South Asia has always had a very interesting relationship with its British monarchs

Years before she actually ascended the throne, the then Princess Elizabeth made a far reaching statement on her twenty first birthday in 1947, which still holds true. That April 21st, the young princess resolved: "I declare before you all that my whole life, whether it is long or short, shall be devoted to your service and the service of our great imperial family to which we all belong."

This is a promise she has never forgotten and has always kept close to her heart, and today, when she turns ninety, one must applaud her for her steadfastness, courage and almost extreme sense of duty and service. Today at ninety years old, she is the longest reigning British monarch [surpassing Queen-Empress Victoria last year] and has become the defining feature for an era.

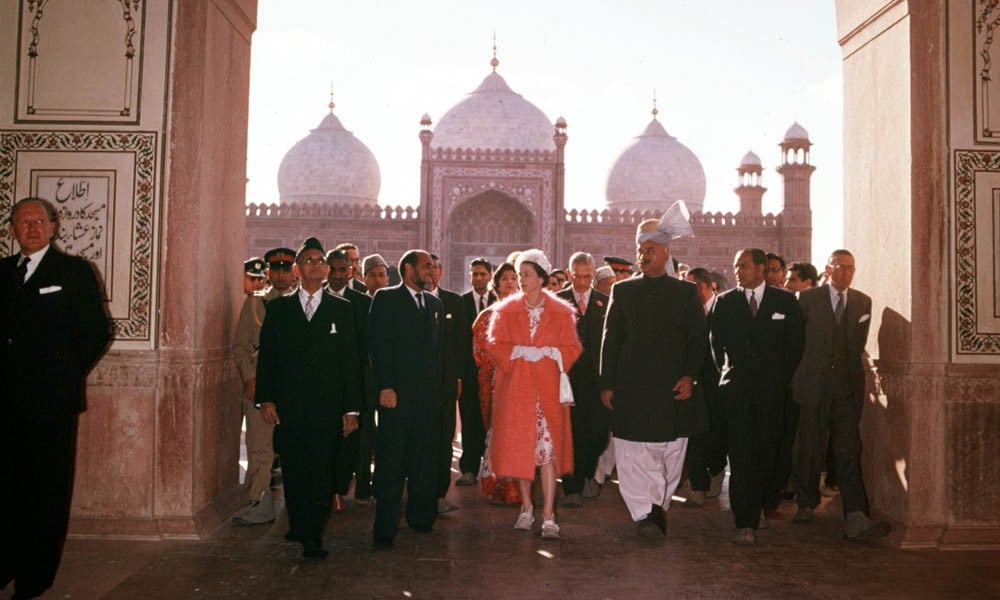

The Queen has had a very close connection with Pakistan. In addition to the hereditary link, she was even crowned as ‘Queen of Pakistan’ on June 2, 1953 in Westminster Abbey since Pakistan was still a dominion. Her coronation dress featured the symbols of Pakistan -- wheat, cotton and jute, as she ascended those royal steps to be anointed as sovereign. Later, she made two visits to the country, once in 1961 and another in 1997 at the fiftieth anniversary of independence.

In 1961, she was received with such gusto that nearly a third of Lahore’s population was reputed to have been out on the streets to welcome her -- a feat only comparable to Benazir’s return to the country decades later. Even in 1987, hundreds of thousands of people thronged to the streets to just get a glimpse of Her Majesty. It seemed that Pakistan might have become a republic but its love affair with its former monarch was continuing!

South Asia has always had a very interesting relationship with its British monarchs. Queen-Empress Victoria never actually visited India but she was so interested in the region that she appointed an Indian ‘Munshi’ and also learnt Hindustani. Despite the distance and difference, Queen Victoria remained much loved in India and at times her reputation in India was even better than what people thought of her in Britain. All monarchs since Victoria have visited India at least once and George V even had a spectacular ‘Delhi Durbar’ in 1911, continuing the connection with the subcontinent.

South Asia’s connection with Britain has been such that even when in the summer of 1947 millions were jubilant at the establishment of the two new dominions of India and Pakistan, the same millions were, almost paradoxically, saddened by the departure of the British, especially since many of the British in India had spent their lifetimes in the region and had achieved remarkable feats in the development of the country. In fact, when the transfer of power took place, the Union flag was replaced by either the tricolour of India or the flag of Pakistan almost everywhere except the highest flagpole in South Asia -- at Kalandchari in the Gilgit Agency. There, Subedar Jamshed Khan could not bear replacing the Union flag with any other since he could not accept that the British had ‘betrayed’ him and left! Such was [and is] the complicated relationship of the British with South Asia!

South Asia has always had a special relationship with royalty, something which continues both in India and Pakistan despite their republican outlooks over the last several decades. The existence of several hundred princely states meant that people not only had an elevated image of the distant British sovereign but also the more immediate ruler -- the Indian prince. Several of these princes were well ahead of their times and even shamed British Indian provinces in terms of development.

The Indian connection with royalty was mediated by the ancient South Asian concept of ‘Rajdharma’ which stipulated certain duties on the ruler which tied him/her closely with the welfare of the people. Professor Barbara Ramusack explains this concept as ‘offering protection to prospective subjects; adjudicating disputes among social groups including kinspeople, clans and castes; patronising religious leaders and institutions; and distributing gifts … to other cultural activities and social groups claiming kingly support.’ Under this conception the monarch is also seen as the ‘parent’ over the ‘children’ [the people], and as such a familial relationship is also established.

Several Indian rulers were good examples of Rajdharma and hence gained the life long love and devotion of their subjects. The continuing success of scions of royal houses in both India and Pakistan, in some ways, also relates to the heirs of the princely states following the precepts of Rajdharma today.

In the context of Queen Elizabeth II, while she might not have direct political power any longer, her deep sense of duty and devotion to her country and work set her apart as an ideal example of Rajdharma. With her age she can easily live a ‘royal’ life at home not doing anything; but she still visits the elderly, opens healthcare centres, attends football matches, and even replies to letters personally -- all out of a sense of duty and devotion.

At a time when people are jostling for self-interest, corruption is rife, and even after the Panama Leaks where politicians have no sense of proportion and ethics, the Queen at ninety shows us another dimension of public life. It is sadly a dimension democracy has not nurtured for us, but perhaps we can still learn it from her. Long live Her Majesty the Queen, once crowned Queen of Pakistan.