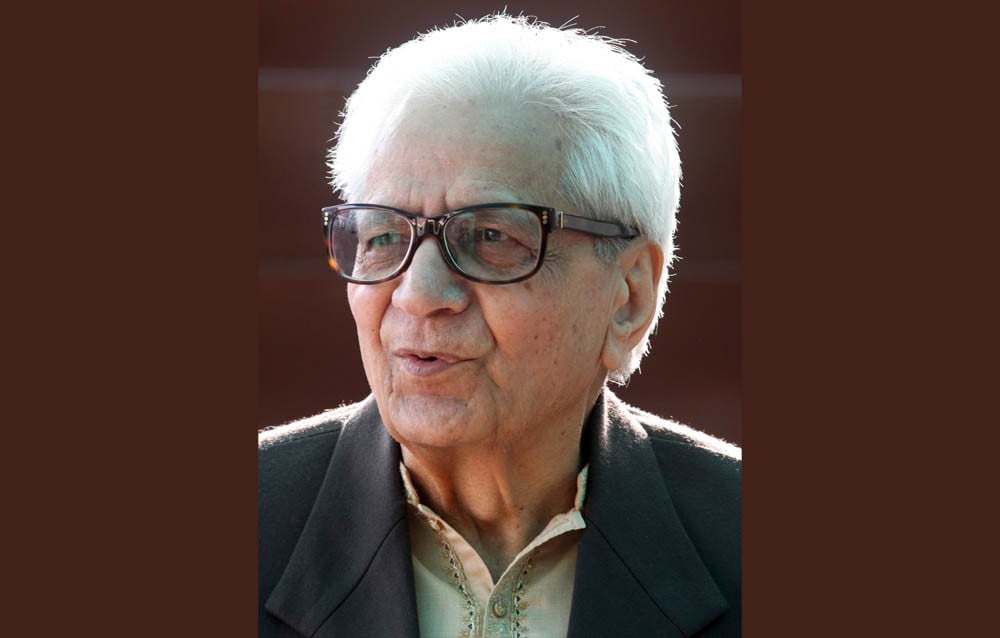

-- Interview with Shahid Hameed

Although the institutions in this country are weak, and the already developed institutions have been destroyed in the last 68 years or so, we have had personalities who work as institutions.

Shahid Hameed, no doubt, falls in the list of such people. He has not only translated voluminous literary works single-handedly -- War and Peace, Brothers Karamazov and Pride and Prejudice to name a few -- without any official support, but has also penned a new English-Urdu dictionary which is in the process of being published. Recently, he has written his memoirs that are set in the pre-partition Punjab where he had spent the early part of his life.

When I asked him why he chose not to write about the post-independence memoirs, especially his long associations with Nasir Kazmi and Intizar Husain, his journalism days in Daily Afaaq where Professor Muhammad Sarwar (famous for his work on Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi) was his mentor, he simply laughed out loud and said: "I have very bitter memories of post-independence times in Pakistan which I don’t want to share. I want to share the pre-independence memoirs with young people so they can have an idea about their socio-political and cultural legacy. It is up to the readers to decide whether I have been successful in doing that or not."

Excerpts of interview follow:

The News on Sunday (TNS): You are a Punjabi and in your memoirs you have used many Punjabi words. You write about the Punjab but in Urdu. Isn’t that strange?

Shahid Hameed (SH): I am proud of my Punjabi identity and love of Punjabi language and I know that we had a strong Perso-Punjabi past which was destroyed by the colonial rulers after the annexation of the Punjab in 1849. Imposition of Urdu in the Punjab was a conspiracy. When I started schooling, Punjabi was not an option in schools. Our teachers were very smart, so they often used Punjabi in classes informally and I recorded many things in my book too. We should introduce Punjabi in schools. There is no alternative to mother tongue. Irish language played an important role in the resistance movement against the English.

TNS: What has been your journalistic experience like?

SH: I worked in daily Afaaq in the early years of Pakistan. I introduced Intizar Husain but Sardar Fazli, a senior person in the editorial, refused to accommodate him. Later, the owner Mir Noor Ahmad agreed and Intizar started writing. The owner of Afaaq had good relations with Mian Mumtaz Daultana. In the early years of Pakistan, there was a power struggle in the Punjab between Daultana and the then CM Punjab Nawab Iftikhar Hussain Khan Mamdot. Nawa-i Waqt was a supporter of Mamdot while Afaaq was supporting Daultana who was also the blue-eyed boy of PM Liaquat Ali Khan.

