Abdullah Hussein regarded Bagh (The tiger) as the best thing he had written and there are strong reasons to believe that he may well be right. Udas Naslen, which has rocketed to the top or nearly the top position as far as the ranking of Urdu novels is concerned, is essentially episodic. When a novel is spread out over a big span of time, almost forty years in this case, it comes to resemble chunks of narratives or building blocks arranged side by side.

Bagh, on the other hand, has memorable continuity. Incidents gell together and generate each other, hurrying towards a denouement which is inconclusive and full of despair. The subheading of the novel is "story of a love". It can also be rendered as "a story about love" but certainly not as a "love story" which would debase it to some sort of treacly romantic fiction.

There are some remarkable scenes in Bagh but none more astonishing than the one in which Asad and Yasmeen, two young lovers, meet at night in a forest, with rain and heavy thunder in the offing. It is a lovers’ storm really, wherein two orphans or waifs, adrift in a world that would never care for them, cling together in a frenzy which is akin to hopelessness. The rain comes pouring down and lightening descends on the forest, like a sheet of burnished silver, followed by impenetrable darkness. They also hear in the distance, the roar of a tiger, a creature only heard and not seen, and perhaps as lost as the lovers.

From the very beginning, you sense that it is an affair bound to end in disappointment and the narrative becomes, in turn, an escalation and de-escalation of a wrenching anguish.

For all its excellence, Bagh never equalled the popularity that Udas Naslen enjoyed and still enjoys. The reason for it is simple enough. It had a head start. During the early 1960s, Abdullah Hussein shot into prominence like a nova. I still remember the excited manner in which Shaikh Salahuddin and Haneef Ramay told me that an unknown young man has written a splendid novel which would soon be published by Nia Idara, a publishing house owned by Nazeer Ahmad Chaudhary, one of Haneef’s elder brothers.

Their infectious enthusiasm set my pulse racing and off I rushed to see Nazeer sahib. I knew him well as I had done a number of translations for Savera, a literary magazine he published now and then. Without any preamble, I said that I also would like to have a look at the novel’s manuscript my friends felt so enthusiastic about. Nazeer sahib was kind enough to let me take it home and read it at my leisure. He also added that I should write a few lines highlighting its excellence. "We are going to put out a big ad in Savera," he said. "This novel is going to hit the headlines."

By the time I had read about fifty pages I knew I was in the presence of someone outstandingly talented. Abdullah Hussein had Western models in mind, Hemingway in particular, and his prose had a lean and mean look about it, so different from the prose one generally encountered. When the novel finally appeared, there were critics and readers who found its prose raw, unattractive and may be unidiomatic. I saw nothing wrong with it and still find it mystifying that there are people around who can’t reconcile with the fact that during the 20th century, Urdu’s centre of gravity shifted from Delhi and Lucknow to Lahore. Therefore, the language embraced fresh nuances and underwent climactic changes.

There are a number of incidents in Udas Naslen which catch the eye but the one I most keenly remember is the chance encounter between Naeem, the novel’s protagonist, and Mohinder Singh, his friend, in a graveyard in France. Both are in the army fighting the Germans during the First World War. The question which riles Mohinder is an old one, as old as organised warfare itself. Why should a man go and kill someone, a total stranger, who has never done him any harm? This conditioning to kill persons you have no quarrel with is disgracefully bestial. It has always haunted men’s mind.

Achilles, the legendary hero, who joined the Greek army to attack the city of Troy had second thoughts about his mission and said: "Why should I fight the Trojans? They have done me no harm. Never have they driven away my cattle or horses or spoiled my harvest."

That was almost three thousand years ago. In recent times, Muhammad Ali, refusing to go to Vietnam, echoed the words of Achilles, saying: "I ain’t got no quarrel with the Vietcong. No Vietcong called me nigger. I am not going 10,000 miles to help murder and burn other people to help continue the domination of white slave masters."

In the end, as Mohinder prepares to walk away, he says to Naeem. "Do you know why I come here? The persons buried here were decent and honest. This is what I feel -- their gravestones, their names, their dates. They did not die a dishonest death, like rats. I have faced that death. To each man his fate." There is no better denunciation of mindless bloodshed than this.

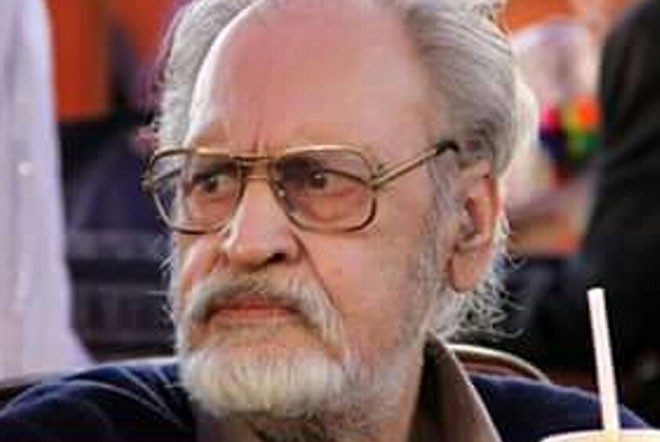

Abdullah is firmly entrenched in Urdu’s literary canon and cannot be dislodged. His short stories, not many, have a distinct flavour and his novellas like Raat and Nasheb remain unmatched. He is a realist. There is nothing mystical or philosophical in his fiction which is a mix of observation and imagination. His characters feel that there is something essential missing in their lives but exactly what? That is the unnerving issue. He once said: "Exile has its energy. What I am interested in is how people survive." Yes, they struggle to survive, daringly or submissively, until the inevitable happens.

Abdullah had a peculiar sense of humour, was a little eccentric and, as far as I know, a very lonely man at heart. That is why he insisted that his fiction was primarily about love. And the grace that resides in love is transcendence, as we know it, at its best. Nothing else but love will save the world, if it is to be saved at all.