Overcoming distrust remains an insurmountable challenge and a major hurdle to normalising Pak-Afghan relations

Afghanistan and Pakistan mostly had a troubled relationship since the latter’s independence from British rule in 1947 and the ongoing phase of deterioration of their ties due to the clashes between their forces at the Torkham border in mid-June is nothing new.

There have been border clashes and casualties in the recent past as well at places like Gursal, Qamar Din Karez, Angoor Adda, Ghulam Khan, etc. Besides, the US-led Nato forces have used Afghanistan’s soil to launch attacks in Pakistan. These included the airstrikes on Pakistan’s border post at Salala in Mohmand Agency in November 2011, killing 24 soldiers and the recent drone strike in Naushki district in Balochistan that killed Afghan Taliban supreme leader Mulla Akhtar Mohammad Mansoor. Pakistan lodged protest both with the US and the Afghan government after strikes by aircraft that flew from Afghanistan.

Though the sympathies of the United States of America have been with Afghanistan in its disputes with Pakistan all these years, it looks like the Americans are moving to firmly put their weight behind the Afghan government in future. The US drone attack that killed Mansoor made the Afghan government happy as it had been demanding such strikes in Pakistan to target suspected hideouts of Afghan Taliban and Haqqani network militants.

With the US threatening to carry out more such airstrikes in Pakistan, there is likelihood of escalation in tension and the drawing of battle lines with Kabul and Washington in one camp and Pakistan in another.

India, too, has become heavily involved in the Afghan conflict by openly siding with Kabul against Islamabad and using the Afghanistan’s soil to destabilise Pakistan. The encouragement by the US for India to play a greater role in Afghanistan and the growing friendship between New Delhi and Washington has changed the equation and made a proxy war between the two old South Asian rivals in the Afghan war theatre a certainty.

Islamabad’s repeated demand for action against Pakistani militants based in Afghanistan often fell on deaf ears in Kabul and Washington. Hosting Pakistani militants was no doubt a tit-for-tat response by Kabul to put pressure on Islamabad to initiate action against the Pakistan-based Afghan Taliban and Haqqani network leadership, but Pakistan didn’t get the kind of response that Afghanistan was getting at international forums on the issue of safe havens in the two countries.

Read also: 1979 onwards

The clashes at the Torkham border didn’t happen all at once. There is a background to the rise in tension on this busy border. Pakistan was increasingly showing concern over the presence of the Pakistani Taliban in Afghanistan and their freedom of movement and the misuse of Afghan soil to launch cross-border attacks and undertake acts of terrorism in its cities.

When interrogation of the detained facilitators of the attacks on the Army Public School, PAF Base Badaber and the Bacha Khan University Charsadda revealed that the attackers came from Afghanistan via the official and busiest border crossing at Torkham, Pakistan started implementing its long overdue border management plans from Torkham in June.

The Afghans resisted the fencing of the border area and the re-installation of the gate at Torkham that had been there until 2004 and had been dismantled by Pakistani authorities when the Pakistan-funded Torkham-Jalalabad road was being built.

Earlier in May, the Afghan border force personnel had cocked their guns at the Pakistani workers and soldiers doing the fencing work, but in June they began firing to stop the installation of the gate. Both sides suffered casualties in the subsequent exchange of light and heavy fire for three days. Pakistan shut down the border for six days, mostly affecting Afghans and stopping trade activities that resulted in hike in prices in Afghanistan due to its dependence on Pakistani products.

Read also: Editorial

Though calm has now been restored and the Torkham border reopened, albeit with stricter Pakistani border controls denying entry to Afghans without visa, the bitter memories of the clashes and the human and material losses won’t go away easily.

Other factors have also contributed to the deterioration in relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan. One was Islamabad’s refusal to extend the stay of the 1.6 million registered Afghan refugees by another three years as demanded by Afghanistan on the expiry of the previous three-year agreement in December 2015 and its efforts to repatriate the more than one million unregistered Afghan refugees.

Another cause of anger in Kabul was Islamabad’s refusal to take action against the Pakistan-based Afghan Taliban and Haqqani network leaders who have turned down Afghan government’s offers of peace talks. Islamabad’s argument that it didn’t want to bring the Afghan conflict to Pakistan by taking action against the Afghan Taliban in its territory obviously couldn’t find favour in Kabul, which saw it as an attempt to protect its proxies and use them to achieve its objectives in Afghanistan.

