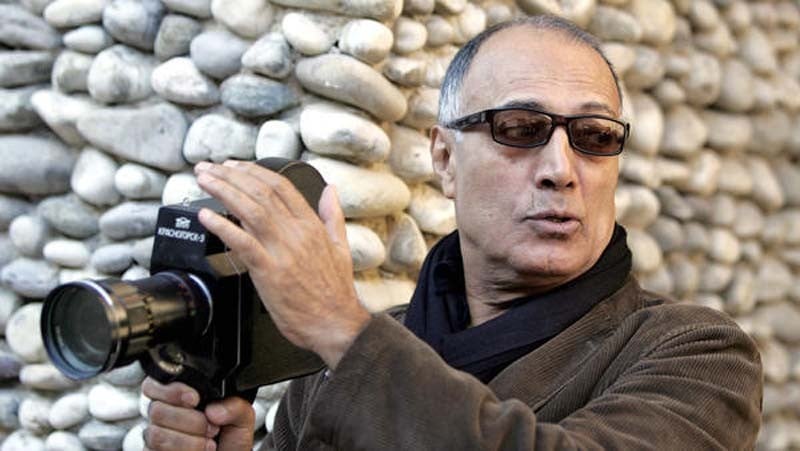

The Iranian film-maker that challenged the intellect of the viewer through his experimental works

Abbas Kiarostami, who died on July 4, 2016 at the age of 76, was arguably the most prolific and experimental of Iranian producers and directors, such as Dariush Mehrjui, Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaaf, Majid Majidi, and Jafar Panahi (in prison since 2010). When Forough Farrokhzad directed The House is Black (1963) and Dariush Mehrjui made Gaav (The Cow, 1969), a new wave in the Iranian cinema ushered in, and Kiarostami carried the torch forward with a cinematic zeal that reminded viewers of the Italian cinema in the post-WW II Europe. If Gaav was a poignant depiction of an Iranian establishment under the Shah that was too attached to its past glory, the Iran of 1980s became an even sadder theatre of a lost identity under the new theocracy.

Close-up’s release in 1990 brought Kiarostami to world fame, as it was believed to capture the essence of docufiction. Docufiction is the cinematographic combination of documentary and fiction. This genre, sometimes classified as a sub-genre of narrative film, attempts to capture reality as it is. Direct cinema and cinéma vérité are related concepts that simultaneously introduce creative elements to strengthen the representation of reality.

In docufiction, a real-time depiction is important; and to achieve this, Kiarostami used real people who were part of the actual narrative.

It was in 1989 that Kiarostami read a news story about someone impersonating the famous Iranian director, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and getting arrested when the family that had been tricked into believing it would be starring in his film reported him. Kiarostami approached the court and the family, and requested them to reenact the actual events. Both agreed, and Kiarostami shot the drama with aplomb.

There have been numerous movies based on real events, but not many have used the real people in the entire film without even a single actor. It is not a simple documentary reconstruction of the events; it is Kiarostami’s subtle approach to the narrative that makes it witty and illuminating. He explores the relationship between truth and falsehood with a particular focus on appearances and reality. The narrative uses flashbacks, as reality and acting keep shifting.

The film ultimately becomes a multilayered investigation of the status and ambiguity of truth in our lives. We understand how it is possible for an imposter not to be a conman but simply a victim of his own concocted reality.

Close-up garnered awards at film festivals in Istanbul and Montreal.

Kiarostami’s next experimental movie was Taste of Cherry in 1997 which revolves around a middle-aged man (Homayon Ershadi in his debut role) driving around the outskirts of Tehran in search of someone to either bury him in a grave he has dug for himself or rescue him. He offers lifts to different people of diverse nationalities: a Kurd, an Afghan, an Azeri who bring with them their own past, against the backdrop of fighting in Kurdistan and Afghanistan. The Kurd and the Afghan decline his proposed money in return of the favour he asks; the Azeri old man agrees but tries to talk him out of his suicide plan.

Shot mostly in minimalist fashion with a dashcam (dashboard camera) in the vehicle and a juxtaposition of longshots, the film has been interpreted as an allegory of undecidedness of the Iranian society waiting to be rescued or becoming suicidal.

Though Kiarostami did not confirm whether the suicidal man is actually a depiction of theocratic Iran torn between life and death and surrounded by the troubles in Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, and Iran itself, this film has been taken as a fine philosophical portrayal of the Iranian agony.

His next experimental film was The Wind Will Carry Us (1999). The film is set in a mountainous village in Kurdistan where a mourning ritual is about to take place after the much-anticipated death of a 100-year-old woman. A film crew has arrived to shoot the happenings but the old woman proves to be too tough for the angel of death; as the death throes prolong, the crew waits impatiently for the terminally ill woman to die, and a small boy is used as an informer about the worsening condition of the woman.

The engineer tries helplessly to communicate with his handlers in the city with very poor reception on his cell phone. Again the film is philosophical in nature and tries to show an old and rustic establishment that refuses to die, and the signal from the new civilisation are unable to reach. As the stench of death is felt, the boy represents a new generation that tries to communicate with the outsiders.

One can understand the prophetic meaning of Kiarostami’s symbolism in wake of the recent agreement between Iran and the Western powers, and the persistent condemnation of this deal by the aging clergy.

This film also received international accolades.

Other films worth mentioning are: a documentary ABC Africa (2001) about the orphans of Uganda, a minimalist film Ten (2002), and another experimental film Shirin (2008). Ten is a classic in the sense that in employs a unique idea of an entire film being shot in a car with 10 conversations filmed by dashcams. The driving lady is the same but the passengers with their unique dilemmas come and go. The 10 sequences are diverse in nature but all examine the contrasting emotional lives of various women - a prostitute, a jilted bride, and one on her way to prayer.

Shirin (2008) features more than 100 famous Iranian theatre and cinema actresses and a French star, Juliette Binoche. All we see is their faces and all we hear is the screenplay of Khosrow and Shirin, the famous Persian poem from the 12th century. All actresses are mute spectators just listening to the dialogues and looking at the stage or a screen not seen by the viewers. As the story progresses, the expressions on women’s faces change from charming to agonising, and from smiling to almost crying.

You may call Kiarostami too philosophical or too experimental but his genius and innovation cannot be disputed. He worked in a hostile environment but still was able to challenge the intellect of viewers and the establishment.