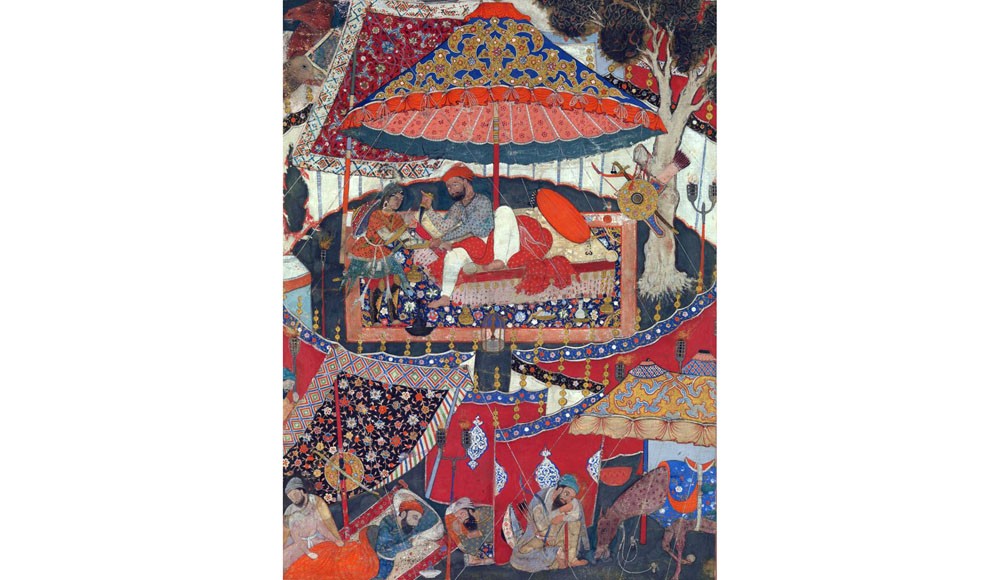

An interesting subplot that tells a lot about the durbari politics of the time

Buzurgmehr and Bakhtak are two advisers to the King of Persia, first Kekobad and then his successor Kekhusrow, Khusrau or more famously known as Nausherwan. The tale has been told in such a way that Buzurgmehr appears to be advising for the good, not only of the King but also to his nemesis and future rightful victor leading the Lashkar-e Islam, Amir Hamza bin Abdul Muttalib.

The historical reign of these two kings of Persia falls in the fifth and sixth centuries AD, i.e. just before and during the advent of Islam in the Arabian peninsula. According to historically distorted time of the Dastan-e Amir Hamza, in the words of one of the writers of the printed volumes, Hamza and his comrades are ‘natural’ Muslims, even before the religion is proclaimed. All the wars and conquests of the fictional Hamza take place in an ahistorical time before the real, Islamic conquests, including that of Persia. This has been done to achieve the willing suspension of disbelief on the part of the listener/reader or to enable the reteller/scribe to claim plausible deniability, depending on your point of view or preference.

In fact, the retelling of old stories is always to some extent informed by contemporary concerns. The tale, invented about the two kings of Persia and the fictional conquest of their land and people by the imaginary pre-Islam Islamic hero, has been retold again and again in different parts of the world invaded and conquered by Muslim warriors and inhabited by Muslims. The version worked upon by the South Asian scribes is claimed to have been written in the durbar, and on the orders of Mahmud Ghaznavi.

Read also: Selling a worldview

What did the rewriters of the Dastan in Mahmud’s durbar and the durbars of Oudh, Rampur or Agra seek to achieve, in what way did they mould elements of the old fictional material into new forms, and in what manner did they want to serve their contemporary rulers for their own personal benefit? These questions are not dealt with in detail by Najm Hosein Syed in his essay. Instead, he focuses on the Punjabi verse version of Dastan-e Amir Hamza penned by Maulvi Ghulam Rasool and tries to find traces of the events of recorded history and their treatment in its text, and their possible connections to the events during the lifetime of Maulvi Sahib.

One interesting aspect of the tale is the central role played by Buzurgmehr in the fictional events that take place in the story. In most cases the King Kobad gives more weight to the evil Bakhtak’s advice, which invariably, and understandably, results in trouble for the kingdom. However, there are two prominent occasions when Buzurgmehr makes the vital decisions that keep the kingdom and the story going in the right direction. Kobad comes to know that a child is about to be born in Mecca who, once grown up, would defeat Nausherwan, the king’s son and successor. Kobad dispatches Buzurgmehr to Mecca with the orders to abort all the pregnancies in that area, in order to stop Hamza from coming to the world. Buzurgmehr duly goes to Mecca but, instead of carrying out his employer’s orders, blesses the birth of Hamza and makes him his own godson. (Hamza’s colourful comrade the Umru Ayyar is also born at precisely the same day, in Mecca itself, but, keeping with his station in the hierarchy, to a slave family.)

Read also: Hamza’s stories

Buzurgmehr is still at Mecca when King Kekobad passes away and his son Nausherwan becomes the new king. On the evil advice of Bakhtak - i.e. Buzurgmehr’s durbari rival - Nausherwan doubles the taxes on farmers’ land and its produce. When Buzurgmehr returns from Mecca, after doing the needful there, the new King comes, bringing Bakhtak along, to a distance in order to receive the senior adviser. While returning to the capital of the kingdom, the three of them hear some birds wailing and quarrelling amongst themselves. Bakhtak suggests that Nausherwan ask Buzurgmehr to explain what the birds are quarrelling about as the latter is supposed to know the animals’ tongue.

The kings orders Buzurgmehr to explain what the fuss is about. Buzurgmehr obliges

The animals quarrelling amongst themselves were owls who need hamlets turned into wilderness for their abode. One of them wants the other to give 14 ruined towns to finalise a deal. The other owl claims that as long as Nausherwan is the King of the land, there would no dearth of ruined towns.

Read also: The amir and the alim

Hearing which, Nausherwan shifts the blame, naturally, to the evil Bakhtak. Buzurgmehr, quite as naturally takes the matter in his own hands, and takes all the credit as well.

So, all the corrective measures of reducing the taxes, making the economy prosper, and establishing peace all around have been credited to the wise and righteous Buzurgmehr, although these measures result in the goodwill of the king who obtains the title Adil or Just.

Bakhtak had conspired against Buzurgmehr, but not only did the latter’s wisdom defeat his evil design but put the country’s economy and polity back on track. His measures of reducing taxes and lagaan made the subjects prosper. Everywhere there was peace and justice, and so on. It is in this way that the Alim - thanks to his monopoly of written word - outwits and outlives his rivals in the durbar. Whatever the main events of the story, this interesting subplot can tell us a lot not only about the durbari politics of the time of the imaginary story but also the politics of the time when the story is being retold.

This is the fourth part of a fortnightly series on the subject