Who would teach her how to get over the terror of springtime? She needed meditation

The light hurt her eyes. It was spring and she already missed her days of living in the well looking up at the silver sun, cold as a mirror.

The burgeoning had begun. Life breaking through the earth, through the bark, breaking through its own skin into sheaves of fresh colour. It seemed like the carnival was about to begin which made her slightly giddy, unsteady on her legs, shrill in tone of voice. How would she get through it? Perhaps breathing in deeply from the pit of her stomach and breathing out evenly would help create a wave, a hissing wave that would inhabit her stillness.

Maybe she could slow down, slow down, to catch up with the carnival, her heart did not feel ready. What had he been taught in that story, Arjun in the Krishna story, about how to participate in what you had no feeling for? She could not remember how that turned out but she knew how to stand shock still and stable and remote like a mountain, fixing her eyes like she was looking into the eyes of an animal.

Except that animals, birds, even fish held human beings in such contempt they seldom consented to look them in the eyes. Not even caged animals would do that; the lion at the zoo grazed past your ears into a glazed distance, the bears in the paddock pretended to have developed a squint, the giraffe became all coy and virginal with a dupatta of green leaves between his teeth and the intelligent elephant looked like he needed eyeglasses.

Only the monkeys, those close relatives, peered at you from the other end of their enclave, baring their teeth as if laughing at you, then screeching and hurling imprecations in your face. How could she learn to look beyond the cage of her mind? How could she stop her mind from twirling, whirling, twisting around the sharp edges of words to drop the robes and walk out naked and unashamed like an animal?

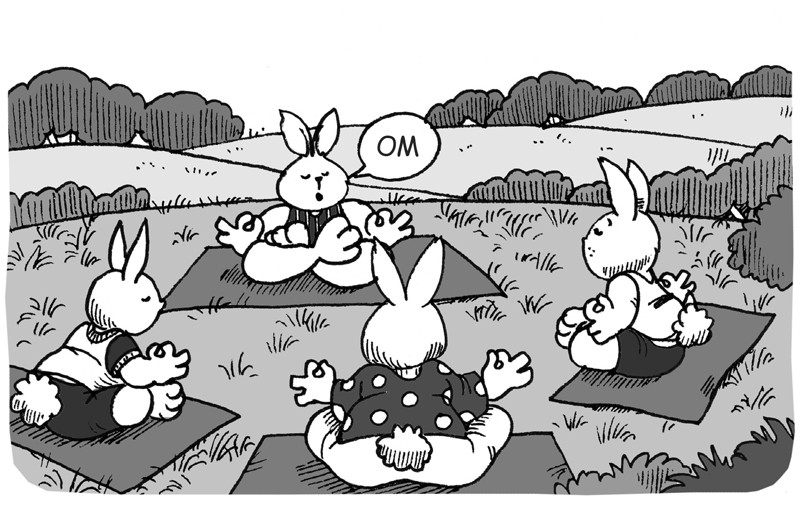

The spring was insistent. The time of the toads had arrived and she was pressed to step out of her well and mate like every sentient being around her was mating. Sure, tadpoles were cute in their miniaturised glumness but she had no desire to replicate herself in anyone, condemn them to live off swallowing quantities of mosquitoes and gnats. The universe could barely look out for itself and she was not about to burden it with her brood. There must be some species that did not care to replicate itself but was just fine with mortality. Who would teach her how to get over the terror of springtime? She needed meditation.

The first yoga teacher she found was a single mother, devoted, devout, so she could not bring up the issue of the tadpoles with her. But she did react to the other students there, the cool, blue people who disembarked from darkened limousines in designer casuals and imported shades, their body guards carrying the yoga mat, soft slippers, towel and bottle of mineral water. Her teacher told her not to be judgmental.

‘We are what we despise the most in other people,’ she said, which was a way of telling her she was as narcissistic as any of them, without the barrels of money.

‘This is not the age of celibate monks,’ her teacher told her, ‘who retire to the forests to meditate on a vow of poverty.’ The teacher asked her to forgive herself for being such a fraud. To her confused mind, the two mantras seemingly cancelled themselves out. Was forgiveness not part of judgment?

