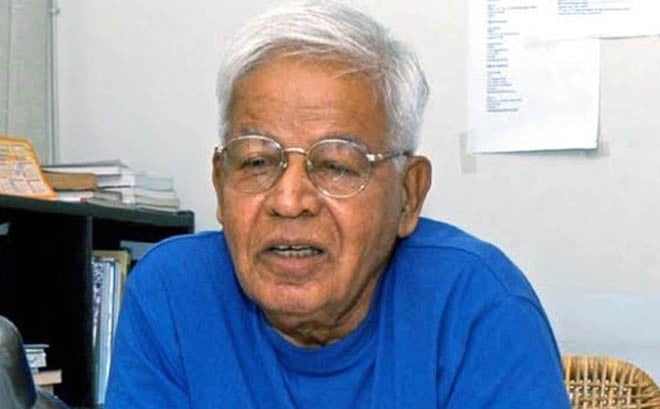

Veteran journalist and human rights activist, Husain Naqi, looks at the student politics in Pakistan in a historical perspective, stressing on the need to lift the ban on student unions

Veteran journalist and human rights activist, Husain Naqi, has been an active student leader. He was president of Karachi University Student Union (1962-63) when he was rusticated from the University for protesting the removal of three Baloch students. He was General Secretary National Students Federation -- 1960-62 and was General Secretary Students Union Islamia College (Civil Lines) Lahore -- 1959-60. Naqi firmly believes that democratic process cannot be strengthened without students being allowed to form unions.

Excerpts from the interview:

The News on Sunday: How do you look at the students’ movement at the JNU in terms of students awakening? Do we have any lessons to learn from them?

Husain Naqi: The lesson to learn is that democratic development cannot take place without the students being organised in a union. There was a ban (in Pakistan) on student unions during the military regimes, of particularly Ziaul Haq. Since then there has been a decline in younger people joining politics with a background in a democratic organisation or in a democratic setup. At least during the first military regime of Ayub Khan no ban was put on the student unions. I myself was elected as president of Karachi University Students Union after a ban was lifted against political parties.

Our organisation, National Students federation (NSF), had also been banned as a political organisation. But there was no ban on student unions. Only the system of (student union) elections was changed when there was a ban on political parties. From 1958 to 1963, student unions were elected indirectly because they were trying to promote a system of indirect political process. So, a council would be elected from amongst the students from different departments and they used to elect union leaders.

That was, you can say, a prototype of the democratic setup and the budget of the union was debated perhaps better than how it is debated in some of the provincial assemblies.

During Ziaul Haq’s period he tried to impose Jamaat-e-Islami’s student wing on the students. That was the only organisation which was not banned -- Islami Jamiat Tulaba.

There was no freedom for others to organise themselves or hold elections for the student unions. And subsequently, unfortunately, the superior courts also banned student unions. When the last government of the PPP was established and Yousuf Raza Gilani was to become the prime minister, he asked Dr Mehdi Hassan what would he like him to do? Hassan said that he should remove the ban on student unions. Gilani had promised to do so. He talked about it in the parliament as well but was unable to withdraw the ban or allow them to hold elections of the student unions. Because the establishment in Pakistan is opposed to democratic development and it is one of the reasons that they are scared of students getting organised.

Actually, we were ahead of the other countries in South Asia in a way. In Pakistan, in both the eastern wing and the western wing, student unions were the leading bodies which strived for the restoration of democracy and an end to martial law. Ayub Khan’s martial law ended because of the students struggle. In East Pakistan also, there were very strong student bodies and some of the present-day leaders of the then East Pakistan are former student leaders. This kind of activity one does not find in India. Except for a couple of years of Indira Gandhi’s emergency rule, there has been a continuity of the democratic system in India.

Although the students did participate in protests to end the emergency rule against Indira Gandhi and restoration of democratic process, the student unions in India today are rival bodies with secular ideas and with religious ideas. I know this for certain because I visit India occasionally. In Aligarh and Osmania and some other universities there are organisations which have a religious bent and they are dominating the electoral scene at the university level. In the north, there are mostly religion-based organisations, such as Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP). That is the BJP-RSS sponsored body. Then there are progressive organisations; there is All India Students Federation and there are some other organisations also which are secular and progressive.