The fraying of nerves in Islamabad and Kabul became evident when Pakistan announced that six Afghan spies had been arrested in Balochistan. Matters weren’t helped when the Balochistan home minister, Sarfaraz Bugti, unnecessarily used provocative language while ordering Afghan refugees to leave. The arrests of the NDS spies were being linked to the earlier capture of an Indian spy Kulbushan Jhadav, a naval officer, also in Balochistan.

The fact that he was based in Chabahar, the Iranian seaport being developed by India to facilitate direct Indian trade linkages with Afghanistan and Central Asia bypassing Pakistan, added a mysterious twist to the situation amid talk of an Afghanistan-Iran-India alliance that could isolate Pakistan.

The Kabul-New Delhi tie-up wasn’t a new development and India’s animosity and Afghanistan’s anger against Pakistan was already known. The real worry for Pakistan though was Iran’s attitude as it had painstakingly tried to maintain friendly relations with Tehran by even annoying old friend Saudi Arabia by refusing to join its military intervention in Yemen.

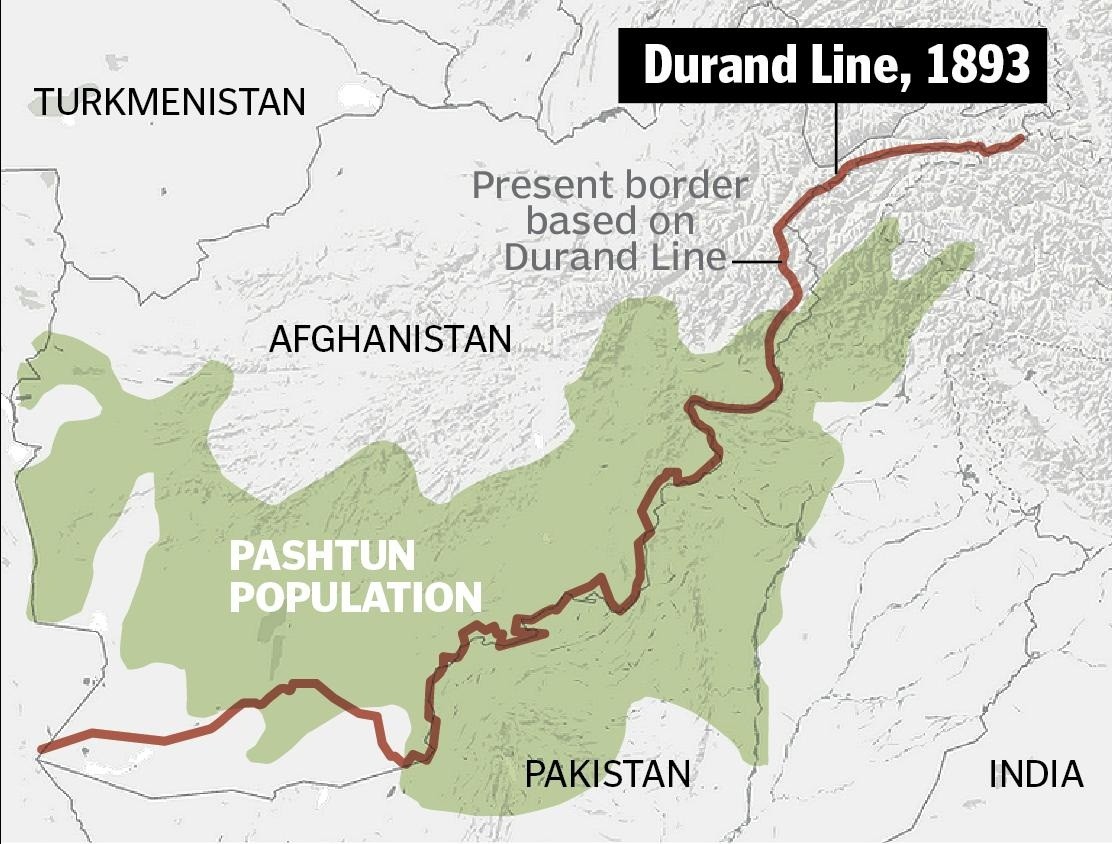

With no breakthrough in sight in resolve the intractable Durand Line dispute and little hope of revival of the Afghan peace process anytime soon, Afghanistan and Pakistan seem destined to continue their blame-game. Overcoming their distrust remains an insurmountable challenge and a major hurdle to normalising Pak-Afghan relations.