Through his work, the playwright and actor dispelled the belief that theatre could not be adopted as a viable profession

Kamal Ahmed Rizvi was basically a theatre person, though he wrote a lot, not necessarily for the stage, and had many friends among the painters.

He was, thus, totally cued into the artistic community and was an insider about art, theatre and literature in the early years after the Partition.

He migrated to Pakistan from Gaya in Bihar in the early 1950s, had no home, no profession, no family in the beginning; but what he had was wit, tenacity and the will to survive. This he put to great advantage in those years, and this kept him afloat till he was recognised and had enough to lead a fairly comfortable life -- all disclosed in his posthumous publication Kamal Ki Batain.

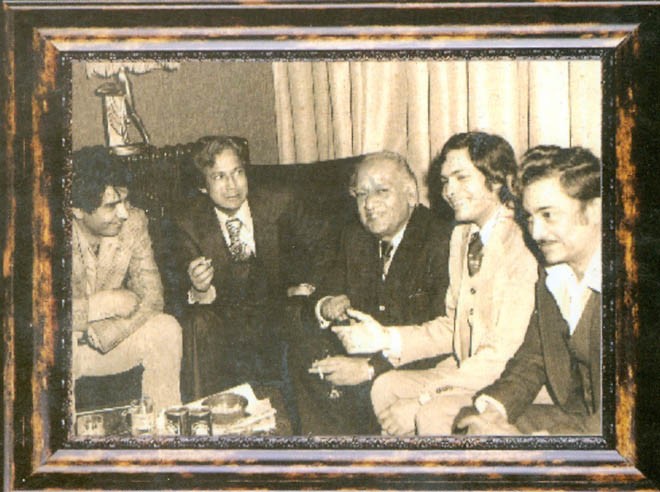

He worked on the radio and edited journals like Shama, Aaina and Tehzeeb, translated many European and American classics including plays. Like all youngsters, he wanted to meet Faiz Ahmed Faiz who at that time was the editor of The Pakistan Times. He barged into his office once and engaged him in a conversation. Faiz, in his usual low-key style, listened to him patiently. Rizvi was very impressed by the unassuming attitude of the great poet and started considering him his friend.

When Faiz was appointed the secretary of the Pakistan Arts Council, Alhamra after he was released from jail for the second time in 1959, the Arts Council found a purpose which may have been there embedded in its foundation documents but was not put in practice. Kamal Ahmed Rizvi, knowing Faiz, went to him with a proposition to start regular theatre in the Council because he wanted to be a professional theatre person making a living out of it. Faiz was skeptical and perhaps disapproving, not thoroughly convinced that theatre could be a source of livelihood. But he approved the proposal of Rizvi to adapt and stage Manto’s Badshahat Ka Khatma.

Faiz actually wanted to start his stint at the Council with a conference on Manto. It was to consist of a paper and afsanas (short stories). Ijaz Hussain Batalvi was asked to read a paper on Manto and it was to be decided as to who were to read the stories. Kamal Ahmed Rizvi insisted that there ought to be a play. With the help of Safdar Mir, a script was adapted by Rizvi for the stage in which he played the leading role of Man Mohan. In this two-actor cast, the other role was played by Zakia Sarwar. The play did better than was expected: especially well-received at the critical level. That convinced Kamal Ahmed Rizvi that theatre could be seriously considered as a viable proposition.

Faiz, though inwardly pleased, was not convinced and wanted theatre to be an activity on the margins because it failed to generate a consistent source of income.

It was also a sort of rehabilitation of Manto. He had been greatly reviled and demonised by both the right and the left because of his fearlessly independent stance. He was seen as a threat to the middle classes’ respectability, a non-conformist where political ideology was concerned. He did not tow the line of writers saluting those in power, was sent to jail, declared a lunatic and attacked all around. But even a few years after his death, it still needed courage to have him staged and talked about in a positive light.

Kamal Ahmed Rizvi who was also a regular at the Pak Tea House had gotten to know Manto and shared many a session with him as a young aspiring writer. Manto had no money while he had to produce stories on a regular basis to make two ends meet. At times, the stories were mediocre and as Manto himself confessed he was not a machine that could churn out quality stories regularly. He had to wait for the "right moment" for the story to take form but the urgency of his circumstances did not allow him the luxury of waiting for that right moment.

Kamal Ahmed Rizvi’s initiation into theatre began when he was cast in Zia Mohyeddin’s Julius Caesar held at the Open Air Theatre of Government College. The play was translated by another maverick Hafeez Javed. Alhamra held a few art exhibitions, and there was some thespian activity at the Alhamra by Imtiaz Ali Taj, Safdar Mir, Ali Ahmed, Izhar Kazmi, Rafi Peerzada and Mehr Nigar but this sporadic activity was given some regularity by the appointment of Faiz. After Badshahat Ka Khatma, Rizvi convinced Faiz to stage one play in two months as a regular event. Saye, the adaptation of Patrick Hamilton’s Gas Light with the cast of Khurshid Shahid, Shoaib Hashmi and Enver Sajjad and a budget of Rs250 was staged next. Ticketed at Rs5, the play barely ran for fifteen days. Next, Rizvi adapted Somerset Maugham’s Sacred Flame as Sheeshon Ka Maseeha but the cast had a few female roles, and other than Salima Faiz and Yasmin Imtiaz, no girl was willing to act.

Film actresses Begum Parveen and Kafira were booked after a great deal of effort. But, after the first rehearsal Kafira failed to show up and the play faced endless delays. Faiz again called Kamal Ahmed Rizvi telling him to give it all up as he also asked Sibte Hasan, who made Rizvi the editor of Bachon Ki Dunya at the Ferozsons, a job that he did for a few months.

Faiz got the Lenin Peace Prize, and leaving the Arts Council after a very fruitful stint, went to Moscow and later stayed for some time in Britain. The Arts Council was taken over by the younger lot, the contemporaries of Rizvi. While he was doing Intizar Husain’s Khawaboan Ka Musafir at the Alhamra, backstage Aslam Azhar had invited him to work for television. With another source of income, his resolve was actually fortified and he went on to do the impossible -- that is, making a profession out of theatre in Pakistan.