Factual information about life, random anecdotes from the writer’s charmed existence as a successful film critic and more make up this book on all things Indian

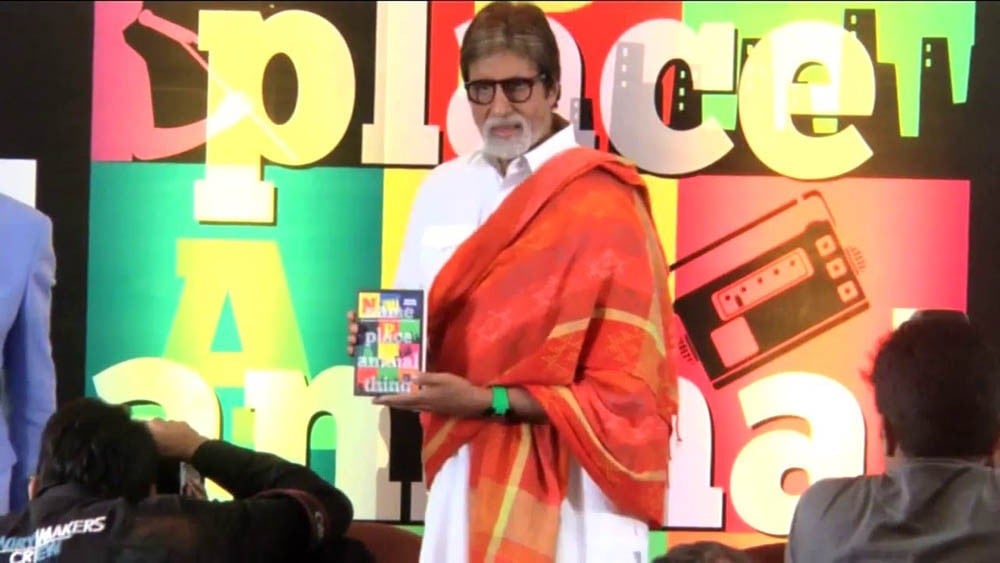

Mayank Shekhar is a well-known name in Indian film and television circles. Big enough that the Big B of Indian cinema, Amitabh Bachchan himself graced the launching ceremony of his debut book, Name, Place, Animal, Thing.

The book, which takes its title from the name of a popular memory game, is a choice collection of newspaper columns and blogs written by Shekhar over a period of five years.

The volume’s self-description as ‘part rant, part reportage’ is perhaps the most succinct summary of Shekhar’s literary endeavour. Factual information about life in the Indian state weaves in and out of seemingly random anecdotes from Shekhar’s charmed existence as a successful film critic.

The rants and reportage are not linear though.

The rants are mostly outbursts of frustration at the disjointed logic applied across Indian society in matters of daily living and (mis)governance. The reportage moves along the same lines. Both end with a similar sense of weariness and the futility of attempting change.

Yet, there is order in chaos. The numerous opinion pieces are organised in four sections, borrowed in order from the book’s title, and then further categorised into separate chapters.

It is clear that Shekhar knows how to catch the reader’s attention. Pop culture references are snuck into popular phrases to form chapter titles like Rah rah over Rahman!, This Expat Import business and Tweeter ke aagay do Tweeter!.

With journalism and writing being his chosen field, it is not surprising that Shekhar devotes a relatively large amount of space to explore the rising popularity of different avenues available for self-expression today. The blogosphere, of which Shekhar himself is a proponent, and Twitter, are projected not just as the internet age’s medium of instant communication, but also come across as tools to circumvent red-tapism in Shekhar’s India.

The power of popular culture and its flag bearers is the declared focus of the compilation. Each story, whether it is about the situation of Indians abroad or the local religious festivals, is a local’s perspective on a culture best known for its exoticism. Amusingly, ‘Peep’ shows appear to be Shekhar’s pet peeve. His grouse with the ease of providing too much information through forums such as Facebook and Twitter is offset only by his distaste for the prevalence of hierarchies and prejudices in Indian society. Caste, creed, and identity continue to define every aspect of social living in his world.

India and Indianness reign supreme throughout the book. Each one of the numerous experiences related by Shekhar is informed by his identity as an Indian. In keeping with the author’s association with the Indian entertainment industry, Bollywood is the symbolic and literal soul of the book.

But the book is about much more than an industry insider’s recollections -- it captures, albeit in a circuitous manner, the enduring international fascination with all things Indian.

His attempts to present an unobstructed view of life in today’s India are, as he repeatedly acknowledges, tinged with the subjectivity of his personal prejudices. As alluded to in the book’s title, nostalgia and its cohort, memory, are innately linked to personal and collective identity. Shekhar admits that entertainment is escapist in nature and though he tries to stay away from what he terms political bak bak, every one of his casually told anecdotes touches upon a socio-political nerve.

With memory and identity taking centre-stage in Shekhar’s book, how can the complex riddle of the migrant experience be far behind? While certain blogs detail his time as a representative of his country abroad, Shekhar believes that every person is a migrant in today’s global village. In spite of his repeated assertions of the uniqueness of all things Indian, Shekhar is savvy enough to realise the universal prevalence of experiences mirroring his urban existence.

The Indian millenial’s experience, then, is not dissimilar to that of his Pakistani counterpart. From his commentary on intellectual, material, and cultural snobbery to the danda raj of local law enforcement agents, there is not much in this Indian journalist’s book that a Pakistani cannot relate to. The difference in scale and size of populations and cities being apart, Shekhar’s observation about builder being ‘king’ could just as easily be a remark about the rapid expansion of concrete jungles in Pakistan as could the perennial tussle between city loyalties. This commonality of the modern man’s experiences does not come across as part of the book’s integral message, but rather arises out of the sheer similarity of Shekhar’s recollections to such columns regularly published in Pakistani newspapers and magazines.

Name, Place, Animal, Thing is not a somber study of Indian culture -- and neither was it intended as one. It is a journalist’s attempt at presenting an unclouded picture of a society where even the slums have been romanticised by western media.

As Shekhar reiterates throughout the book, living and flourishing in India requires street-smart survival strategies. Accordingly, he has kept his writing style and tone both simple and uncluttered. Interspersed between his memories are the journalist’s philosophical musings.

At no point does the writer stray from his chosen light-hearted, casual style of writing. There are digressions galore but Shekhar’s witty pop culture references stop them from becoming unbearable. At 400+ pages, the book does tend to ramble on, and as the author advises at the outset, it is better to consume it in bits and chunks in no particular order to avoid indigestion of any kind.