Meet Raj Kumar Kapur. When I first heard the name I could not help but smile -- one would be hard pressed to think of a more romantic name. Mr. Kapur has lived a remarkable life which includes the distinction of having played hockey for India. But such is his life that this distinction is hardly the most outstanding thing about his life. Let us journey back a few years.

In June 1947, a 20 year old college student from Dyal Singh College boarded a train from Lahore to visit Calcutta. His family was based in Sargodha and lived in a sprawling haveli. His grandfather was a highly successful lawyer in the Lahore High Court and this young man was no stranger to privilege. But this was no journey of privilege. The journey had become necessary because of most serious reasons: his sister-in-law wanted young Alsatian puppies delivered to her in Calcutta and, as sisters do, she would not countenance anyone being casual about this. So this young man took it upon himself to take the young pups to Bengal. If anyone had asked him about his return plans to Lahore, as he boarded the train, he might have shrugged and said, "should be back in a few weeks". He had friends, family and a college to come back to.

As things turned out, it took him a little longer than expected.

Fast forward to April 2016 and a 90 year old gentleman steps out of a PIA airplane that just landed from Delhi. As he came out of the gates of the Lahore airport, you would have been hard pressed to notice anything remarkable about his gait -- except its eager pace considering his advanced years. Yes, this was the same man who boarded that train for Calcutta. It had been 70 years since he undertook that train journey. 70 years since he had left loved ones, a childhood and his youth behind. That young man, Raj Kumar Kapur, had finally come back to Lahore.

His is just one story. Millions of similar stories, in both present day Pakistan and India, surround us -- even if we do not pay attention to them. August 1947 and onwards, apart from the celebrations of independence and the accompanying violence, was no ordinary moment. For those who survived it and crossed to the "other" side, life was never the same. It was not just as if the uprooted families simply had to leave their homes, friends and memories behind. Not just that. We, people and governments in both countries, essentially told them that not only do we expect you to move away, but we will also make it extremely difficult for you to revisit those places and people you left behind. This was the true partition that happened. We partitioned lives, people, hearts, memories -- before that summer of 1947 and after. The days in Lahore and after. That is how these lives have been defined.

We have all heard stories of massacres and violence, of how "the other" started it first -- and how the violence in our name was merely a reaction. And, yes, violence did devastate lives. It should be condemned regardless of who committed it. But we did not have to use violence by others as a justification to deny dignity to the very people who suffered it on both sides. By doing so we have continued to perpetrate a different kind of violence -- one that insists on division. Partition therefore defined not only the lives and deaths of millions in 1947, it also came to define how we see each other across the border. It, quite literally, partitioned our very existence.

You do not need to stand at the international border between India and Pakistan to feel the division. That division runs through our discourses, often our hearts and our stereotyped beliefs. The people who had their lives uprooted had a connection, a precious bond with the places where they lived. We had no right to sever those bonds decade after decade -- making it almost impossible for the partitioned lives to reclaim a piece of their past lives; the "pre-Partition" existence as we now call it. There is enormous truth in that term.

Yet many memories live on in tales told to grandchildren. A South Asian history textbook based on tales told by grand-parents would probably have a lot more truth and love than the current history books in India and Pakistan. And so it was in Delhi in 2013 that, as I dug into my butter-chicken, Mr. Kapur’s grandson crossed paths with me. "I love Lahore" was the second thing he said to me. Now if you are a Lahori you hear that a lot, both within and outside Pakistan -- I am not being arrogant but merely paying homage to my great city. But soon I realised this was no ordinary comment. Over the course of our conversation, I learned more about Lahore of days past from this new friend than anyone I could think of. This was because his maternal and paternal grandparents had all lived in Lahore. As he told me, his maternal grandfather would say "aj tay Lahore hee ban gaya ay" when he had to compliment Delhi’s beauty. I could not remember the last time anyone had paid Lahore a greater compliment.

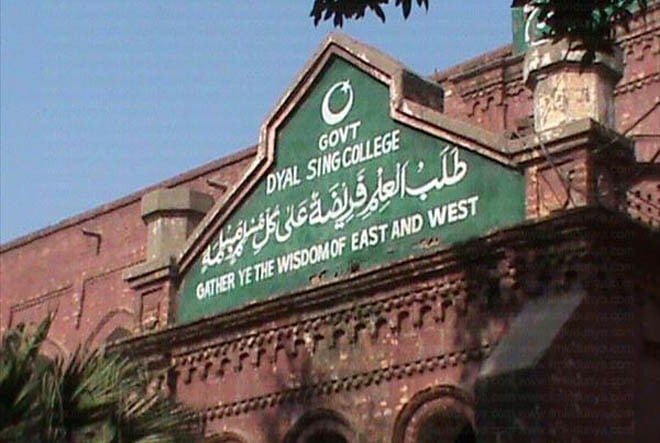

Manav, his family and the senior Mr. Kapur finally visited Lahore late last month. The grin on Mr. Kapur’s face as he went back to his old college -- Dyal Singh -- is something I will never forget. I had to constantly remind myself what a massive moment this was in Dada ji’s life. He had waited 70 years for this and boy he was soaking it all up. You could have filmed each moment, each glimmer of joy and excitement in his eyes and watch it over and over.

One morning as we all went out for breakfast, my friends and I insisted on paying. But the Kapur family had already paid the bill. I protested about this to Manav and his father, telling them that they were in Lahore and this was simply not done -- the hosts will take care of everything. They said, "Waqqas mian, humara Lahore say rishta aap say ziyada purana hai".

I could not argue with that. There was perhaps one less scar in our partitioned existence.