‘Besides,’ her teacher argued, ‘if the powerful of the world -- or at least their overweight wives -- change their ways a little is that not beneficial to Universal Spirit?’

She learnt how to stand poised like a tree in class, vulnerable and quivering, with her mind not quite at rest. Meanwhile, she kept the other students locked in the corner of her eyes, like the animals at the zoo had taught her. Her species didn’t have that much going for it, she felt.

But the rules kept changing all the time, from the days, the timings, number of sessions, to the cost of each session that kept going up. When the teacher refused to turn up or cancelled out or sent in an advanced student in her place, she said it was to teach students how not to anticipate anything and to be prepared for all contingencies.

It was when she declared: ‘Dependency is not love,’ that it was time to look for another teacher.

Her second yoga teacher informed everyone in the introductory class that although all instruction was in English, her class would have a strong Arabic flavour to it, not vernacular Arabic, of course.

‘Words like "Om" will be changed to "Allahu", keeping in mind the proclivities of the participants,’ she announced. ‘There will be namaz break during class, two of them, if necessary.’

She said her sheikh had instructed her for this to be the way and anyone in class could consult him for a personalized vird but since he lived abroad this could be done online in dollars. Virtual religion dispensed in dollars was not her kind of thing so she kept on walking.

The third yoga instructor was an ageing classical dancer whose emphases were always on form, the geometry of grace, moving like you heard dhrupad in your head. She prohibited conversation of any length concerning ideas.

‘Art is not about ideas,’ she said, ‘but about doing something patiently, passionately, every day. And if it comes hard to you that is because your love is flailing’, she declared. ‘Ideas kill life,’ she said, ‘kill the moment’.

She tried to explicate the cosmic dance of Shiva that destroyed and created, always needing its opposite, and when you said you didn’t get it, she said:

‘Ignorance too is necessary because it moves inquiry along’.

But she was good, her teacher, and taught her that understanding was not all there was to it because, maybe, life was not a problem.

Meanwhile, spring was gaining ground and the shameless, sensual flowers would soon be out like female ramp models peddling their wares, pausing to be caught in a wooden pose. Flowers had no restraint, waited to be admired, luring all manner of clients to their lair of nectar. Flowers had no testosterone and were far too, well, florid. Maybe she should look for a hirsute male teacher, gangly and gravid, more at peace with his body.

The first male teacher she met was young, thin and pale. He had just returned from California and was into his father’s business. He asked her to try the headstand on the first day in class.

‘This is to confront the fear of the body’s fragility,‘ he said.

He gave her a number of scientific reasons for it too but she thought it was a great way to change perspective. He demonstrated it with a flock of other male students standing on their heads, a slow moving dhammal in the air, upended, complete with pirouettes and splits that made an offering of sex organs till the legs went over the head and touched ground. He was good, good and taught her how to laugh at her fervidity.

But then the studio started giving in to New Agey ideas and music was introduced of the wallpaper variety. Her teacher started talking about how hot yoga worked wonders and the trance dance that he would soon teach them. His aunt was opening up a chocolate place, so all students were asked to check it out for the Kundalini-cacao experience that was great to lose weight, age, worries.

‘Chocolate is an anti oxidant, anti depressant, an aphrodisiac,’ he advertised. So there you were, back to the obsession with the body beautiful. She would have to leave before hot chocolate yoga came to class.

That is how she met her last guruji who understood her well. He insisted on being addressed by the title because he was older, an organic farm owner who lived outside town and wore homespun cotton kurtas with his hair like a shaman in a ponytail. He listened to her explain how oppressed she felt by the florescence, the demand for a certain exuberance called sap.

He taught her to lie flat on the ground facing upwards, shoulders expanded and into the floor, arms to her side, palms upwards, her feet joined at the heels but the toes falling to the sides. He taught her how to unclench her mind and to smooth out her skin of her eyeballs, the back of her tongue, and the labyrinth of her ears. He taught her to surrender to the earth in full faith that she would be held, with the dreams coming in tears. He taught her how to escape her species to become vegetal, tuber.

She felt herself falling inwards, back into the well, hoping this time whatever little she had to offer would be enough.

Don’t miss Samina Choonara’s other short stories, The burgundy cardigan and The white pigeon, written exclusively for TNS.