Read also: One-union show

TNS: What role did the student politics play in the political awakening in the country, especially since the early 1950s?

HN: The movement to support the establishment of Pakistan was led by the students, by Aligarh Muslim University students in particular. Muslim League was not a well-organised political party. It was the students of the Aligarh Muslim University who came to Pakistan in 1946 and campaigned for Muslim League candidates. They also went to the NWFP and other parts of the country. In East Pakistan, they also had some role because many students in Bihar and East Bengal were studying at the Aligarh University and they campaigned for that. Actually, the then Vice Chancellor, Dr Ziauddin, a renowned mathematician of the sub-continent, personally campaigned and other academics were also involved.

After the creation of Pakistan it was the students movement both in East and West Pakistan who were leading the democratic movement against authoritarian rule. In West Pakistan, the first democratically elected government was removed from power. In NWFP, the youth leadership of Khudai Khidmatgars, most of them were student leaders of their time. They were coming up and challenging the Muslim League.

In Sindh, because the capital was in Sindh, the leading student organisation was a Left organisation, Democratic Students Federation (DSF). In Rawalpindi, Abid Hassan Minto was a member of the DSF. There was a progressive Left student movement in Sindh and the leadership came from different parts of India: from Hyderabad Deccan, from Allahabad, from Lucknow. Some of them were also from Punjab like Dr Ayub Mirza and several others. They formed the leadership and then they formed a national organisation. The ruling Muslim League was so scared that it saw to it that this combined organisation, the All Pakistan Students Organisation (APSO) in which various students organisations had merged, was banned. And, subsequently, NSF, created by the former pro-vice chancellor of Aligarh University and the then Vice Chancellor of Karachi University, ABA Haleem, organised NSF to counter DSF but later NSF leaders had agreed to include us, a couple of former DSF supporters.

TNS: Student unions in Pakistan have braved the martial laws in the 1960s. How do you evaluate their struggle?

HN: Actually, when martial law was imposed in 1958, apart from political leaders, there was a widespread arrest of student leaders belonging to DSF and belonging to other organisations. At that time they were from the NSF.

So, both in 1960 and in Ziaul Haq’s period journalists were arrested, except for during the Musharraf period when there were no arrests of student leaders because there was already a ban on student organisations. Journalists had also joined the struggle for the restoration of democracy.

At one time there was a letter from Ziaul Haq which said that the administration was directed to ensure that a combined organisation or coalition of student leaders, journalists, and trade unions should not be allowed to be formed. I was myself arrested and sent to the Lahore Fort where they had established their torture cells to torture the youth and workers of the Pakistan People’s Party. For the first time, females of the Pakistan People’s Party were kept in the torture cells of the fort.

We were arrested under the Official Secrets Act. The letter from Ziaul Haq had been sent even to the tehsildar level. They claimed that the letter had come from the Soviet Union through Mazhar Ali Khan and that he gave it to me and I mentioned it in theViewpoint. This is so absurd. I was bureau chief in PPI at that time. Somebody must have sent it through the mail and I used it in my "Lahore Diaries" in Viewpoint. Many students were arrested in Karachi, such as Mairaj Muhammad Khan and Fatehyab Ali Khan.

Before that, in 1963 there was a movement against the three-year degree course for students. Subsequently, the government had to accede to our demand. I came to know through teachers that the three-year course was proposed to raise the fee and to restrict the number of students in higher education because when they passed out there was no opportunity for jobs.

TNS: How do you think IJI’s influence increase in academic institutions, such as the Karachi University and the Punjab University?

HN: Ziaul Haq allowed only the IJT to function despite the fact that it did not have much support. Bhutto also created factions among students of People’s Student Federation (PSF). He also created factions among trade unions and labour organisations. Bhutto divided the PFUJ with the support of Jamaat-e-Islami.

TNS: Why are students so de-politicised today and what has this led to in Pakistan’s politics?

HN: Because they are not allowed to operate. If students are allowed to form unions and if there are elections students will become active politically. As they say about the ban on kite flying, arguing that it causes deaths, in the same way, they say that if student unions are allowed to operate there will be armed clashes. They should ban arms instead of student unions.

Whatever happened at the JNU has further strengthened the student unions. That had a very positive impact in India. They got the support from every province. Some 40 universities observed sympathetic strikes with the JNU.