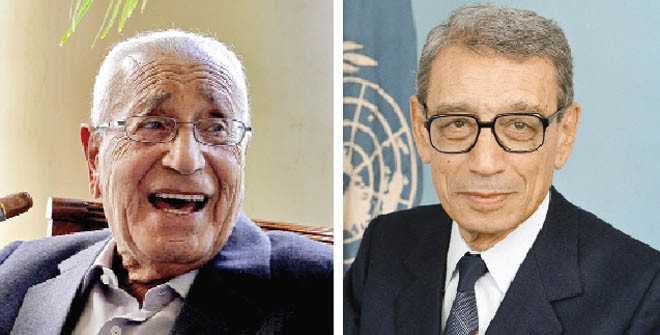

Boutros-Ghali and Hassanein Heikal followed different paths but one was much greater than the other and Heikal was his name

For keen observers of the Middle Eastern politics, the deaths of Boutros-Ghali and Hassanein Heikal on Feb 16 and 17 respectively have closed two important chapters. They were of almost the same age, 92 and 93, and their influence spanned over most of the second half of 20th century. Though they belonged to very different families, their trajectories helped shape the politics of modern Egypt in their own way.

Politics was not new to Boutros-Ghali since his grandfather Boutros Ghali Pasha had been prime minister of Egypt from 1908 until he was assassinated in 1910. He was the first Coptic-Christian to receive the title of Pasha from the Ottomans. After his assassination, the family decided to honour him by changing the family name from Ghali to Boutros-Ghali hence the double Boutros in the name of Boutros Boutros-Ghali.

Heikal was educated in the American University of Cairo and Boutros-Ghali graduated from Cairo University in 1946 and moved on to complete his PhD in international law from the University of Paris in 1949. While Boutros-Ghali was pursuing his academic career, Heikal had his first mission as a reporter in the Second Battle of El Alamein when he was hardly 20. Their early lives in the 1940s, to a great extent determined their future course of action -- Heikal becoming a renowned and arguably the greatest journalist of the Arab world and Boutros-Ghali transforming into a world-class diplomat ultimately heading the largest organisation of countries on the globe.

After World War II, Heikal often cut across the borders between journalism and politics. He developed a close friendship with Gamal Abdel Nasser who was spearheading a revolution of sorts in the 1950s’ Egypt.

Post-World War II period was very interesting in the Middle East; leftist politics was clashing with the old regimes in various shapes and sizes. Egypt too was a boiling pot of opposing ideologies and a battle ground for political activists. In all this tumult Boutros-Ghali preferred to remain a laid back professor of international relations and law at Cairo University for almost 30 years till the mid-1970s.

These 30 years Heikal spent in a whirlpool of journalism and politics, rubbing shoulders with some of the greatest leaders of that era. Heikal’s partnership with President Nasser of Egypt was ushered in a new era for this country of the Nile and was influencing the entire Arab region. Nasser and his fellow army officers had toppled the kingdom of Shah Farouk and were looking for a new narrative and that discourse had to come from Heikal.

Heikal not only helped Nasser write his landmark speeches but also a political manifesto, ‘The Philosophy of the Revolution.’

Under Nasser’s patronage, Heikal became the editor-in-chief of newspaper Al Ahram -- a newspaper launched by the Lebanese Takla brothers in the Egyptian city of Alexandria but later moved to Cairo and nationalised by Nasser. Heikal’s media excellence helped Nasser remain the most popular Arab leader in the 1950s and 60s. As editor of Al Ahram for over 15 years, Heikal transformed the journalistic landscape of Egypt in consonance with Nasser’s ideas. Both strongly believed in pan-Arabism -- an ideology that flourished after the First World War that saw the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. But pan-Arabism had its heyday in the 1950s and 60s and declined after the Arab-Israel war of 1967 that ended in an ignominious defeat for the Arabs.

Heikal’s weekly column ‘Frankly Speaking’ was one of the most widely read pieces of journalistic writing in the Arab region. He remained a public voice of Nasserite secular Arab nationalism even after Nasser’s sudden death in 1970. From the nationalisation of the Suez Canal and the shift to a socialist camp to getting involved in campaigns against the US, Israel, and the Muslim Brotherhood, Heikal and his paper endorsed Nasser’s legitimacy and encouraged him to embark on large-scale battles.

The first major setback that Heikal faced was the aftermath of the 1967 defeat. He had been rephrasing facts, such as calling the defeat against Israel a ‘relapse’, and withdrawal a ‘reconciliation’. But his journalistic expertise could not pacify students who had started protesting against Nasser in Cairo University -- where Boutros-Ghali was a professor, not involved in active politics but closely observing the unfolding events.

The events of 1970s saw Heikal gradually moving away from the corridors of power and witnessed Boutros-Ghali slowly stepping in. Though they did not cross each other’s paths, it was evident that an era of old revolutionary politics advocating pan-Arabism and socialism was coming to an end.

The rightest politics of Anwar El Sadat and Boutros-Ghali was emerging from the ashes of Nasserite and Heikalian leftism. The rhetoric that had lost its sheen and Arab territories had given way to negotiations at Camp David to regain the lost Sinai Peninsula. The singular achievement of the late 70s diplomacy by Boutros-Ghali and Anwar El Sadat was isolation of Egypt from its Arab brethren resulting in the assassination of Sadat by extremist groups opposing relations with Israel.

Boutros-Ghali served as Egypt’s minister of state for foreign affairs from 1977 until early 1991. Throughout the 1980s, when Egypt was almost ostracised by revolutionary Arab governments such as Libya and Syria, Boutros-Ghali managed excellent relations with General Zia’s Pakistan that was fighting a so-called American sponsored crusade against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. The supply of Stinger missiles to the guerillas is well documented in Charlie Wilson’s War that was also made into a movie in 2007 starring Tom Hanks and Julia Roberts.

Perhaps recognising Boutros-Ghali’s services for almost fifteen years, the western powers supported him in becoming the head of the United Nations in 1992. He was the first African, the first Arab, and the first Coptic Christian to be elected to this exalted office. His five-year term was marred by the failure of UN efforts in Somalia, Yugoslavia, and Rwanda resulting in large-scale civil wars, massacres, and disintegration of countries.

Though he later blamed his failures on American treachery and the world’s inability to offer him the required resources, he remained as ineffectual in world affairs as he was in achieving peace in the Middle East.

Boutros-Ghali’s tussle with Americans prompted the US to veto his reelection for the second term and he was replaced by Kofi Annan, another African diplomat. When Boutros-Ghali was proving himself a failure at the international stage in the 1990s, Heikal was continuing with his journalistic pursuits without joining a single publication. He continued writing for different newspapers and magazines and producing books on the history of his times. The multitude of thriving journalists that he trained and guided goes into hundreds, if not thousands.

In the final analysis, the two great men of Egypt followed different paths but one was much greater than the other and Heikal was his name.