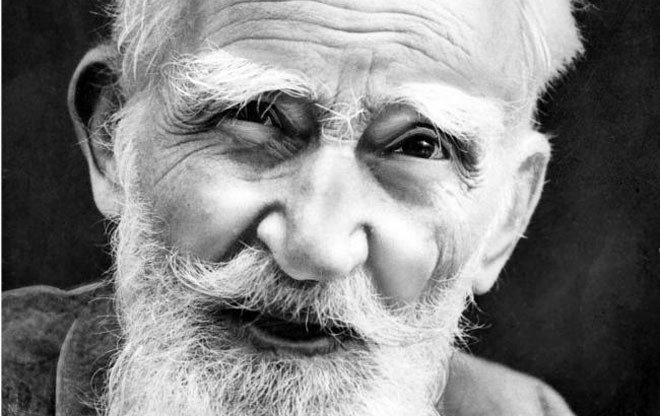

Few writers have been as contentious, as unpopular, as prolific, and as prominent as George Bernard Shaw. He was, of course, one of the greatest twentieth century dramatists. He wrote sixty four plays and playlets with lengthy prefaces (in the eyes of some critics his prefaces sometimes surpass his plays) but he also wrote a hundred and sixty five other books about Fabianism, socialism, political matters, dramatic criticism and musical criticism, not to speak of novels, letters and diaries.

The English never took to Shaw as the Norwegians took to Ibsen or as the French took to Molière. In his lifetime, there was always a hint of suspicion about him partly because he was Irish, but largely because he was brilliant, a man of a mind so nimble and a wit so inextinguishable that it was not easy to map out the cross currents of his motivation. Brilliance is not a value the English admire the most; brilliance is being too clever by half.

There are many volumes of Shaw’s correspondence. He was a vivacious letter-writer. There were people like Gilbert Murray with whom he kept up a correspondence for more than fifty years. Dr Gilbert Murray was a redoubtable Greek scholar and a prodigious translator of Greek tragedy, who took a keen interest in the Stage Society’s productions of his work. He often invited Shaw to come to rehearsals. Shaw nearly always summed up his views in trenchant letters. Murray is right when he says that "each one of these letters shines with Shaw’s genius":

"My dear Murray,

I have for a long time been much concerned about those translations which you are nursing to perfection in the manner characteristic of university professors. Now let me tell you that every university professor is an ass and that you like any common man are subject to this inexorable law. You think that because Gilbert Murray, the poet, is not an ass, Professor Murray cannot be one… . The way to write one good book is to write nineteen bad ones first…"

At the end of his preface to the "Shaw-Terry Letters" -- Dame Ellen Terry was arguably the best known Victorian actress -- Shaw, summing up his regard for her, is stirred by that rare thing in him, the emotion:

"She became a legend in her old age; but of that I have nothing to say; for we did not write and meet and except for a few broken letters did not write, and she never was old to me. Let those who may complain that it was all on paper, remember that only on paper has humanity yet achieved glory, beauty, truth, knowledge, virtue and abiding love."

* * * * *

Shaw’s Irish accent remained as pronounced and as pure as his impishness. His Irishness may not have been as pure, but he never let go of the blarney we associate with the Irish. In the reign of Henry VIII the chief of an Irish clan, who had committed serious misdemeanours, was invited to England. He was put on trial before the Privy Council. One of the indictments against him was that he had burned the cathedral in Armagh. "Well", the Irish Chief is reported to have said, "I burned the cathedral but I wouldn’t have done it; only I was told that the Archbishop was inside it." The irresistible effrontery of such a reply is exactly what we expect of a Shavian protagonist under the circumstances.

The Irish character, my friend Stephen Boyd (who became a charming movie star) used to say, lies not in the blood, but in the air, or in the environment. Shaw’s father took young Sunny (Shaw’s nickname) to sea to give him his first dip. Before Sunny went into the water, Shaw senior gave him a serious lecture on the importance of learning to swim. "When I was a boy of fourteen my knowledge enabled me to save your Uncle Robert’s life." Then, seeing that the young lad was deeply impressed, added, confidentially, "and to tell the truth, I was never so sorry for anything in my life afterwards." Having told this, Shaw recalls, his father had a thoroughly refreshing swim, and chuckled all the way home. From his father G.B.S. inherited a strong streak of alternating between seriousness and puckishness.

* * * * *

Shaw was brought up in an atmosphere of music and learned before he had learned anything else, every note of many great operas. His mother had a fine voice and she belonged to a circle that gave musical performances. Her guru was a man named Lee who had developed a unique system of training the human voice which he called "The Method". Lee had so much influence over Shaw’s mother that the family along with Lee, moved to a grander house, much to the dismay of Shaw’s father, a lumbering dipsomaniac. In the grand house, Lee’s students gave young Sunny books which he read avidly. Shaw tells us that apart from gaining a thorough knowledge of choral and operatic works, he became familiar with a wide spectrum of literature.

Read also: G.B.S-2

G.B.S. had no proper schooling. He went to two or three private schools in Dublin but found them to be educationally worthless. They were hotbeds of religious prejudices and snobbery against which he soon rebelled. Everything he learnt from then on was self-tutored.

From the time he began working (at the age 17) in an estate agent’s office in Dublin, Shaw had two purposes in mind: learning to do something and getting out of Ireland. Dublin was a filthy city -- a place where young men drivelled their lives away in slack-jawed obscenities. "To this day", he was to write sixty years later, "my sentimental regard for Ireland did not include the capital."

G.B.S. left for London when he was twenty. He never again lived in Ireland. He did not cross the channel out of love for England. "England", he was to write many decades later, "had conquered Ireland so there was nothing to it but to conquer England."

His mother had already left his father and moved to London with her two daughters. Shaw has said that he knew very little about his mother. She did not concern herself with him and made young Sunny miserable by neglect. She remained a "grievously disappointed woman, embittered by their ridiculous poverty". In her eyes he was an inferior little male animal tainted with the weakness of her husband, and she despised him from the moment she got married to him. The first drama Shaw wrote as a boy was a passion play in which the mother of the hero was a termagant.

(to be continued)