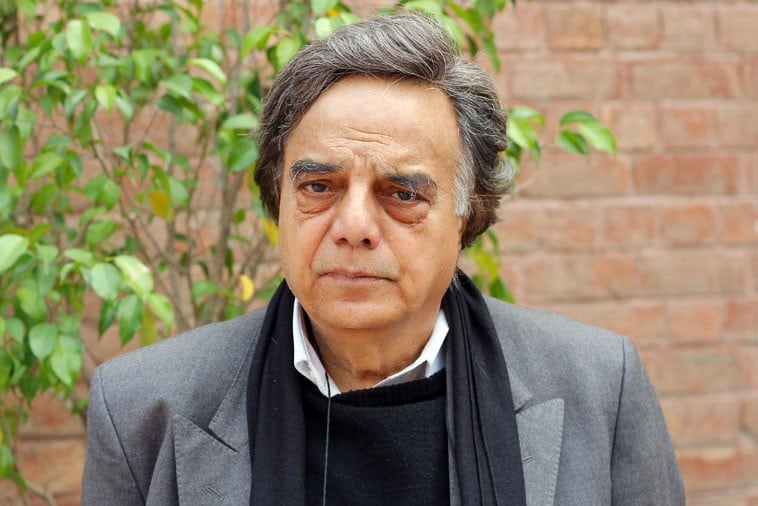

Nayyar Ali Dada is of the view that good lessons in architecture from the past can be a source of inspiration to recreate the future

The News on Sunday: Looking at architecture in Pakistan, do you think we have been able to forge or evolve an architectural identity of our own?

Nayyar Ali Dada: I don’t think we have been able to evolve an identity but we are struggling to find one. The awareness of identity was not there because we inherited a country where we did get architecture of our share, in our cities, the buildings that we had built in the British period and before and after. The modern architecture took off in or around 1960s or so.

Like influences from the outside in the shape of technology, environment and everything around us, in things and ideas, we did pick up a mocked up modernism unsuccessfully. But whatever we had of our own, the sense of continuity of history, was disturbed by colonialism. And then nothing was reborn immediately.

Now we have somehow found ourselves in a tremendously complicated and confusing situation -- of what is good architecture. Everything that was modern, followed modern technology was considered good, and everything that was old and old-fashioned was rejected. That was the basic formula. But we found that modern architecture that we chose above traditional solutions was not delivering much.

Now we are realising that, in architecture, a sense of continuity is important -- we must re-invent the future or chase the future but we must not reject the past altogether. That does not mean we should copy or mimic the past but learning good lessons from the past that could be validated or could be a source of inspiration to recreate the future.

Read also: "We need to democratise architecture"

TNS: What does an architect really do and where do the social and cultural aspects fall in his scheme of things?

NAD: The architects are given the task of doing a project. It is very different from just a pure professional and technical assignment -- that you design a building, build it safely and it should do its functional job. It is also a part of culture because the architects are dealing with the landscape of the city and not just individual buildings. If they are not aware of the city at large -- the city centre, the squares and streets -- that is what creates a hotchpotch. Then you see next to the Lahore High Court a lousy State Bank building, both existing as bad neighbours.

We have created a lot of hotchpotch in terms of architecture. We have not shown respect to the old buildings. The new buildings don’t show respect to the environment or climate or culture of this place. It is a very tough task. If you look at a hundred new buildings, only one or two are okay. The reason is that there is no overview of architecture in urban planning; it is done in small bits and pieces.

Urban planning is the poorest part, beginning with land use. We are making colonies over good agricultural land. Then we have [no sense of] commercial areas. In Lahore, we have all industries are in the housing areas of the Walled City, producing toxic gases. There is no such thing as land use. Now we have an organisation by the name of Urban Unit. But, so far, our feet are not on the ground.

TNS: Where does design fit in? Is architecture a field that allows for pure creativity and indulgence like other forms or is it subservient to functionality?

NAD: It has to be a balancing act. If you produce buildings that are functional but dull and boring, it does not work because architecture is also a visual art. We are responsible for creating a new landscape of today and tomorrow.

