Pakistan’s journey from a "not free" country to a "partly free" country is not so impressive

A recently released document "Freedom in the World-2016" released by the Freedom House depicts a grim picture of human freedom in a turbulent world. Epilogue of the report narrates a depressing reality "the world in 2015 was battered by overlapping crises that contributed to the 10th consecutive year of decline in global freedom".

This steady fall of human freedom is a least debated tragedy of the so-called modern and civilised world. Relishing material gains for a small proportion, the world often glosses over the shackled minds and muffled voices of the hapless billions strewn over a larger part of the globe. How lack of human freedom distorts societies and impedes their overall productivity is a proven reality and an undeniable fact. Freedom of thought, expression and organisation has long term dividends for human societies and that is often scuttled for short-term whims of autocratic and authoritarian regimes.

Pakistan has been marked as "partly free" on the global ranking of freedom. However, it has been denoted "not free" on the freedom of internet and press. Since 2009 the country improved its ranking from a "not free" country to a "partly free" country and since then maintained the same position. However, its score on the scale of 1 to 7, best to worst respectively, has stagnated at 4.5 during the past seven years.

Pakistan has a blotted history of stifled civil liberties. Protracted dictatorial regimes trampled civil liberties for long spells of our history. Right of expression and organisation remained a major casualty during these eras. The constitution was trashed for several years and the country was ruled under illegally promulgated legal framework orders; a handiwork of constitutional mavericks.

Defilement of constitution was so comprehensive that every disagreement was equated with treason. Press and other means of communication were ruthlessly regulated. A sanitised media effectively precluded growth of a civil society that could create and subsequently dilate the sphere of civil liberties. In a stark contrast, unfettered proselytisers and obscurantist elements enjoyed freedom.

The incumbent Chief Justice of Pakistan also expressed similar feelings in his recent speech. Justice Anwar Zaheer Jamali, while addressing a ceremony organised by the Endowment Fund for the Preservation of Heritage, said "it is unfortunate that due to the consecutive imposition of martial laws not only a true democratic system could not be established in the country but also the people remain ignorant of the real spirit of democracy. The country faced lawlessness and disturbances and the undemocratic forces flourished due to such undemocratic rule."

The decade of 90s witnessed frequently scuttled eras of quasi democratic regimes. These narrow apertures offered some breathing spaces to a lackluster society that was asphyxiated for decades. Civil liberties found a toehold and a nascent civil society started taking baby steps. A relatively free press gained momentum. Tone and treatment of news and views took positive strides and the new media emerged as a cornerstone of an incipient civil society. Women rights, minorities’ issues, grievances of provinces and human rights violations by non-state and the state actors found new avenues of public discourse. In a country where voicing for even constitutionally guaranteed rights is insinuated as western agenda, these limited spaces are of paramount significance.

The unconstitutional era of Gen. Musharraf marked a departure from previous dictatorial regimes when civilian domain was allowed to function as against dark days of Gen. Ayub and Gen. Zia who gun-fenced every inch of public space. Electronic media got new impetus and bolstered civilian freedom to a considerable extent. However, Musharraf’s enlightened moderation buckled under the lawyers’ movement as he tried to curb media but it was too late by then.

With the onset of a new spell of democratically elected government in 2008, civil society and civil freedoms got a shot in the arm. However, all these civil liberties were not a unilateral charity by the government to the society. In fact it is in the own interest of elected governments to strengthen civil society for longevity and stability of their own governments.

A free and dynamic civil society is lynchpin of any democratic dispensation. Unfortunately, during recent years, all these meager gains of civil society have been systematically reversed. In the garb of regulation, a wave of hostility has been unleashed against civil society organisations. Sweeping statements have been flippantly issued to demonise civil society, at times without making any distinction. In absence of clear guidelines and a mutually agreed institutional arrangement, various government functionaries are taking impetuous actions without any substantial evidence and premeditation.

While certain segments of society are free to convene rallies and huddles and openly proselytise hatred, paradoxically civil society organisations requires no objection certificate to convene forums to discuss innocuous development issues of public interest like education, health and constitutional rights. Decoy of security is being exploited to justify this hysterical and egregious attitude. A sane, dignified and civilized approach would have served the purpose in a far better manner. Rather than gathering information through multiple veiled sources, a more transparent and decent approach could be adopted. Intimidation and vilification of civil society organisations and workers would only widen the crevasse between the two important pillars of society. Ultimately it will deprive millions of impoverished and forsaken citizens of valuable support that they are receiving through non-governmental organisations.

The government should not ignore the fact that sapling of democracy still has shallow roots and it needs all kinds of props to endure frequent onslaughts. Fragility of democracy and civilian forces has been once again exposed by the recent episode of Gen. Musharraf’s ceremonious departure from the country deriding all constitutional stipulations and dampening all desires of the government and opposition. Such a frail democratic dispensation ought to forge strategic alliances and cultivate conciliatory relationship in society rather than vexing its potential allies.