While working at Afaaq, Professor Sarwar used to identify personalities that I was to interview. He usually guided me in developing questions for the interview. One day, he told me to interview Manto and I did. I remember that Muzaffar Ali Syed did not like that interview.

Unfortunately, we are masters in destroying archival record. Once I needed that interview but failed to find the Afaaq file in any public library. Much of our history is recorded in newspapers like Imroz, Pakistan Times, Afaaq, Civil & Military Gazette etc. but we have no record of these newspapers in our public libraries, which is shameful.

TNS: In the book you have criticised the selection of Liaquat Ali Khan as the first prime minister of Pakistan.

SH: Yes, Husain Shaheed Suhrawardy was the best choice. Selection of Karachi as the capital and malpractices regarding evacuee properties of Hindus and Sikhs were the two prime wrong decisions in early days. Mian Iftikharuddin had good vision regarding the distribution of evacuee property and settlement of muhajirs. But the feudals under the leadership of Liaquat Ali Khan opposed him and Mian Iftikharuddin had to voluntarily resign from his ministry only after three months of being in office in 1947.

The biggest failure of Liaquat Ali Khan was his incompetence or lack of interest in constitution-making. Indian politicians did it promptly and held elections too. But here the prime minister instead of making constitution imposed the tricky Objectives Resolution within six months of the death of the founder of the nation. It proved fatal for democracy and the country.

TNS: Why are you an admirer of Rao Bahadur Sir Chhotu Ram?

SH: I saw Chhotu Ram in my village where he was invited by our MLA and I have penned the whole incident in my book. He was a strong Unionist minister. Chhotu Ram had tremendous respect among peasants and small land holders throughout the Punjab, irrespective of religion. Through three amendments in the Punjab Land Alienation Act 1901, he helped the Punjabi peasants against the ruthless money-lenders.

TNS: Tell us something about Islamia College?

SH: When I was studying in Islamia College (Railway Road), we used to go either to station or to Arab Hotel. I saw intellectuals like Chiragh Hasan Hasrat and Abdul Majid Bhatti there. The railway station had a great attraction for students of Islamia College; they used to go there before arrival of certain trains and stare at ladies. It was common among hostel residents like me.

TNS: How difficult were the days when you moved from Jalandhar to Lahore?

SH: After partition, we settled in a village 62/12/L that was 16 miles from Cheechawatni. It was a very difficult time and I was married too. Vehari Bus Service, owned by a Sikh family, was the only mode of travelling. Our village was three to four miles away from the bus stop and we used to go by foot.

Then I shifted to Lahore in search of job. I started working as a teacher and also newspapers. In newspapers, I often did night duties. I met with Professor Sarwar who was associated with Afaaq. He offered me a job which I did for quite long time. It was an interesting experience. Meanwhile, I passed my MA and through Public Service Commission I got a government job. My first posting was in Multan. Soon I was transferred to Sahiwal and with the help of friend Iftikhar Husain Shah, I was finally transferred in Lahore.

In Government College Sahiwal, I was a part of teacher politics too. As I knew many journalists in Lahore, our news often got space in the newspapers. One of them was famous journalist Amjad Hussain who worked at the Pakistan Times. He often published our activities at the Pakistan Times in those days.

TNS: What attracted you to literature?

SH: I used to go to Pak Tea House with my friend Ahmad Mushtaq in the early years of Pakistan. At that time Pak Tea House was a junction for literary figures. Here I met Nasir Kazmi, Intizar Husian and Zahid Dar. I attended Halqa Arbab-e Zauq meetings too. It was an important time, regarding left and right ideological discussion in literature. Intizar Husain was against progressive thoughts while I was more of a moderate. I was more inclined towards progressives rather than conservatives. Although Intizar was not from Delhi, his Urdu was far better than Dilli wallas.

TNS: There are many Urdu dictionaries, why prepare another one?

SH: While teaching and translating books, I realised that in the presence of these infected and confusing Urdu dictionaries how can students learn the language. When Dr Jameel Jalibi produced Qaumi Angrezi-Urdu Lughat in 1986 published by the National Language Authority, I wrote a detailed criticism. After my retirement from Government College, Lahore (1988), I started the herculean task on an exhaustive English-Urdu dictionary. In so many entries, you often find difficult translations in Urdu dictionaries.

One major reason of downfall of Urdu in current times is its misleading lughats. Issue of pronunciation is also very tricky in Urdu and over-emphasis on words like ‘estation’ and ‘espatal’ for station and hospital are among bad examples in this regard. So I penned an article ‘Tallafuz ka Masla’. Now the dictionary is with the publisher.