An important book by Dr Shaukat Mehmood and Shamim Shaukat on European art history in Urdu

Every year, the admission test in an art school turns into a trial of sorts. The medium of exams at most institutions is English. This becomes a dilemma for various talented applicants who have great potential for studio practice but limited knowledge of English. The selection board is faced with a conflict -- it can either bend the rules to make space for students who are unable to pass the English test or to keep following the rules and deprive them of art education.

Everybody knows well that not performing well in the English language examination has does not mean that a person has a low level of intelligence. Some of these applicants are extremely eloquent and incredibly articulate in Urdu. Due to our class based system of education, unfortunately the ability to grasp, attempt and express in English language depends upon your social stature. Being well versed in English is a tool that helps you get into the circle of power.

In the world of art education, the situation is reversed. Here, the most dominant component comprises studio-based courses. So a student may lack English language skills and yet be ahead of his peers in the class. Thus in the art schools, both English and Urdu are used to familiarise students with art history and theory.

But we still require a sufficient body of literature in Urdu which can help more students across the country to access art history. Responding to this need, Dr Shaukat Mehmood and Shamim Shaukat have written a book on European art history in Urdu. Maghrib mein Funn-e-Mussawari ki Tehreekin is published by Pakistan Writers Cooperative Society Lahore, and offers an introduction to the basic concepts and background of Western art.

One may argue about the divide between West and East when it comes to art and its history, but the fact remains that a major discourse in our art schools draws heavily from European and North American art. And students are expected to learn world art history which in reality is Eurocentric. The problem is how to comprehend European art in a language that is far removed in time and region.

Both the authors have managed to translate, transfer and convey the essence of mainstream art in a vernacular that is more accessible and approachable. They have started with the history of Classicism, Byzantine, Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque, Rococo, Pre-Romanticism, Neo-Classicism periods and enlighten the readers with the currents of modern movements such as Cubism, Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Realism, Barbizon School, Naïve Art to Impressionism, and many others till we come to the last chapter, the Super Realism.

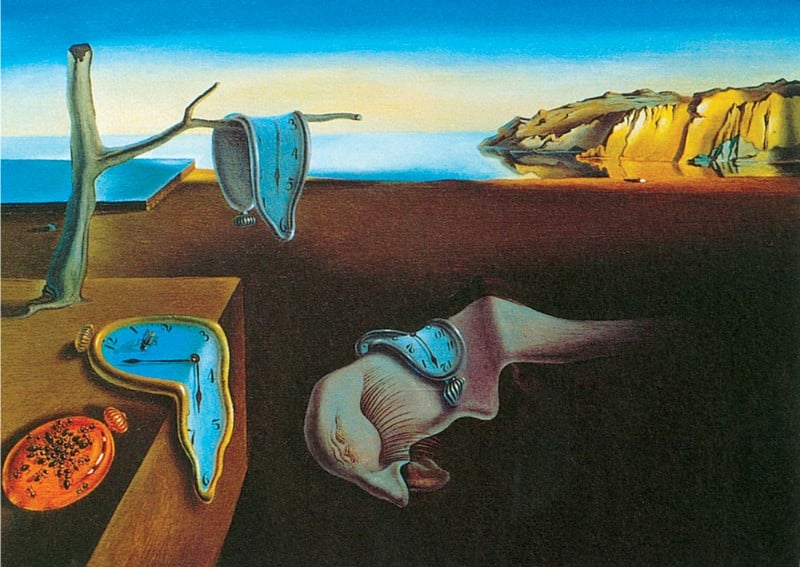

The most significant element of all these chapters is that these provide a thorough yet clear description of artists and art movements across the ages. Each section discusses the background, important points and significant artists of a period or style, along with reproductions of art works, so a reader can also get the visual information on the subject. But it is not limited to narrow or formal boundaries of different movements; for example, in the chapter on Realism, the authors add by indicating its variations such as Social Realism, and Marxism and by invoking the link of Realism to writers such as Balzac and Flaubert.

This whole picture is essential in our context because, besides not having sufficient knowledge of these art movements, people in general are not even aware of their connections with other forms of creative expression and changes in society. So a book in Urdu serves the purpose of demystifying the language of art, which if it’s in English or is written in a totally undecipherable diction becomes a barrier between art and people.

In a sense, the language divide is a reflection of the separation between art and literature. On many occasions, Intizar Hussain had recounted how the writers and painters were meeting and conversing during the 1960s. Once the artists’ works started to sell, they moved away from that circle while the writers remained at their coffee houses spending hours discussing literature. Compared to the past, artists are making commodities that are sold at galleries and consumed by a few individuals. As for writers, they are interacting with a larger public, due to the availability of their creations on a minimum price.

With the publication of Maghrib mein Funn-e-Mussawari ki Tehreekin, one hopes that it will fill many gaps as the book is not for students of art alone; it can be accessed by general readers. Due to its language it communicates complex themes in a clear tone. For instance, translating European names and terms in Urdu is a recurrent problem for many writers. But the authors in their introduction state their strategy -- not only have they transliterated English terms, these are also written phonetically so that they can be pronounced correctly.

Another appropriate characteristic of the book is that the authors have refrained from ‘translating’ existing terms of Western art. These are written in the Urdu script, instead of converting them into Urdu language, which could have caused a series of confusion and complexities. The authors’ decision to adapt English names in Urdu script as well as in Roman letters indicates the way our world is not pure or puritan, but a blend of many strands. Their simple and sensible approach also reminds of an anecdote narrated by Ajmal Kamal, one of the most significant translators in Urdu. While working on a text, he consulted the official dictionary of Urdu terms and found out that the Urdu substitute for computer is Mohsib (an Arabic word). He then looked in the Arabic dictionary to discover that the translation for Computer is Combuter. A case of common sense, indeed!