Civil society and democracy are inextricably intertwined and mutually complimentary. By undermining and crippling civil society, the government is actually shooting in its own foot. Apart from support for underpinning a delicate democratic system, the government also needs civil society arm to bridge a yawning development gap in the country.

Pakistan miserably failed on almost all critical targets of millennium development goals. Our health and education indicators are ignominiously poor. On human development index, we are ahead of only Afghanistan in South Asia. Our performance is dwarfed by all other countries in the region. The newly-launched Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are even more comprehensive and require greater synergies and collaborative efforts between the government institutions and the civil society if we have to save national grace in the international community.

Constrained by myriad limitations and flaws, no government can alone accomplish ambitious human development targets without an active support of civil society. Apart from resources, it also requires meticulous planning, coordinated initiatives, extensive outreach, participatory monitoring and critical feedback. Unfortunately public sector’s capacity has been circumscribed by several deficiencies.

Inefficiency, corruption, nepotism and a pervasive lethargy has plagued public sector and it has lost its mettle to extend essential basic services and constitutionally recognised rights to the millions of deprived citizens. Private sector is unbridled and recklessly flouts rules with complete impunity. Colossal unmet needs in social sector cannot be delivered by government alone in these circumstances.

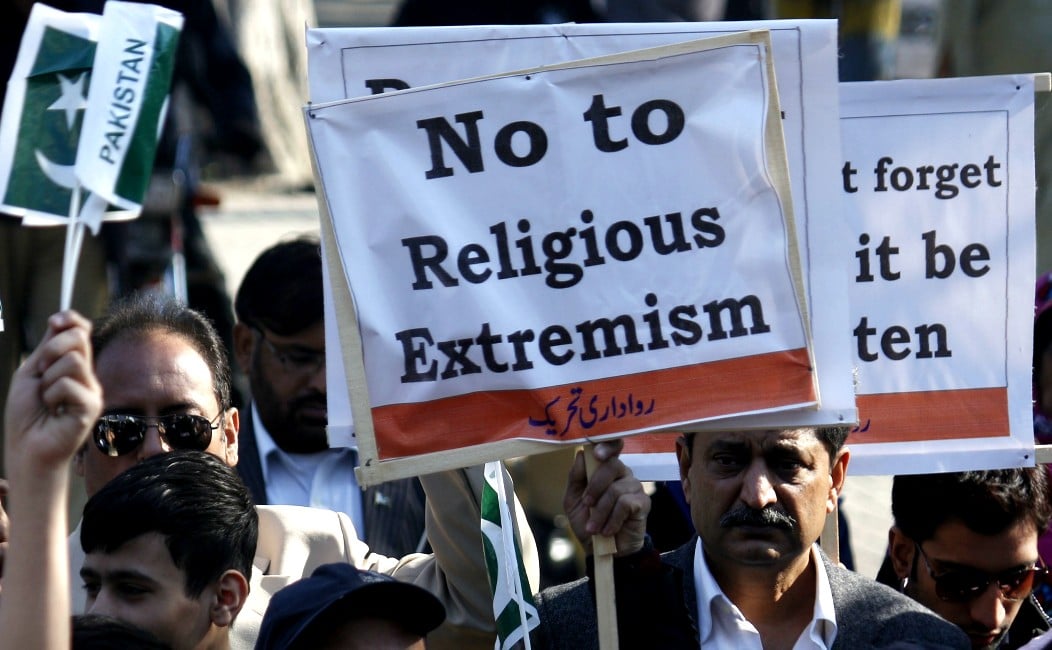

Another daunting challenge is infiltration of virulent extremism into every street of Pakistan. The government’s weaponry can eliminate terrorists but erasing extremist ideas infused in the society would be an arduous slog. Minds of generations have been poisoned and civil society can provide invaluable support to extricate society from this deep quagmire.

Civil society in Pakistan had been consistently resisting the elements who had been coddling extremism in the name of national interest during the past decades. This lack of sapience on part of the ruling elite has brought the fruition of barbarity and bloodshed in the streets of Pakistan. Millions of indoctrinated and distorted minds cannot be disinfected alone through the administrative actions of any government. It is in the own interest of state institutions to fortify civil society to surmount this complex and strenuous challenge. A recent example is civil society’s support to the government to withstand pressure of an enraged religious lobby against the women protection law in Punjab.

In fact there are more reasons to respect and support civil society than treating it insolently. The country does not lack legal instruments to regulate administrative matters of the non-profit sector. If laws and rules need any improvisation, it can be negotiated without civil society stakeholders getting freaked and resorting to a witch-hunting spree. Freedom and respect of civil society is considered as a touchstone of civil liberties in civilised societies. A functional and a vibrant civil society will pave the way for rule of law, a satisfied citizenry and a sustainable democracy in Pakistan.