sharif pushed these laws through the parliament largely unchanged. To this fairly expansive judicial authority, Musharraf further added specific provisions against honour killing in 2004-05. The phrase ‘honour killings’ was introduced into the law and was added to the list of judicial considerations in awarding punishments. Further, the limits of the judges’ discretion in awarding punishment under tazir were greatly expanded. The gamut of punishments available to the court was expanded to include both death and life imprisonment while the minimum term for one convicted of honour killing was set at 10 years.

This is why a brand new law makes little sense.

First, why reinvent the wheel? Forgiveness does not preclude punishment and the existing laws are clearly more than enough to the task of punishing the perpetrators of honour killings. Equally obvious is the fact that the lack of convictions for honour crimes has to do with shoddy implementation and enforcement of existing laws. Neither the state nor civil society has reminded the judiciary of its obligation to punish the crime against the state, even if the heirs choose forgiveness. How will adding more law to the books help?

Second, if the legislative object is to reduce the occurrence of honour crimes, that’s easier done by getting the courts to award harsher tazir punishments. The success of a criminal justice system rests on the inevitability of punishment. The relevance of forgiveness will fade as soon as the state begins disregarding forgiveness in its judging calculus and exercising its own right to punish offenders. Much before qisas and diyat came on the books, "grave and sudden provocation" was considered adequate mitigation for an honour crime. But its significance as a legal argument faded once the judiciary began rejecting it as a mitigating factor.

Obviously, reading down the law is a process, not an event. But asking the judiciary to adhere to the law as set out in the books is an unexceptional request and a worthwhile first step.

Finally, if the intent is for the state to regain its monopoly over prosecution and punishment, what better way to seize power than through its exercise?

There are also practical problems associated with a ‘new’ law. On the face of it, there are two ways to omit the forgiveness clause. The first would be to purge the penal code of the relevant provisions. The other option could be to have the judiciary sit in judgement over the validity of the compromise/ forgiveness. Both options, however, represent a circuitous route to the espoused legislative intent that is, preventing the exoneration of the accused.

The legislative purge, for example, would require the cobbling together of a political coalition strong enough to withstand the religious right. In the current environment, this seems a farfetched dream. This is particularly so in the face of constitutional provisions that require all laws to be brought in consonance with the Quran and Sunnah. Failure to do so would attract constitutional challenges but overturning the ‘Islamic provisions’ would require 2/3rds majority in both houses of parliament -- another non-starter.

This, of course, leaves judicial oversight of compromises/forgiveness. If the judiciary were to review the merits of each case with no thought to the fact of the compromise/forgiveness effected, how would the process be any different from the one already laid out in section 311 of the penal code? Wouldn’t the judges still be ignoring qisas/diyat settlements, evaluating the case and giving their decision? Why is a ‘new’ law required to do that which is mandated by the ‘old’?

The demons may have spoken in favour of a new law but the demons don’t always know everything. After all, there was just Brexit.