A historical record of the Pakistani Left by none other than one of the oldest comrades Abid Hassan Minto

Commitment is considered a virtue in social and political life. However, it should not be considered as the sole factor to judge a political being. The dictionary defines the word commitment as the state or quality of being dedicated to a cause or activity. But in the same entry it is also described as an engagement or obligation that restricts freedom of action. In many ways, commitment restricted freedom of thought in ideological formations and that area needs some attention.

Even at the age of 85, Abid Hassan Minto remains committed to progressive ideas. Much like the 92-year-old Zafar Ullah Poshni, 90-year-old Abdul Rauf Malik, 88-year-old Eric Rahim, and 88-year-old Tufail Abbas, Minto sahib is among the senior-most group of comrades who are still not ready to give up. Even if you disagree with their politics, ideas, or lifestyle, their resilience must be acknowledged.

After a 68-year-long political career, Minto is close to retirement and has told his comrades that he will not contest for the Awami Workers Party’s (AWP) presidency in the upcoming election.

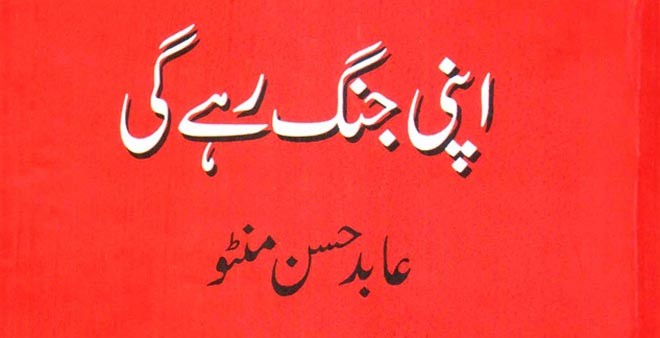

The book under review, Apni Jang Rahay Gi, is a compilation of articles, speeches, resolutions and interviews of Minto, who is a committed spokesman of the Pakistani Left. Since his autobiography is expected in the near future, this compilation can be considered as a starter.

The book can be understood as a historical record of activities of a section of the Pakistani Left since 1972. As it contains commentary on events that occurred before 1972, so you can read glimpses of post-1947 Left politics as well. Unfortunately, it has no index and this compromises its value in many ways.

The book starts with a detailed 23-page introduction which was penned in May 2016, and this is the only current essay in the compilation. The introduction allows the reader to understand the thought process and ideological narrative of the author. It mentions two major communist centres in Pakistan’s early days and criticises some recently published books about Leftist politics which discuss Leftist activities in Karachi but deliberately leave out Lahore. As Minto was among the young members of the Communist Party of West Pakistan (CPP), he has first-hand knowledge of the party’s workings. He claims that Azad Pakistan Party of Mian Iftikharuddin was the first open front of CPP and this needs attention.

In the introductory essay, Minto mentions a recent book Fareb-e-Natamaam written by Juma Khan Sufi, a Pukhtoon communist, that exposed the subversive activities of nationalists and a Karachi-based communist group during the first-elected government of Pakistan from 1972-1977. It is high time to review the alliance of communists and nationalists, Sufi paved the way for rethinking this. When the National Awami Party (NAP) was formed, a convention was organised at Dhaka in 1957 -- it was well attended by the Left nationalist forces of East and West Pakistan. They organised a public meeting at the historic Paltan Ground in Dhaka which was sabotaged by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his goons. In this essay, Minto also talks about the bad politics of the powerful Khans from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa who were elected in the West Pakistan assembly under NAP tickets.

In his introduction Minto does not mention the left extremism of February 1948, nor does he highlight the Progressive Writers Association’s (PWA) infamous resolution of 1949. However, in another part of the book, Minto mentions and criticises Ranadive Line but in P. C. Joshi style. When the Indian Bengali communist Mohit Sen wrote his excellent autobiography, A Traveller and the Road, he wrote about Moscow. But Minto omits the dictations that Moscow issued in making and breaking the Ranadive Line in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Although Minto was a member of PWA, in one of the essays (P 376) he boldly criticises the Association’s infamous 1949 resolutions and links them with the extremist line of B. T. Ranadive -- the last secretary general of united communist party of subcontinent and the first secretary general of the Communist Party of Bharat from 1948-1952.

As Minto is a constitutional expert, the book comprises interesting constitutional debates and a critique of civil-military relations. Towards the middle of the book, Minto writes about the background of Article 3 of 1973 constitution. He describes that the Article was derived from ‘Socialism’, a chapter from Anti-Dühring written by Friedrich Engels, a friend of Karl Marx.

The book also comprises a long but interesting interview of Minto by Suhail Warraich in which Minto unsuccessfully defends Musharraf’s infamous NAB law. But here Minto sahib also mentions his displeasure with the Musharaff government for contesting two cases against Benazir Bhutto and Zardari.

During the interview, Minto accepts the failures of the Left, not only in Pakistan but also at the international level; but when asked to comment on his own rift with his ideologue C. R. Aslam, he fails to rationalise the split. At this point, however, he tells Warraich that socialist change must come through democratic means. He is a firm advocate of a democratic system in which people have the right to vote on the basis of adult franchise and the elected tier has supremacy. He says that we are not ready to accept any other form of democracy. Left needs this vision which was largely missing in previous leaderships and Minto mentions it too in the book.

In many ways Minto is advocating participatory democracy and wishes to include representatives of underprivileged classes in assemblies. He is a supporter of a separate constitutional court and maintains that the "parliament must have a role in the appointment of judges".

There is no doubt that the Left in Pakistan needs a new narrative but without revisiting the history of Left politics, how can we find the way forward? We have a very weak archival record so it is important that we first build it. Minto book is a welcome addition to this record but a majority of workers on the left are still silent. Without their involvement and contribution to the Left literature, we cannot build a good resource.