Recalling two great upheavals that shook Asia 50 years ago

Perhaps the worst crimes against humanity are those that target people just because they are different -- either belonging to a cast, creed, or race that is not dominant, or professing an ideology that is frowned upon by the powerful segments of society.

If we look at the annals of the mid-1960s’ Asia, we are horrified at the magnitude of two tragedies that befell the people of China and Indonesia, not by chance or fate, but by planned atrocities. In China, the follies of Chairman Mao coupled with his megalomania initiated a Cultural Revolution, and in Indonesia it was fear of communism that prompted the army and the rightist vigilantes to launch mass execution of millions of left-leaning and secular-minded people.

Prophets of doom who love to propagate despondency at the current state of affairs in Pakistan will do better if they turn a couple of pages and look at just half a century back. Exploring the turns of history that other countries have gone through gives one hope that if other societies can come out of a much worse morass, Pakistan still stands a chance.

Both China and Indonesia had suffered under foreign occupation, waged long struggle for independence and produced charismatic leaders who were master orators with a tendency to womanise. Both countries had the largest communist parties in the world and after independence within two decades suffered huge losses in terms of human lives and dignity at the hands of their own countrymen and not by any foreign invaders.

The People’s Republic of China came into being in October 1949, and after just two months the United States of Indonesia emerged on the map in December. The early 1950s saw the consolidation of power by the Communist Party in China and the emergence of a shaky ‘liberal democracy’ in Indonesia. In both countries, the events of late 1950s sowed the seeds of discontent that paved the way for the upheavals of 1960s.

In China, the Communist Party had won the hearts of the people during a long struggle against the Japanese and the Nationalists; religion hardly had a role to play in the post-revolution peoples’ republic. In Indonesia, the situation was different; the Muslim majority was highly religious and a reformist socio-religious movement -- Muhammadiyah, influenced by Wahhabism -- had been founded in 1912 by Ahmad Dahlan, a follower of Egyptian reformist Muhammad Abduh. Then in 1942, during the Japanese occupation, a group of Muslim militias started a new group called Darul Islam (Islamic State) that recognised only Sharia as a valid source of law.

In an attempt to control Islam in Indonesia, the occupying Japanese had established Masyumi -- an organisation that became the largest political party following the Indonesian Declaration of Independence. Masyumi included the Islamic organisations such as Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah. In the 1955 elections, Masyumi won more than 20 per cent of the popular vote with 57 seats in the parliament; it was most popular in regions such as Aceh, Jakarta, Java, and West Sumatra.

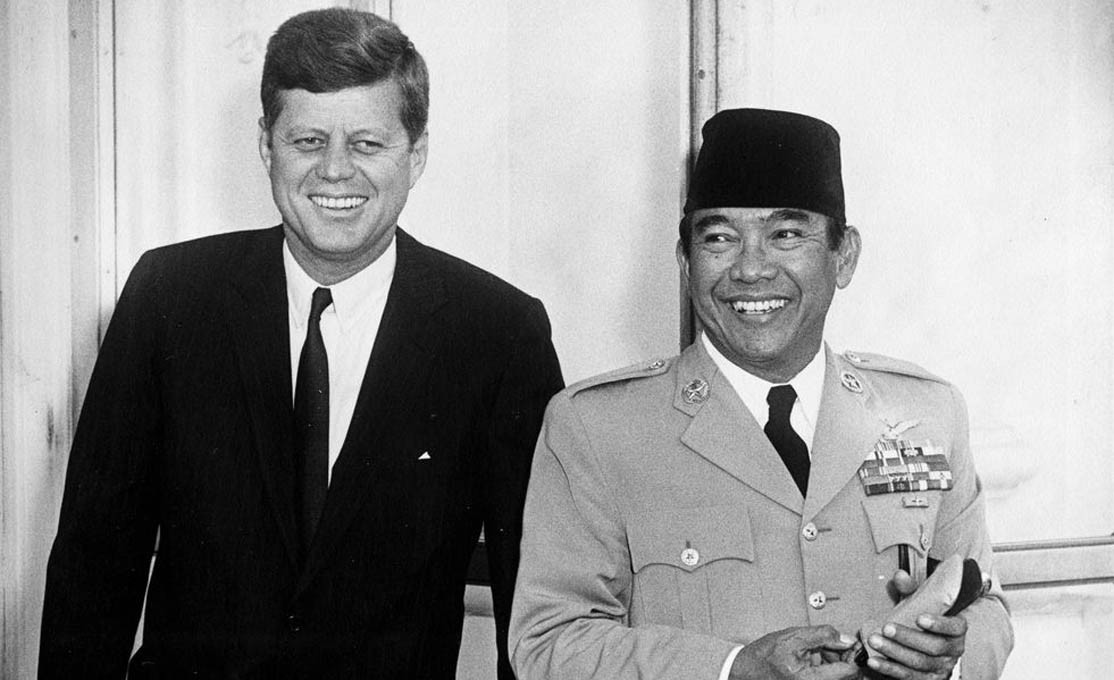

Indonesia in the 1950s had some similarities with Pakistan; there were forces that wanted to draw an Islamic constitution for the country and there were groups that preferred a secular orientation for the state. The main difference was that Indonesia had a secular leader in Sukarno who was also considered father of the nation; whereas in Pakistan after the death of the founding father, the leaders were too eager to pander to the religious sentiments of the people.

