Bhutto’s symbolic significance as David of Pakistani politics pitted against Goliath of powers-that-be will remain

Every year April comes tinged with sad memories. In this sense April is the cruelest month. On April 4, 1979, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was judicially executed after a long-drawn out trial. I still remember the day wreathed in profound sorrow and hushed silence. Every one wore the saddest look imaginable.

Almost three decades later, ZAB’s daughter evokes the same mournful and sorrowful memory.

Yet Bhutto lives on in Pakistan politics beyond his grave. He lives on in slogans such as Jiay Bhutto, Tum kitnae Bhutto maro gae, har ghar sae Bhutto niklae ga (how many Bhuttos will you kill, from each house will sprout another Bhutto) shouted to hoarseness at the PPP rallies, now fast becoming a thing of the past. Beyond this, Bhutto lives on in symbolic fight between the contending notions of right and wrong, the powerful and powerless, democracy and dictatorship. The underlying narrative has been expressed in headline words such as ‘Leopard and Fox’, ‘Hussain and Yazid’. The last notion is loved by most people and was popularised by his equally sterling daughter, Benazir Bhutto, in her book. Thus Bhutto’s symbolic signifance as David of Pakistani politics pitted against Goliath of powers-that-be will remain. Furthermore, as long as unequal power relations exist in Pakistan, the appeal of Bhuttos will endure.

Bhutto introduced transformative trends in Pakistani politics. Beside his undeniable role in burnishing political consciousness of ordinary Pakistanis, he also made them outward looking. At his public rallies, foreign affairs were discussed as if they were affairs of the village next door. The holding of the first Islamic summit in Pakistan not only boosted the morale of a nation badly battered by loss of its Eastern part but also gave Pakistanis a place in the Islamic world and outer world. In an effort at his outward-looking politics Bhutto invited Col Qaddafi of Libya to address a public meeting at the Lahore Stadium (The stadium was named after him later).

Unlike other leaders of the Pakistan Movement, Bhutto was schooled in the anti-colonial style of politics. Though his knowledge of Marxism was limited to the Communist Manifesto, Bhutto developed a distinct political outlook which was informed by anti-colonial movement of the times and his own minority position within the Punjab military-dominated Pakistan.

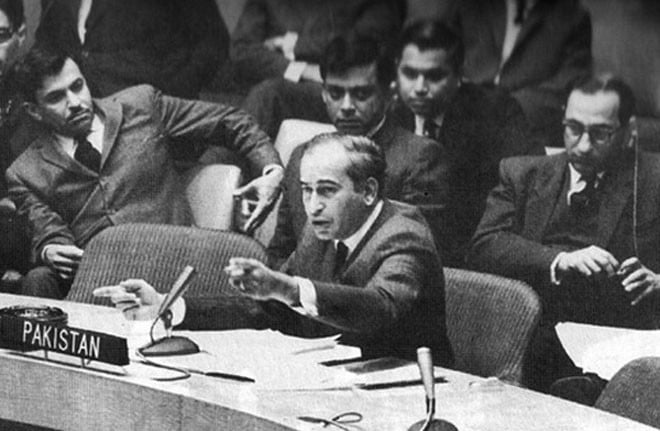

Bhutto’s anti-colonial politics was expressed in his admiration for Ahmed Soekarno, founding president of Indonesia, who was instrumental in forging non-aligned movement. Bhutto put his anti-colonial politics into effect when he took Pakistan out of the Commonwealth and Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation (SEATO) and Central Treaty Organisation (CENTO) arrangement of regional cold war. Even in his final days, he held onto his historically-informed view of conspiracies hatched against his government by superpowers.

In terms of his knowledge of foreign affairs he was peerless among the run-of-the-mill Pakistan political leaders.

He did not hesitate to hold forth on world politics when he met Western leaders. Long ago, in Glasgow, I happened to go to the one-time Prime Minister of Britain Edward Heath’s lecture on Europe. By sheer stroke of luck, I found myself seated next to Edward Heath’s biographer. While talking of Pakistan he lighted upon Bhutto. He told me that Bhutto in one of his meetings with Edward Heath launched into a long talk on how Britain should respond to new foreign policy challenges. Edward Heath, known for stubbornness and grumpiness and very much a man of his own, was not amused.

In Shakespearean language, Bhutto could see into the seeds of time and predict which one will grow or wither. This was confirmed to me by one of his close friends, Abdur Rahman Mohammad Babu, ex-foreign minister of Tanzania. Bhutto got Babu out of Tanzania when Julius Nyerere put him in prison (Bhutto also arranged his son and daughter to be educated in Lahore). Babu told me that one day Bhutto took him to a tour of Murree and told him about the shape of politics to come in the region. Bhutto predicted the fall of Shah of Iran and Shah Faisal of Saudi Arabia. This discussion took place in 1974. Bhutto’s predictions came true. Babu often used to narrate this as a proof of Bhutto’s deeper understanding of shift in global politics in those days.

Bhutto’s other lasting contribution was the inauguration of party politics in Pakistan as we know it today. Before Bhutto, politics was considered a preserve of the landed and scheming elites. By forming a political party, purely wedded to mass politics, he inevitably founded party political system in the country. He was shrewd enough to see that Pakistan boasted a large array of radical social movements which were disunited but looking for coordinated political expression.

In the PPP, he housed most of the left and social movement activists, who were enthused by a new political energy and social justice vision unleashed by Bhutto. Bhutto held the greatest appeal for the poor masses of the country. The poor and the down-trodden felt empowered in a way they had never experienced before. Bhutto was wont to say that he lived in every leaking and dusty house of the country. This pro-people and pro-poor politics has been the constant feature of Pakistani politics.

Even right-wing parties have had to copy this formula up to a point to stay relevant. My own father was one who made the journey to the PPP from Pakistan Democratic Party of Nawazada Nasrullah Khan. He often used to say his work within the PPP was the finest and the happiest period of his life. He never felt so politically elated, hopeful and engaged as he was when working as the office-bearer of the PPP in Chakwal.

For me, the memory of Bhutto is suffused with the sensation of a man in a hurry. For me, he remains connected with perpetual motion and political sensation. My very first memory of this dominant impression as a child remains of a Bhutto who whizzed past our house to address an election rally in Chakwal at the time of sunset during election campaign of 1971 or thereabout. The last image is one of his incarceration and judicial murder.

After that, there is total blankness interspersed with some flashes of hope ignited by his daughter. But the dominant impression remains that of a journey to nowhere after Bhutto’s tragic murder.