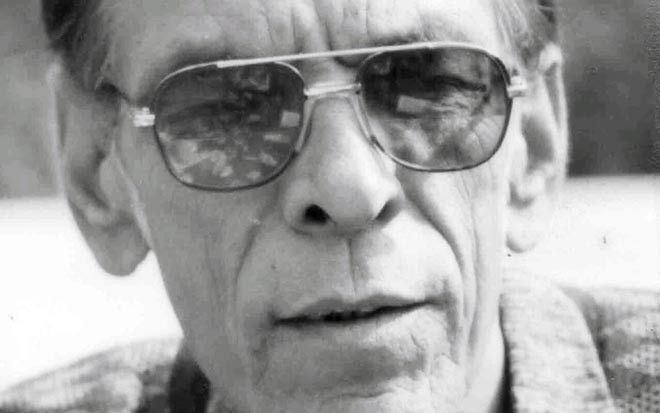

He no longer writes anything -- not even letters. He no longer reads anything -- not even letters. He exists in a state which cannot be defined. Not absent but not present either. Persistent illness has reduced him to a wreck. Perhaps in his imagination he wanders about, wander-struck, in a limbo, much like the one many of the characters in his fiction inhabit or inherit. Were he to pick up his pen again, nothing is impossible, he may tell us a few more tales in the manner he has perfected - unique for its atmosphere, limpid narrative and stunning ambiguity.

I refer to Naiyer Masud, of course, whose stories are unlike anything in Urdu fiction before he burst onto the literary scene and would be unlike anything written in the future. He is inimitable. Try to imitate him and you would come a cropper. He did translate a bit of Kafka early in his career. He may have learned a great deal from him but did not try to copy him. He assimilated Kafka, or to use a better term, metamorphosed Kafka. What Naiyer Masud has written is something indefinable, a haunted space where things are inverted, diverted and circumlocuted.

There would always be some who dislike his work for various reasons. They complain that he is too vague, too politically incorrect, oblivious, in fact, of politics, that his fiction, pointless for the most part, possesses a dream- like ambience, cut off from all social, economic and ethical moorings. Decadence in a new garb, so to say. Some, misled by his Spartan prose, think that what they are reading is a translation. Those who mount a critique on him have some justice on their side. But they forget that real talent never pays court to manageable literary sensibilities. Whoever is gifted takes the road less travelled by and that makes all the difference.

There was a time I knew nothing about Naiyer Masud. His father, Masud Hasan Rizvi Adeeb, an old-fashioned but insightful critic, an aficionado of Lucknow’s vanishing culture and an apologist for the Nawabs of Awadh, was a well-known figure. I thought that Naiyer Masud was, at best, a research scholar and would follow in the footsteps of his father. One day Ahmad Mushtaq, one of the most well-read of our poets, handed a small book, entitled Seemya to me and said: "Read these stories. You will find them very unconventional." That the author of the stories was Naiyer Masud came as a bit of a surprise but what intrigued me, as I am invariably and for no decent reason fascinated by the occult, was the book’s title. Seemya is a magical art. Its sole purpose is to create illusions which look disturbingly real to the observer.

By the time I read the first few pages I was mesmerised. I raced through the book and at the end felt completely floored. How on earth could he write so remarkably well, I wondered. The stories seemed to trail away as a whisper, apparently leaving nothing in their wake, and nonetheless were excitingly readable. I read the book again to make some sense of it and began to see the glimmerings of some sort of a plan. But was it a novel split up into stories of unequal length or stories cryptically connected to add up to a novel? I am still not sure.

As I got in touch with him and began to know him a little, I came to realise how contrived his prose actually was. On the face of it, very plain it seemed and effortless, the reader sailing across the pages without a snag, never realising how much hard work has been done to give it a certain look. Naiyer Masud, as he himself explained, removed without any remorse metaphors, figures of speeches, set phrases, in fact all the razzmatazz of an ornate and overwrought style from his narrative. What was left behind could be seen as a deceptively plain surface. By this simple exercise of methodical pruning, he offered us a prose which, although easy to read, looked singularly unfamiliar.

Matters did not come to a conclusion here either. Even the narrative was carefully examined to seek out those portions which could be safely excised. The intent was to sever the more obvious connections, as though continuity was a jig-saw puzzle with some of the pieces hidden away. You would think that such cuts were likely to disrupt or unhinge the narrative. It is here that Naiyer Masud’s mastery makes its mark. The crevices are there but not visible or only dimly conceived. It is enough to get the reader baffled. Nothing seems to be missing and yet he is seized by misgivings that there are more meanings lurking in the narrative and he must grope for them in the dark. No desire for compromises, not in Naiyer Masud’s book at least. What a fine filmmaker he could have been. Another Tarkovsky maybe.

Probably riled by the criticism that his fiction was no better than private fantasies imposed on an unsuspecting public, he also wrote a number of stories in a realistic mode, often with endings that seem inconclusive. In a sense they are more real than most realistic fiction, because life itself is largely an inconclusive affair. The best of the lot is ‘Noshdaru’ (a sort of elixir or panacea), the story of two very old apothecaries, one a Muslim, the maestro, the other a Hindu, his disciple. These old men, in their 90s and 80s, are the epitome of devotedness, fully aware of the values of their profession, no longer in vogue, are touching in the extreme. It is the most delicately-rendered account of senility and obsolescence in Urdu.

The other story which must be mentioned is ‘Taoos Chaman Ki Maina’, now famous for two reasons: its vivid realism and the way it provides a glimpse of the old and independent Lucknow, before it was seized by the British. It reveals how deep a sense of history Naiyer Masud possesses and how charmingly he has moulded it into fiction. The ending, however, is disappointing and no matter what Naiyer Masud says to justify himself, the fact is that he did miss a trick in this instance. He should have made a novel out of it.