The issue of aesthetics is more about the bad taste of the consumers and the architects too, but the bigger share goes to the consumers because they dictate a lot, asking for Greek columns in their buildings. Bad taste is a problem with the entire population. Good aesthetics is a part of civility. In fact, art appreciation starts at a very young age.

TNS: Awareness begins with seeing good architecture in public places. Shouldn’t we blame the state and government for not doing much about it?

NAD: Certainly. Governments’ contribution has been a disaster because the selection is done by bureaucrats, mostly invested with bad taste. The politicians’ decisions too are invariably a victim of bad taste. They are not cultivated very well. That is why you see ugly buildings coming up which have no relevance, either to the past or to the present.

TNS: Tell us a little bit about Alhamra?

NAD: I have tried in examples like Alhamra which are not a Western take-off and nor are they a copy of Mughals [to show that] it is possible to find an expression which belongs here.

When I walked through the Mall Road after taking up the challenge of making a very important building on that road, I tried to learn from what had been done well in the past and I found remarkable buildings of Aitchison College, the Lahore High Court and others. I thought that if the British were able to do that, let’s try to do something good as well. The budget was less than shoe-string, so, we developed it in a simplistic manner by just using the local materials and keeping in mind the demands of modern technology. I am not trying to say that I have found the solution but it may be, comparatively speaking, a building which is useful, both in terms of function and as a piece of identity.

TNS: How big is the constraint in the shape of a client’s bad taste, of capital dictating the taste and design?

NAD: Very big. There are two areas: one, the private sector that you can build for; the other is the government sector. Government sector has a problem of bad taste. Unfortunately, in the private sector, you do find people of taste but rarely. Most commercial clients, the developers, are the biggest disasters. They copy the Eifel Tower and Trafalgar Square. It’s a shame that we are so impoverished that we copy and paste that sort of a thing.

Our fashion industry and our fashion designers in lawns etc. have done some very smart modern designing. It is taken from ajrak, from aroosi background, from our customs. They have innovated on that and they have glorified tradition and captured modernity. Architecture needs that sort of a challenge where you can go ahead with the times and still keep the legacy on.

TNS: Can tradition and modernity exist separately in architecture?

NAD: This debate is very old now. The accepted reality is that the only correct philosophy is that of pluralism with a sense of freedom. Dogmas won’t work now. Sticking to only one of the two approaches is wrong. Either can come in as long as it delivers a sense of good design with a sense of inventiveness. We have to invent the future, with a sense of place, time, culture and the users for whom we are making it. It is a difficult task but that is the challenge. And we have not caught the threads so far.

TNS: In terms of masonry and other workmanship, do we face a constraint?

NAD: I don’t know of any polytechnic institutions churning out qualified plumbers, brick layers, and electricians. Like paramedics lacking in the hospitals, we too lack the middle strata in our construction. The skills are very poor.

TNS: It seems that one thing the architects would like to associate themselves more with is conservation. And it appears that conservation has consumed talent.

NAD: Conservation is an important facet of architecture. But conservation can’t become a style or a fashion which it has become.

Cosmetic copying is injurious. The solution lies in looking at urbanity of the whole city first, then areas and finally individual buildings. Architecture is more than just individual buildings. It is also looking after the overall character of the city. What is happening is piecemeal and it lacks character. There is no depth in it; it is facile.

There are exceptions though, as I mentioned fashion, which show that it is possible to deliver both. Same is the case with music. There is the example of Nusrat Fateh Ali who has taken tradition to the skies. If you take architecture as a visual art, we have the same sort of challenge. Despite all the confusion (because it is not easy to pinpoint what is the right philosophy), the one positive thing about architecture that I would like to follow is the sense of freedom and not be bombed by dogmas. I would follow principles which have always been correct; they were correct in the past and will be correct today and tomorrow. The criterion of a successful architecture is that it is not the critics’ choice but the users’ choice that is important. That is also an important facet.