The questions that immediately arose in the aftermath of the Objectives Resolution in March 1949

Sovereignty is a very important concept both in terms of law and governance, as well as society. It is a deeply contested notion, and has led to several revolts in history, from the Glorious Revolution in England in the eighteenth century to the French and American ones a century later. Even today it remains an important concept and has critical implications for the rule of law, development of government, and growth.

The modern concept of popular sovereignty developed in the social contract schools developed by Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau in the mid-seventeenth to mid-eighteenth centuries. Both Hobbes and Locke argued that the people were the main agents in a society and that they in order to escape the ‘state of nature’ came together to form a ‘social contract’ in which they agreed to give up some of their rights and freedoms in exchange for all others doing the same in order to achieve peace, security and stability.

Further, while Locke envisaged the social contract to exist in various forms, Rousseau, in his seminal work ‘The Social Contract’ envisioned a political order along the lines of a republic. The legitimacy of a government is, for Rousseau, derived from the people in a democratic sense.

In Pakistan, the question of sovereignty immediately arose in the aftermath of the presentation of the Objectives Resolution in March 1949. The first article of the Objectives Resolution clearly stated that ‘sovereignty over the entire universe belongs to God Almighty alone,’ and that it has been delegated to the ‘state of Pakistan’ but ‘through its people’ and that it is to be exercised within ‘limits prescribed by Him.’ This one sentence description of sovereignty sets upon its head the modern concept of the sovereignty of the people.

In the Islamic tradition, sovereignty rested with God, and could be exercised by the people in a limited way, circumscribed by the laws of the Quran and Sunnah of the Prophet Mohammad. Hence people were not ‘free agents’ as envisaged in the Western model. A number of modern Muslim theorists including Maududi and Javed Iqbal agree with this understanding and argue that in an Islamic country only laws dictated by God, rather than the people, should be enforced.

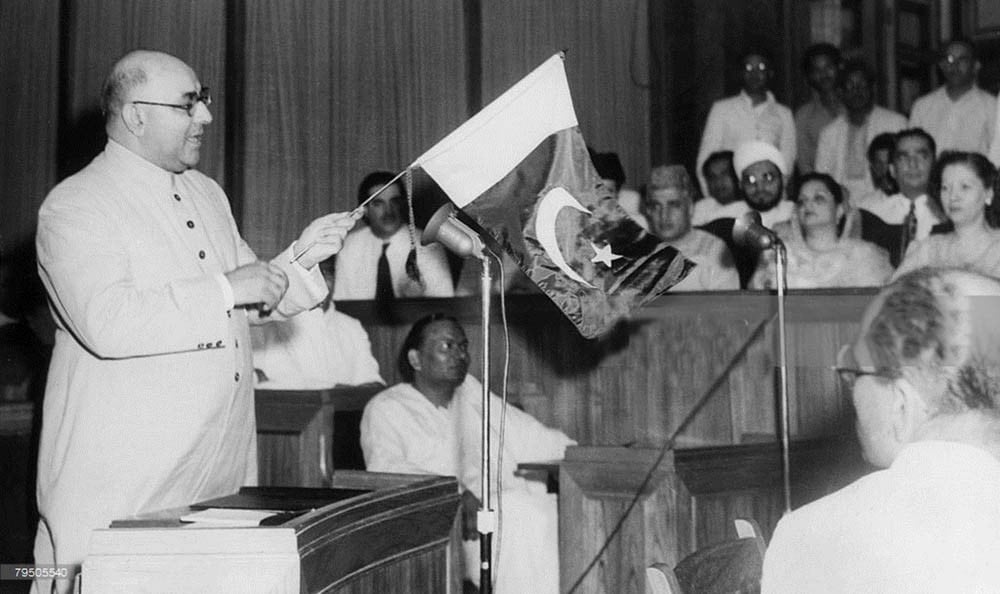

In the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan [CAP], the concept of sovereignty was hotly contested by the two interest groups which had developed, the Muslim versus the non-Muslim group. In his opening speech, Liaquat Ali Khan emphasised that the article defining sovereignty was important since ‘All authority is a sacred trust, entrusted to us by God for the purpose of being exercised in the service of man…’ He further explained that this article did not mean that any type of tyranny would be established by anyone; in fact, Liaquat contended that ‘the Preamble fully recognises the truth that authority has been delegated to the people, and to none else, and that it is for the people to decide who will exercise that authority.’

The members of the Pakistan National Congress were quick to find problems with the wording of the article on sovereignty. What if someone declared himself to be chosen one of the Almighty and make himself supreme, asked Mr Bhupendra Kumar Datta? Mr Datta similarly questioned the putting of the state before the people in the order of delegation and wondered if this led to the ‘deification of the state’? His colleague, Professor Raj Kumar Chakraverty, dwelled further on this issue and argued that the state should not become ‘supreme over the people’ and moved an amendment to replace the phrase ‘the State of Pakistan through its people,’ with ‘people of Pakistan.’ His reasoning was that in the current wording it could seem that the state ‘can wield its authority in any way it likes, of course under God.’

He argued that ‘a State is the organised will of the people, a State is formed by the people, guided by the people and controlled by the people…But as the words stand in the Preamble, it means that once a State comes into existence it becomes all in all. It is supreme, quite supreme over all the people.’

Another member of the CAP, Mr Prem Hari Barma, objected to the ‘limits prescribed by Him [God],’ mentioned in the first article were, and moved an amendment to remove this clause. He contended that no human being could do anything without it being permissible by God, so if the resolution was pointing out this obvious fact then the clause was superfluous. Otherwise, who was to judge what ‘limits’ did God enjoin upon the exercise of His sovereignty by the people? Mr Barma argued that ‘Each one of the paragraphs of the Objectives Resolution should be self-explanatory…Had the limitations state in the paragraph been of universal knowledge to all, then retention of the word would have been appropriate.’ Herein was the crux of the problem.

While the sovereignty of God might be argued as an abstract and thus compatible with modern notions of democracy, the real issue was the fact that His sovereignty was not being delegated to the people directly, but through the state, which, as mentioned above, could become supreme. Furthermore, the vagueness of the ‘limits’ prescribed by God on the exercise of His sovereignty created another problem as to who would decipher what these limitations were and how would they limit the function of the sovereignty of the people and the state. The constitution envisioned by the Objectives Resolution was thus limited by the existence of a powerful state and ‘limits’ prescribed by God.

Concerned that sovereignty was not going to rest with the people of the country, another member of the CAP, Mr Kamini Kumar Datta, introduced about two amendments which stated: ‘Wherein the National Sovereignty belongs to the people of Pakistan; Wherein the principle of the State is Government of the people, for the people, and by the people.’ Here Mr Kamini Datta explained that in the proposed resolution there was no clarity as to ‘…in whom actually in the functioning of the constitution -- the very basic factor to be considered -- does the actual sovereignty lies.’ He further wanted it made clear that ‘the basic fundamental principle of the constitution must be to make the people understand it as government by the people, of the people and for the people. No equivocation is permissible therein.’

Interestingly, Mr Kamini Kumar interpreted the ‘people’ in a broad sense, marking them as citizens of the state without discrimination on any basis. He contended: ‘In accordance with the spirit of Islam the Preamble fully recognises the truth that authority has been delegated to the people irrespective of whatever faith they may follow, and to none else and that it is for the people to decide who will exercise that authority.’ This was obviously done so that the notion of Dhimmis -- protected non-Muslims with limited rights -- does not creep into the conception of the state. If the state were to remain democratic, Mr Kamini Kumar exclaimed, it must treat all its citizens equally.