A detour into a brief history of the relationship between the Pakistani state and student political groups to caution those fighting for civil rights in India -- to learn from their own past and also from Pakistan’s history

The recent events at the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in New Delhi have invigorated a section of India’s civil rights activists and scholars as they have protested the high-handedness of the Indian state’s attacks on one of the country’s most prestigious public university.

The events that led to the arrest of the elected leader of the student union, Kanahiya Kumar (a member of the All India Student Federation (AISF) which is linked to the Communist Party of India (CPI)), were related to a programme to commemorate the execution of the Kashmiri activist, Afzal Guru. Guru was sentenced to death for the part he played in the attack on the Indian parliament in 2001. Many believe that Guru did not receive a fair trial and the assembly at JNU spoke against the death penalty and there may have been slogans raised in favour of Kashmiri self determination.

The authorities with the backing of the BJP-supported student group on campus, ABVP (Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad), took Kumar into custody on charges of sedition, alleging that his speech at the Guru rally was anti-state. Later, two other students were arrested, who remain in custody, while Kumar has recently been released on bail.

Internationally, there has been widespread condemnation on this move by the Modi government and JNU has been projected as a major stand against the curtailment of academic freedom and civil rights in India.

In focusing on JNU as a special case, sometimes it is forgotten that the intrusion of the state into academic life in India has a more complex history. It is indeed true that the BJP government has been replacing the higher administrators at federal and provincial universities with its own chosen people. Among other appointments, it has put a party loyalist as the director of the Teen Murti Nehru Memorial Library, one of the most prestigious research institutions in India. There has also been an ongoing harassment campaign against Dalit students at different universities; this has, at least in one case, led to the death of Rohith Vamula at the University of Hyderabad earlier this year.

However, these changes and the intervention by the state forces are not new. The anger of academics, civil rights activists and liberal politicians on the recent happenings at JNU and at other campuses is justified, but the fact remains that such disruptions of academic life have consistently occurred in India. Where there have been concerns about the integrity of the nation state, security forces have regularly entered and occupied universities in the Northeast of India or in Kashmir (and other places).

Similarly, lest we forget, in the late 1960s the Maoist-influenced Naxalite revolutionary movement was joined by a number of urban intellectuals and became popular among students in Kolkata colleges. In early 1970, presidential rule was imposed on West Bengal to combat the internal threat of a communist uprising and, subsequently, through a militarised state action, thousands of activists and innocents were tortured, incarcerated or killed in police encounters. By the time the movement’s force subsided in 1972, the region had lost some of its best and brightest.

What needs to be remembered is that the violence inflicted on the students, workers and peasants in West Bengal was not by a right wing religious party, but under the orders of a government of a secular nationalist party i.e. Congress.

Read also: "They should ban arms instead of student unions," says Hussain Naqi

The point that I want to emphasise is that the state, irrespective of its ideological bent, has a near monopoly on carrying out violent acts against whoever it considers its enemy, internal or external. Also what needs to be remembered is that India has a stable democratic tradition with no history of military takeovers. It also has a strong civil society, some excellent research universities that have exceptional scholars teaching in them, a history of Left and liberal grassroots activism for democratic rights and an independent judiciary. Even with this history, JNU is not an exception.

One fear that the events in JNU do bring forward is that the practices that the Indian state follows in "trouble" areas or in peripheral parts of the nation state (the occupation by para military forces of universities, the using of sympathetic student groups to silence dissent, the threats given to faculty members who have politically oppositional views) can now be used in more prestigious public campuses in India’s major cities.

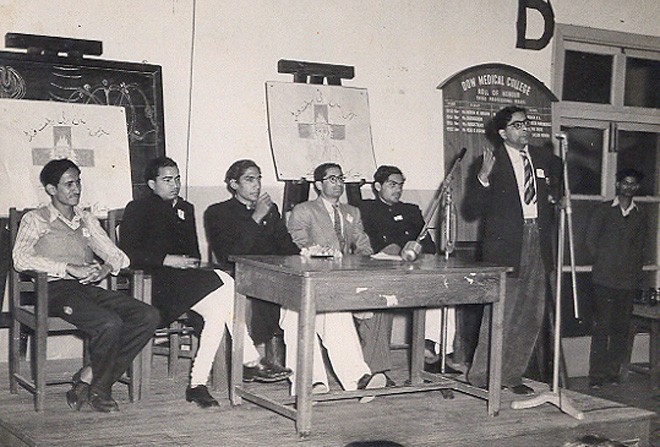

I raise this fear in light of a reading of Pakistan’s past, where since the 1980s the country has witnessed the ‘occupation’ of its Universities by security services and the curtailment of academic freedom through the intervention of state authorities on a regular basis. Like India, there is a long history in Pakistan as well of student activism and struggle for justice; one recalls the student movement of 1952, the first student movement against the Ayub regime in 1962 and then the participation of students in 1968 struggle that ended in Ayub’s removal. Further, various Pakistani governments, whether civilian or military, did not hesitate to use force to clamp down on student unrest, whether in Dhaka in February of 1952 during the language protests or in January 1953 in Karachi, leading to several deaths in both cases. One should also remember the horror of the night of March 26, 1971 when many Bengali intellectuals, academics, students, were killed in Dhaka University by Pakistani forces.

Yet, the systematic banning of student unions by the Zia regime in February of 1984 was unprecedented in Pakistan’s till then turbulent history with its educated youth. The dictator’s aversion to political parties created opportunities for ethnicity based student groups to be formed. Some of these may have had state sponsorship to create factionalism within more ideologically-motivated student parties. In the absence of student elections and unions, the implicit encouragement of certain religious and ethnic student groups created rivalries on campuses in Karachi and elsewhere.

In the late 1980s, this led to extreme intra-group violence at universities. The state watched while mayhem reigned for a while and then sent in its para military forces, the Rangers, to control the situation, much to the relief of parents and students alike.

In retrospect, one can now see how the situation may have been manipulated to create space for the security services to enter the colleges and universities. Those student groups and affiliated political parties may now regret the violence they had unleashed on each other for very small gains, but a long-term damage has occurred in the academic atmosphere of Pakistan’s universities. They have become securitised camps that remain under an unparalleled surveillance system (this is even before than the recent threat by terrorist groups).

Once the security services entered the premises, in one form or the other, they have maintained their presence. The Pakistani civil society was weak in the late 1980s after being brutalised by a harsh military regime for a decade, but the spectre of that period still haunts the country and university spaces still remain inaccessible to many.

My detour into a brief (and incomplete) history of the relationship between the Pakistani state and student political groups is to caution those fighting for civil rights in India to learn from their own past and also from Pakistan’s history, where under the pretext of law and order universities can become barracks overnight.

The heroic unity to defend and safeguard the right of free speech, the right to assembly and of civic freedom by JNU students, faculty and staff and the international solidarity network is impressive, but to sustain the struggle there always remains a need for extra vigilance.