Casting a fresh look at the only anthology of female Punjabi fiction writers ever published in Pakistan

Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Adichie in her Ted Talk so eloquently elaborates ‘The Danger of a Single Story’. While quoting her initial interaction with her American roommate during her first ever visit abroad, she states: "What stuck me was this: She had felt sorry for me even before she saw me. Her default position towards me, as an African, was a kind of patronising, well-meaning pity. My roommate had a single story of Africa. In this single story, there was no possibility of Africans being similar to her in any way".

She further adds: "After I had spent some years in the US, I came to understand my roommate’s reaction. If I was not born in Africa and if all I knew about Africa were from popular images, I too would think that Africans are people unable to speak for themselves who are waiting to be saved by a kind, white foreigner".

Now, in above paragraphs, replace Chimamanda with a Punjabi speaker and her American roommate with an Urdu-or English-speaking Pakistani and read it again. If you are a Punjabi language activist, you will instantly recognise the heat and hate of that kind of patronising white foreigner’s colonial pity thrown at you by none other than the self-hating, fellow Punjabi-Urdu intelligentsia who knows nothing about the depth and splendour of the Punjab, its language, literature and culture. They have a single story of the Punjab and Punjabis: Jaangli, Jahil, Paindo who are unable to write in their own language and who are waiting to be saved by a kind Urdu/English speaking ‘foreigner’.

Raja Rasalu (1927 - 2007) rejected that single story of the Punjab all his life. He was born as Muhammad Sadiq but liked to be called by the name of Sialkot’s legendary son Puran Bhagat’s iconic younger brother. He worked tirelessly for the cause of Punjabi language, starting his endeavour with Punjabi Majlis, established by late Safdar Mir in 1957 that was banned within a year by the Martial Law bully, Ayub Khan, and then moved on to Majlis Shah Hussain, Punjabi Adabi Sangat and Punjabi Adabi Board (PAB). At the time of his death, he was serving as the Board’s secretary.

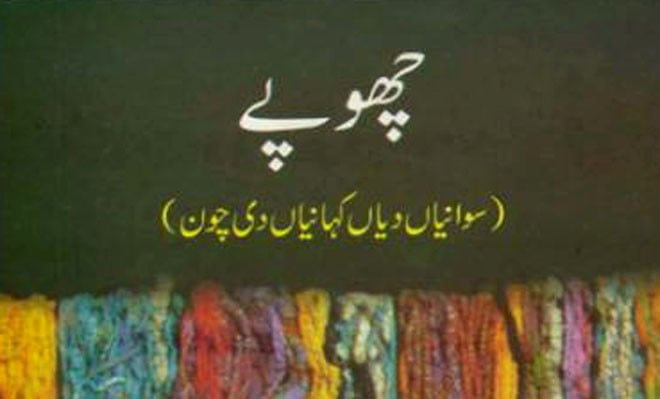

Chopay is the only anthology of female Punjabi fiction writers ever published in Pakistani Punjab. There are 26 writers included in this collection. The most striking aspect of this book is that Raja Rasalu made a conscious effort to include Punjabi short stories written in all major dialects of our mother tongue from Maajhi, Saraiki to Ĉhaĉhi.

Chopay in Punjabi tradition signifies an end to end cultural activity like Trinjan (a large spinning party of girls). Chopay are cotton rolls placed together in a specific shape. Punjabi women used to go in groups during night time to place these cotton rolls in respective baskets at their daily gathering place, so these can be used for spinning the very next morning when they hold their Trinjan. It’s a collective act of artistic production and eternal sense of community. Even the name of this anthology speaks loudly of its significance and symbolism in today’s Punjabi world. Raja Rasalu derived this name from Mian Muhammad Baksh’s verse: ‘Sada nahi hath mehndi ranggay, sada nah chañkañ wanggaN /sada nah chopay paa Muhammad, rall mill bahña sanggaN’.

Rasalu didn’t write any introductory note, details of his selection criteria or literary profiles of these short story writers. I am also not sure if the included short stories of Sindhi writer Mahtab Mahboob and Hindko writer Zaitoon Bano are original texts or their Punjabi versions. Then a few of the prominent Punjabi female fiction writers like Rasheeda Salim Seemi, Nazar Fatima, Satnam Mahmood and Kahkshan Malik are not part of this collection either and there are no explanations given. Though, it does include heavy weights like Afzal Tauseef, Farkhanda Lodhi, Riffat, Azra Waqar and Musarrat Kalanchvi.

Shagufta Nazli’s Jithay meri man aakhay, Parveen Malik’s Budhi MochiaNi and Zohra Anjum’s Aatay day deeway are stories worth mentioning. However, the overall standard of short stories included in this collection is not encouraging. Technique, treatment and thematic landscape are quite clichéd and limited. We can’t just blame writers or editors for these shortcomings. When a language is not allowed to be part of the educational system and common people are deprived access and exposure to their literature by entire state apparatus, this is bound to happen. Foreign languages are shamelessly patronised while local languages are demonised. As a consequence, both the quantity and quality of the creative production in these languages suffer.

This situation can only improve if the working class starts owning their mother tongue wholeheartedly and the state is forced through street movements to acknowledge the rightful place, importance and respect for people’s languages and cultures.

The PAB published this anthology a year after the death of Raja Rasalu in 2008. PAB is the largest publisher of Punjabi books in Pakistan and there are hundreds of treasured volumes to its credit. The Board accomplished all that with meagre financial and limited human resources, spearheaded for decades by the legend named Asif Khan (1929-2000). Being the premier Punjabi literary institution, it is high time for PAB to realise the huge potential among students and professionals who want to explore their literary heritage and identity. In this age of social media, one doesn’t need huge finances for every literary initiative. The Board needs to connect with educational institutions, school libraries and volunteer organisations through private-public partnerships even for its own growth. It needs to be aggressive in responding and adjusting to the new socio-literary realities and trends so it can inspire new readers and writers.

Like many other Punjabi books, Chopay too has number of proofreading errors showing the declining standards of our publishers and editors. The Punjabi written in Farsi Lippi (Indo-Persian script) needs extra care during typing and printing. It’s also mandatory to use ahrabs (Zair, zabbar, paish, shadd etc.) almost extensively during Punjabi typing to make it an easy and accurate reading experience. Punjabi editors and writers need to take extra pains if they want their writing to be properly read and understood.

Chopay has a unique place in Punjabi publishing history in Pakistan and an updated version of this anthology is deservingly due that should include not only those missing names mentioned above but also our post-2000 generation of female Punjabi writers.