Pakistan has, through its’ nearly 70 years in existence, never been truly free of torture or of killings carried out surreptitiously by police in order to put to death selected persons without trial and without public knowledge.

The mass extrajudicial killings that we see now, with 696 people killed in encounters in Karachi alone in 2015 and almost 1,000 the year before that, may be a relatively recent development. But mistreatment of prisoners and the forceful death of persons by state actors is not new.

A glance at newspaper files, dating back to 1949 or 1950, shows news items very similar to those from more recent years. These items talk of people in villages, towns or cities being beaten by police or mishandled in custody.

It is notable that such reports appear to have become less frequent over the last two decades, but this perhaps is because they no longer make news in a situation where far worse forms of torture and brutality are used more commonly against people by an ineffective police force attempting to cope with the growing problem of crime and terrorism.

Simple beatings are then no longer newsworthy. Torture of anything has become far harsher and, in many cases, more lethal than was the case at the time the country came into existence and through its early decades.

The death in custody of prominent people, such as journalist, poet and Communist Party Pakistan activist, Hassan Nasir, who died at the Lahore Fort allegedly after torture in 1960 made news from time to time. This killing, like others carried out behind the apparently calm ambiance of Ayub Khan’s era in power, made big news with people demanding the exhumation of the body.

In other cases, the wrongdoing behind bars may never have been reported. There were after all extremely tight checks on media reporting, coinciding with the suppressing of communists and others seen by the Ayub regime as being anti-state.

Extrajudicial killings first came to the forefront of our history in 1971, as civil war broke out, and in the months leading up to this. Thousands of citizens of East Pakistan were put to death at the hands of the Pakistan military. Others died due to actions by other state players; in the West wing of the country too; some disappeared; some were silenced.

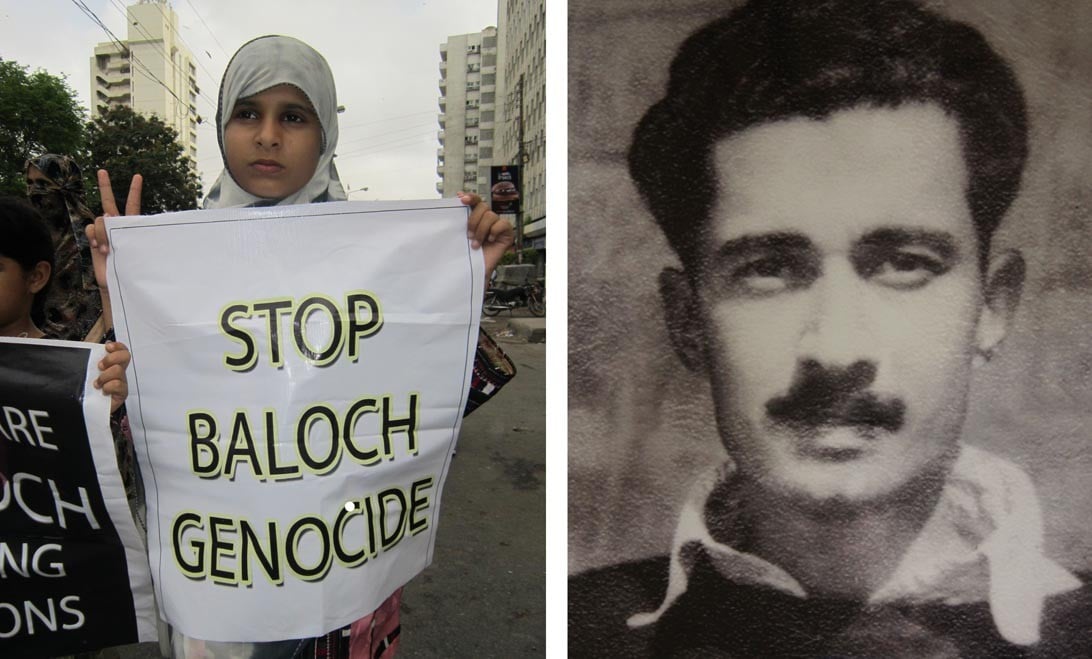

This era of grotesque brutality was perhaps Pakistan’s entry point into the world of mass killings and secret actions by its security forces. Since then, we have seen similar action in Swat, in Karachi, in Balochistan, in KP and in other places.

The fact that Pakistan has not ratified the Convention Against Torture, which it signed in 2008, means it has no definitive mechanism to tackle torture. Although the practice is barred under Article 14 (2) of the Constitution, it is essentially endemic and has spread from police into the ranks of citizens, including mobs who had burned suspected criminals alive, beaten them to death or in some cases hung them from the nearest available tree. This breakdown of basic humanity and the rule of law has been seen decade after decade.

Torture, of course, continues today and has been seen in some of its worst forms on the bodies of people found in towns across the country. In Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s time, we saw torture and its partner -- extra judicial killings -- in Balochistan as well as in use as a weapon against selected political opponents.

The trend continued under General Ziaul Haq, even if the targets were different. And of course, possibly as a result of a global trend initiated by US actions against its enemies, it has grown more sharply since 2001 and the post 9/11 scenario.

Extrajudicial killings or police encounters have been used as a tool by persons, including the Punjab Chief Minister, Shahbaz Sharif, in the 1990s to hunt down criminals and determine outside the ambit of courts who is guilty and who is not, something that Mr. Sharif was taken before the judiciary for.

The question of whether drone attacks in northern areas count as extrajudicial murder is something more open to debate and discussion. The US’s justification of such actions in various countries, notably those in the Middle East, has blurred the lines of thinking.

Essentially, extrajudicial murder, often preceded by torture, has become a convenient way to tackle dissent. We have seen this in Karachi today; we have seen it before; in many forms, in many ways, from one year to the next. It would be hard to find any tenure of government completely free from such actions.

Certainly, the much-needed reform of police and improvement in investigation methods that we need to outlaw torture has never come, and this is the reason why Pakistan continues to come face to face with new rounds of death and bestiality behind bars every year.