Ajmal Kamal’s recent collection that challenges the ‘established’ views in the realm of Urdu literature

It’s been more than two decades that the prestigious literary magazine Aaj is trying to broaden the canvas of Urdu literature by introducing snippets from world literature to its readers. Its contribution in enriching our literature is stupendous, to say the least. The special issues of Aaj, such as the one devoted to Gabriel Garcia Marquez, are in great demand even today, as readers still cherish reading the hefty volume which is arguably the best one on the master writer in Urdu. Or how can we forget the two volumes that were devoted to the evolution of Karachi, and dealt with the social and cultural history of the city by the sea?

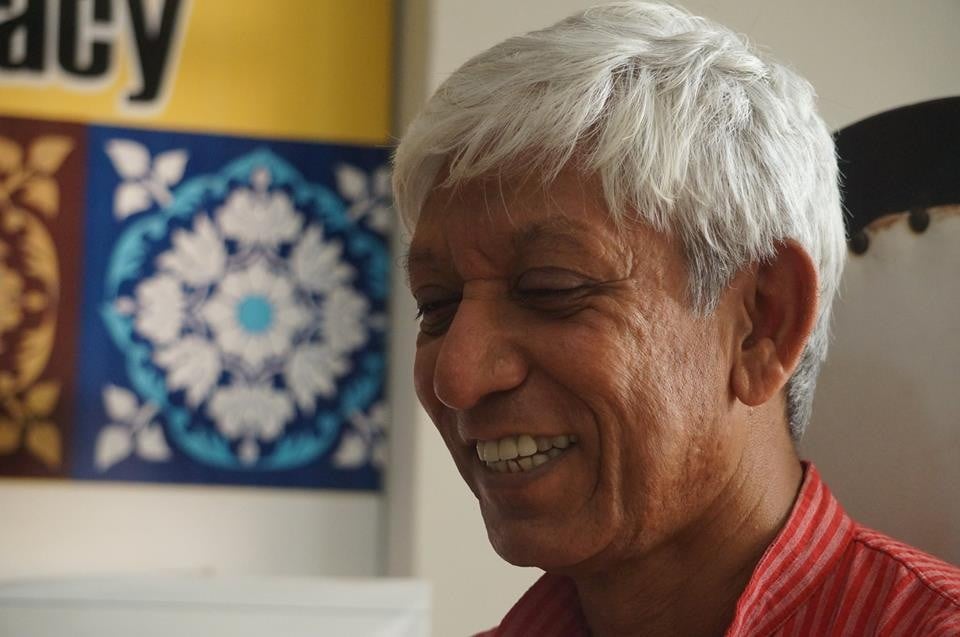

Ajmal Kamal, the man behind Aaj, is a well-read liberal scholar with a point of view of his own which he often expresses bluntly. In his magazine and by publishing many books on varied topics, he has daringly challenged the so-called ‘established’ views in the realm of Urdu literature. Despite rendering many essays, stories and poetry of other languages into Urdu, he had not written a book of his essays so far. Achi Urdu Bhi Kia Buri Shae Hai is the first book of essays by Ajmal Kamal which carries his trademark incisive analysis as well as his deadpan satire.

The book comprises ten essays of Ajmal Kamal that he has written over the years, and some of these essays he has shared on the internet and social media forums which ignited heated debates. The essay I would like to start with is titled Hamara Qaumi Khwab – Aik Jaiza. The esteemed author begins by showing us what ‘grand’ vision or dream we espouse for as a nation. Instead of looking at book fairs and literary activities organised by big publishing houses which are thronged by mostly the elite, Kamal refers to the locally organised literary events. Here, the books that are mostly bought are by authors like Naseem Hijazi, Khawaja Islam (of Maut Ka Manzar fame), Ishtiaq Ahmad etc. These writers conjure up a confusing picture of Islam and Pakistan, and thus indoctrinate the readers’ minds.

He points out the rise of gatherings in Pakistan in which Dastan-e-Ameer Hamza or Tilism Hoshruba are narrated for an audience that’s mostly elite. The themes of these dastans revolve around seizing the territories of infidels by force, and forcing them to accept Islam. There is ample spilling of blood in these dastans which quite a few Urdu litterateurs are patronising. The author make a valid critique on this aspect of dastans.

There are a few hard-hitting detailed book reviews on the works of Mumtaz Mufti, Muzaffar Ali Syed, Salim Ahmad etc. Tanqeed Ki Azadi, a book of Muzaffar Ali Syed, has been dissected with honesty and boldness. Ajmal Kamal has pointed out many a blunder and bias on the pages of the book. Quoting many passages from the book, he tries to prove that Syed Sahib uttered confusing statements about various literary personalities with a heavy dose of bias. He may be a well-read man but what he wrote suffers from many glitches owing to his far-right approach and outlook.

Mumtaz Mufti’s Alakh Nagri fares no better either. Here too, the author has exposed the sweeping statements and other so-called supernatural episodes which make a major part of this heavy tome. Mufti claims that the 1965 war against India was won due to the help of dervishes who were equipped with ‘spirtual atomic power’. The author busts many myths woven around the personality of Qudratullah Shahab and the supernatural powers he is said to have wielded.

In another interesting essay, Ajmal Kamal assails Syed Suleman Nadwi who had attacked Allama Iqbal on his book Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam. He was wary of Iqbal’s stance that only the parliament is the right forum to conduct ‘ijtihad’. Nadwi’s stance was that Allama Iqbal wasn’t much satisfied with his work Recontruction… as he was planning to revise it.

In an essay on Saadat Hasan Manto, Kamal pays tribute to him and notes that each great writer like Manto enriches literature and leaves his or her imprints. In terms of ‘asloob’, he believes Urdu fiction has moved ahead after Manto. If our readers still relate to the writings of Manto, it is due to the fact that a few aspects of our social life still resemble the times in which Manto lived and wrote.

The essays and detailed reviews contained in the book are of scholarly merit. Ajmal Kamal, the indefatigable editor of quarterly Aaj, has boldly pinpointed the need to re-assess the works of so-called giants of literature. One hopes the book will be widely read and discussed.