Is it time to rethink our religious culture and authority?

The faithful waited for Ramzan, a whole year, to cleanse themselves of the acquired worldliness and to raise their conduct through prayer and fasting. But, in reality, the multitude of Ramzan transmissions fed them to what Iranian sociologist, Ali Shariati, calls "the great idol of our age", i.e. motorcycle, car, mobile and more, at the altar of the new god of consumerism, a faith now common to most of humanity.

This adulation of the new god indicates that religion is subservient than dominant to this phenomenon -- as writer, philosopher and political activist, Murray Bookchin, states: "capitalism today has become a society, not only an economy".

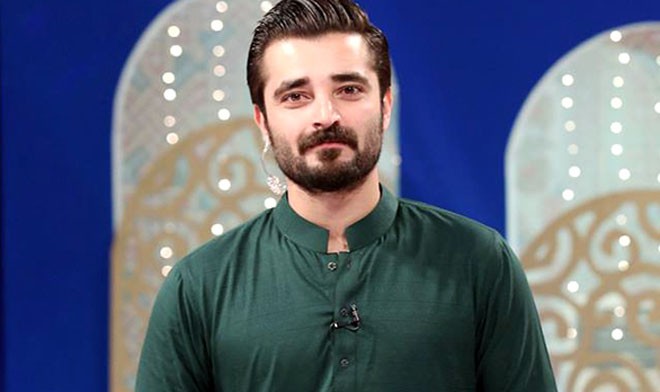

In this purview, four incidences that took place during Ramzan have been rather disturbing: First, the altercation between senator of a religio-political party, Hafiz Hamdullah, and a rights activist Marvi Sirmed, where the senator expressed misogyny in no unclear terms, even threatening the activist for being a woman; second, the Qandeel Baloch-Mufti Abdul Qavi controversy, which smacked of hypocrisy on the part of the Mufti; third, the reaction to Hamza Abbasi’s question on the publicly accepted persecution of the Ahmedi community, showing how hate has become an article of faith that life threats can be given by Allama Maulana Kokab Noorani on TV; and lastly, the murder of qawwal Amjad Sabri, purported to have been killed for content considered blasphemous allegedly by the Mullah Fazlullah-led TTP, the militant adherents of the takfiri version of Islam.

Accepting academic Olivier Roy’s argument that "religion is what you practice", can one equate our religion with hypocrisy, misogyny, hate and murder especially when all of the above stated examples involved a coterie (Hafiz, Mufti, Allama/Maulana and Mullah) that demands privilege and authority in the name of Islam? But, to answer this question, we have to assess the mainstream narrative and public opinion to understand if the above stated conduct carries religious sanctity, and whether it is accepted or condemned by society as a whole.

A broad assessment tells us that other than Amjad Sabri’s murder when hundreds of thousand participated in the funeral to condemn the act of killing and mourn his loss, the other three were controversies with a split public opinion.

But Sabri was no ordinary person, he came with a pedigree, and a shared Sunni-Shia-Sufi cultural heritage which brought together all Muslims except the takfiris. Thus, people’s reaction to his murder is not a representative case, which could allow one to argue that as a society we have moved beyond justifying murder in the name of religion.

This is further attested by a clear lack of public condemnation of Kokab Noorani’s life threat to Abbasi.

Let’s discuss where the popular stands in terms of the other three. That a popularly elected political government passed the Women’s Protection Bill while the flag bearers against the bill fit the same above coterie, suggests that misogyny is not popular. However, the coterie has support within the state structure through the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII); in politics through Imran Khan who gave credibility to the CII by stating that it would vet KP’s women protection bill before being presented to the provincial assembly; in media through the permanent presence of Orya Maqbool Jan, who can’t fathom a woman’s freedom to play cricket.

So, the sanctification of misogyny is not limited to a coterie, but has broad support among the sections of state and civil society, primarily because that coterie’s interpretation of religion is popular, and its authority over religious interpretation stands unchallenged.

Similarly, in the case of Ahmedis, the sanctification of hate is even more widespread and further includes the otherwise moderate sections of society, because the religious narrative as promoted by the coterie completely overpowers the political questions of citizenship and rights.

The hate propaganda has been so effective that the otherwise reasonable people simply refuse to acknowledge the humanity and constitutional political rights of fellow citizens. As the political simply cannot be demarcated from the theological on this issue, it creates a much wider space for the coterie’s worldview, and subordinates the state sovereignty.

This restricted state sovereignty is attested by the state’s refusal to uphold freedom of expression while curtailing hate speech, as both parties were banned in the Hamza Abbasi case. It shows that the state is either not strong or not clear enough to make a distinction, thus implicitly privileging the coterie over other citizens.

This acceptance of privilege in the name of religion further feeds into the question of hypocrisy, as the same deed when not done in the name of religion would otherwise be condemned. Thus, terrorists cloak themselves as defenders of Islam; the ultra conservatives promote misogyny as if upholding religion; the xenophobic articulate their hate cloaked as lovers of the prophet. This is only possible because both the society and state have accepted the coterie’s demand for privilege and authority in the name of religion.

A clear indication of this acceptance is the exhibition of public piety, which Sufis through the ages have equated with hypocrisy, but the state continues to uphold it through its Ehtaraam-e-Ramzan Ordinance.

The justification of hypocrisy, misogyny, hate and murder implicit in our contemporary religious practice, is an outcome of the acceptance of the coterie’s privilege and authority in the name of religion, and is kept intact through a framework of public piety. Thus a change in the ethos of our lived culture requires that public piety, privilege and authority in the name of religion, and subservience of religion’s ethical principles to consumerism are publicly challenged.

Edhi, the great humanist did exactly that through the example of his lived life, while Aziz Mian Qawal publicly voiced that same using Sufi metaphors. In Mai Sharabi (I , the Drunk), he states "Taj, takht aur hakumat nahi manta; deen o dunya ki sarwat nahi manta; meray saqi, main daulat nahi manta" (I don’t accept the crown, throne or rule; don’t accept worldly or religious benefits; my wine bearer, I don’t accept wealth), and in Yeh Hai Maiqada, Yahaan Rind Hain (This is a tavern of the Rinds), he openly challenges the coterie, "Yeh harem nahi hay aye Sheikh ji; yahaan parsai haraam hai" (Dear Sheikh, this is not a sacrosanct harem; piety is forbidden here).