The 1950’s Indonesia was marred by the rebellions led by Darul Islam for the establishment of an Islamic state. Elements of the Indonesian army, who believed that Indonesia should be an Islamic state, deserted and joined the Darul Islam. The rebellion and the failure of political parties to establish a firm ‘liberal democracy’ resulted in the imposition of martial law in 1957 by President Sukarno who then tried to introduce a ‘guided democracy’.

Just like Pakistan, Indonesia had seen a rapid turnover of coalition governments including 17 cabinets between 1945 and 1958. Though in the 1955 elections the Indonesian National party (PNI) -- considered Sukarno’s party -- topped the poll, the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) and its arch enemies in Islamic groups united in Masyumi party received strong support; no party garnered more than a quarter of the votes, resulting in short-lived coalitions.

Paving the way for a presidential system, Sukarno strongly criticised parliamentary democracy and used almost the same arguments that were later picked by General Ayub Khan in Pakistan. Sukarno presented his three pillars of ‘guided democracy’ i.e. nationalism, communism, and religion trying to pacify both religious and secular aspirations of the people (remember Bhutto’s Islamic Socialism?).

In this tug of war between the Islamist and secular groups in Indonesia, Sukarno himself was inclined towards secularism and communism but his was not a party that could openly proclaim a communist revolution as the Chinese Communist Party had done in China. Sukarno had to walk a tightrope holding a balancing pole in his hand with the Islamists on one end and the communists on the other.

In that era of Cold War, the USA was not a silent spectator and any left-leaning leader was a target of the CIA that started meddling in the Indonesian affairs with a solid support for the Islamists (remember the Afghan mujahideen of the 1980s?). CIA’s efforts to subvert the Sukarno government in the 1950s failed, resulting in further attempts to infiltrate the Indonesian army. In 1958, some Masyumi members joined the rebellion against Sukarno and by 1959, things came to a head; on July 5, 1959, the armed forces supported Sukarno to dissolve the constituent assembly (remember July 5, 1977 in Pakistan?).

Sukarno assumed strong presidential powers with the additional role of prime minister and embarked on the journey of his new and ‘guided democracy’. Factions of the Darul Islam in South Kalimantan surrendered in 1959 after their leader was killed. The Darul Islam forces were shrinking in size and by 1962 there were only pockets of resistance in West Java and South Sulawesi.

During this period, the Communist Party of Indonesia (KPI) supported Sukarno as he was trying to crush the Islamist rebellion. The KPI gradually increased in membership and was seen as close ally of the president, much to the chagrin of the Islamists, the CIA, and the American agents in the army. By 1965, the KPI had become the largest political party in Indonesia and was openly aspiring for power. As the KPI became bolder in overtures towards power, the rightest elements in the Indonesian society became restless.

Though Sukarno was one of the founders of the Non-Aligned Movement, he was increasingly leaning towards China and in 1965 openly held America responsible for creating troubles in Indonesia. This precipitated an onslaught against the communists who had allegedly tried to stage a coup by killing top generals of the Indonesian army. This abortive coup in which six of the seven top army generals (barring Suharto) were killed on September 30, 1965 rocked Indonesia and gave a justification to the army -- now led by Suharto -- to launch a massive purge not only of communists but also of all leftist, progressive, and secular people.

Suharto and the right-wing military generals led people to believe that the communists were bent upon taking over Indonesia and to prevent these ‘atheists’ and ‘antireligious monsters’ it was imperative to exterminate all traces of leftist elements in society. Thus began a mass massacre across Indonesia that targeted millions of people who had any connection, real or purported, with KPI. Vigilante groups were formed, mostly led by Islamist groups and even supported by criminal elements in society who were wielding machetes, guns, knives, wires, robes, wooden spikes, or anything else that could be used to maim, mutilate, and kill leftists and their families.

During the 1965-66 political turbulence and violence, Muhammadiyah declared the extermination of the communists and their sympathisers constituted Holy War; this view was endorsed by almost all other Islamic groups. The events of this period have been beautifully recreated in two films: Feature film The Year of Living Dangerously (1982) directed by Peter Weir with Mel Gibson and Sigourney Weaver in lead roles, and documentary film The Act of Killing (2012) directed by Joshua Openheimer.

In this melee an oblique contest for power between Suharto (Jakarta garrison commander who later assumed control of the army) and Sukarno (president) ensued in which Sukarno was sidelined and Suharto led the purge that killed over a million people. In March 1966, Sukarno was obliged to delegate wide powers to Suharto who became acting president in 1967 and president the next year. Gradually, Sukarno sank into disgrace and died in 1970; his ideology was proscribed for over a decade and then his name was partially rehabilitated.

After this tragic purge, the country remained under a ruthless dictatorship of General Suharto, supported by the USA, for more than three decades up until 1998. During this period the army entrenched itself into every branch of the economy and the government that pursued an anticommunist and pro-Western stance.