Disputes continue over the interpretation and duration of the Durand Line agreement

Such is the depth of mistrust between Afghanistan and Pakistan that their governments use different names while referring to their long and porous 2,500 kilometres long border.

Afghanistan calls it the Durand Line after the British diplomat Sir Mortimer Durand who oversaw its demarcation following a treaty between him and the Afghan ruler Amir Abdur Rahman in 1893.

For the Afghans, it isn’t really an international border as it was imposed on Amir Abdur Rahman and arbitrarily drawn by the British when the Afghan state was weak. Successive Afghan governments have been refusing to formally recognise it as an international border and arguing that the issue is unresolved.

Pakistan refers to it simply as the Pak-Afghan border. The terminology makes it clear that it is an established international border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. As far as Pakistan is concerned, it is a settled issue.

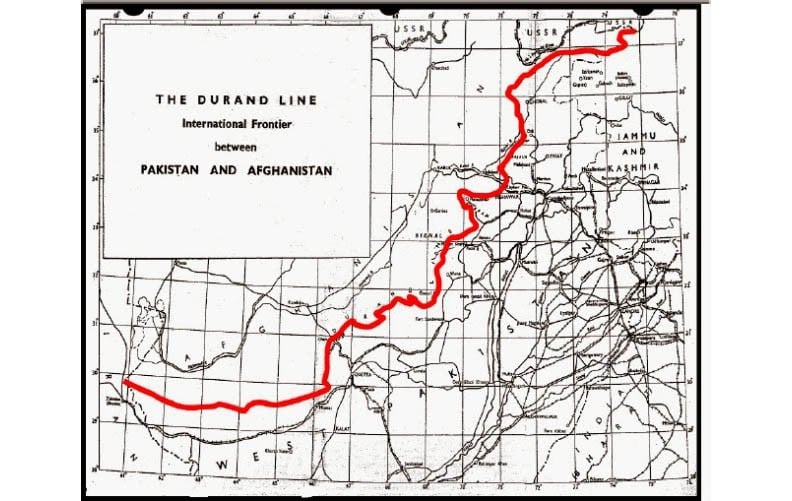

The Durand Line agreement led to delineation of the border running from the Karakoram Range in the northeast to the south through the perennially snowcapped Spinghar mountain range. The frontier extended to the Toba Kakar mountain range, separating Balochistan from Afghanistan and to the Chagai hills on the border with Iran. The Durand Line roughly follows the watershed, dividing the Pakhtun tribes and their villages.

As a result of the Durand Line agreement, Afghanistan gave up its claims over certain Pakhtun tribal lands and parts of Balochistan. It also agreed to a thin strip of Afghanistan known as Wakhan to link it with China and separate it from the Russian empire as the British imperialist rulers of India were wary of the Czarists advances in Central Asia.

The Durand Line was the cause of disputes between Afghanistan and Great Britain and prompted the third Afghan war in 1919. Since Pakistan’s independence in 1947, it has been the reason for unfriendly relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan. In fact, Afghanistan was the only country in the world to oppose Pakistan’s membership in the United Nations in 1947 due to its refusal to recognise the Durand Line and on account of its support to Pakhtunistan based on its claim that the ethnic Pashtun and Baloch ought to be given the right of self-determination whether they want to have an independent state or join Pakistan.

Read also: The other view

Though Afghan governments reaffirmed the Durand Line agreement by making additional treaties with the British in 1905, 1919, 1921 and 1930, Kabul has been claiming that these were signed under duress. In particular, the 1919 treaty signed in Rawalpindi ended the Third Anglo-Afghan War and upheld the Durand Line agreement.

Afghanistan has raised disputes over the interpretation and duration of the Durand Line agreement. The original agreement was one-page long and written in English with copies in Pashto and Dari. Mortimer Durand insisted the English copy would be the definite one, but the Afghans argue that Amir Abdur Rahman didn’t understand English.

Another misinterpretation of the Durand Line agreement is the widely held belief in Afghanistan and also by some in Pakistan that the treaty with Great Britain was for 100 years only and then the territory given up by Kabul would be returned to it. However, no expert has been able to find any reference to a specific period of 100 years in the official treaty. Afghan governments in the past have been claiming, again without any evidence, that the Dari and Pashto language copies of the Durand Line agreement have specifically mentioned the 100 years period, but it was left out from the English version by Mortimer Durand.

The Afghan government has yet to produce evidence to back its claim. In fact, it is argued that Afghanistan has refrained from taking this issue to the UN, the International Court of Justice or any other world forum because of the weakness of its legal case.

Yet another issue that is misinterpreted regarding the Durand Line is the "easement rights" granted to the tribes living close to the border and affected by some of the restrictions placed on their movement across the Pak-Afghan border. There is no specific mention of these "easement rights" but traditionally the people divided by the Durand Line close to the border have enjoyed free movement across the Pak-Afghan by simply producing a ‘rahdari’ (permit) issued to them for identification purposes.

The Pakistani authorities as part of their border management measures have now decided to stop the misuse of the permit system and allow "easement rights" to the divided tribes to travel up to 20 kilometres in Pakistan for attending social functions, such as deaths, weddings, etc, of relatives. This is causing some resentment on both sides of the border.

Pakistan inherited the Durand Line as one of the successor states to British India, but Afghanistan refused its legality. Rather, in July 1948 Kabul announced that it didn’t recognise "the imaginary Durand nor any similar line." It named a few busy squares in Kabul and Jalalabad as Pakhtunistan and began celebrating Pakhtunistan Day in presence of Pakistani Pakhtun and Baloch dissidents by hoisting the flag of Pakhtunistan and singing patriotic songs.

Pakistan responded in kind by hosting Afghan dissidents. When Zulfikar Ali Bhutto came into power in the early 1970s, he began harbouring Afghans belonging to Islamic parties and imparting them military training to counter Kabul’s support for Pakistani tribesmen and Pakhtun and Baloch political workers and fighters who had sought refuge in Afghanistan. This practice continues to this day as armed opponents of the governments in Islamabad and Kabul are still able to find sanctuaries in the two countries.

The Durand Line has been a major plank of Afghanistan’s foreign policy toward Pakistan over the past 68 years and it would continue to define their often uneasy relations until it could be resolved.