Mah e Mir liberates us from the national narrative and sends us home to live our slow lives with private griefs

The question of the purported revival of the cinema industry in Pakistan comes up again in the new release, Mah e Mir, raising some huff, puff and bluster in the media for its unusual content. A thinking film that some reviewers have called ‘torturous and boring’ and others ‘quite unnecessary’ with still others commending it for the script written by Sarmad Sehbai but nothing else besides, the film has not gone unnoticed. The proof lies in the pudding, of course, or the khir, if you prefer, but what is interesting is the reactions to it and the questions it raises about cinema in Pakistan today or any intellectual endeavour for that matter.

To begin with, how could this film, or any other, resurrect the dead? The cinema we had in the 1970s and early 80s is long gone, along with its audience. Earlier cinema was class divided too between romantic Urdu films for the middle class audience comprising mostly women and college students, and gritty Punjabi vendettas on social justice that were popular among the working class in general. There was very little crossover between the audiences of the two kinds of cinema, for instance, someone who considered him/her self middle class wouldn’t be caught dead watching a Punjabi film because it spoke to a different imaginary, a different aesthetic.

In between all this was the brilliance of Bengali producers, directors, actors and musicians in the times of East Pakistan and some wonderful adventures in the 1960s up to the early 80s by maveriks like Khwaja Khursheed Anwar, Rasheed Attre, Riaz Shahid, Rehman and others who were often left broken financially and in spirit by their singular experiments. Gone forever is that social milieu, or rather the socialist milieu, of those films. Gone, too, is Bangladesh, where better films continue to be made.

New cinema post 2011 is funded by foreign agencies and the government (read:the ISPR) with a heavy handed agenda aimed at the middle and upper middle classes bred on the staple of Indian films. The audience is now ‘educated’ in a very class conscious way, mesmerised by the social media, a pretender who speaks Urdu with an American lilt and likes to eat popcorn at the movies. This audience is generally wary of anything ethnic or locally grown, unless it is the usual disparaging commentary on ‘the condition of Pakistan’ and how to get out of here alive, the apology for terrorism being bred here, the case of the minorities and the demeaned status of women etc packaged and endorsed by international media houses that direct the storyline of this country and award weak, propagandist work like that of Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy. New wave Pakistani intellectuals and artists (and anyone half-way educated) tend to subscribe wholeheartedly to this self-loathing in painting, in novels in English, and most certainly in cinema, in the hope of gaining proximity to international capital.

As for the poorer sections of society, cinema today is an expensive idea considering the cost of ticketcs and how cineplexes are located in upper class ghettoes.This has spawned a kind of vernacular cinema for working class men -- soft porn in Pushto films, caste wars in Punjabi/Lahori films shown to small audiences (often with a porn clipping) , and films made in Lyari on the gang wars and the warlords. The classes stand ever more divided in self representation and in creative production, to the detriment of both.

Where Mah e Mir comes into all of this is that it cares not for catering to established bad taste, is not funded by foreign or local agencies and -- for all its rawness and its minor glitches -- locates itself in art and not in post 9/11 politics. Written in a sophisticated Persianised Urdu with poetry by Mir Taq Mir that is both sung and recited, it is not a biopic or history drama but a mirror for the young poet to look into. A mirror equally reflective of creative people of other kinds, harassed by the authority of those with wealth and power who are in the business of directing tastes and manufacturing truths. Sehbai’s artist is a tormented, solitary soul who lives on the outskirts of society but holds on to the dream and believes, believes that writing with heart may still be possible, that love may be possible, without expecting any returns from either. In this, the artist is closest to the malamati fakir or the qalandar, a subliminal thread that runs through Mah e Mir.

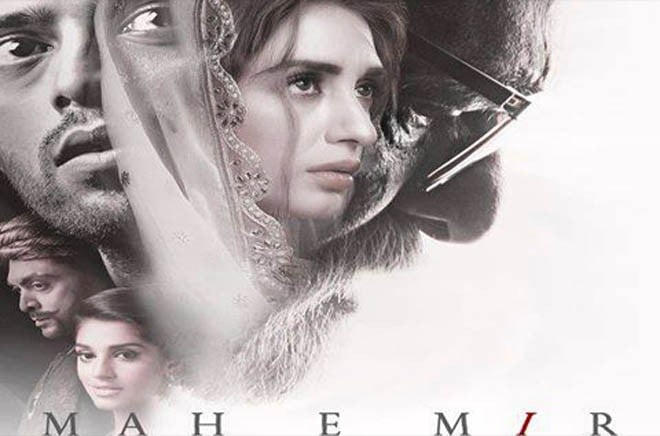

Set against a rich viusal repertoire of what looks like Karachi’s old city and elaborate sets in the historical falshbacks to Mir’s life and times, the film is visually engaging with a musical score (Mir’s poetry composed by Sehbai) based on the classical and also on the coke studio version of qawwali. It has a cast of some of the best young actors that television has produced: Fahad Mustafa, Iman Ali, Sanam Saeed, and Aly Khan among others. This was Fahad Mustafa’s film debut, although several other films he has worked in since were released before Mah e Mir. A hard-working actor, he manages a most unself conscious portrayal and carries the burden of the narrative, and if his doleful eyes don’t get you, his bad-hair-life will. Iman Ali does what she does best, she acts with her body not in any sense vulgar but through presence and movement and gestures instead of relying on dialogue delivery alone. Manzar Sehbai is superlative as the pedant who has lost his soul, groomed as he is in the tradition of European theatre and not in commercial cinema, he brings to cinema his dedicated method acting. Sure, the younger actors appear awkward in places and Sanam Saeed (who plays an entirely charming negative character) is candid enough to admit there are raw edges to her work of three years ago, for that is how long this film was in the making.

Since the brave indie producers of Mah e Mir have retrieved their investment in the two weeks since its release and are now looking at profits, local cinema may finally be encouraged to move out from under the Bargad-like shadow of television where the best talent has taken refuge for years but where nothing new can grow. Mah e Mir may have been conceived as an ‘art movie’meant to do the round of festivals but it has done just as well in city theatres, thereby defying the label of being ‘parallel’or elitist. The film looks good, so good that you would imagine it is big budget, but as Iman Ali put it in an interview, it banks on the ‘talent and passion’ of everyone who worked on it. She also gives the best answer to the question if Mah e Mir is about reviving Pakistani cinema. She smiles and double queries: "Was Mir Pakistani?"

In that sense alone, Mah e Mir liberates us from the national narrative, rests us from living in Pakistan always in a ‘critical condition’, sends us home to live our slow and often sonorous private lives with private griefs and some intellectual pursuits, like people anywhere in the world.