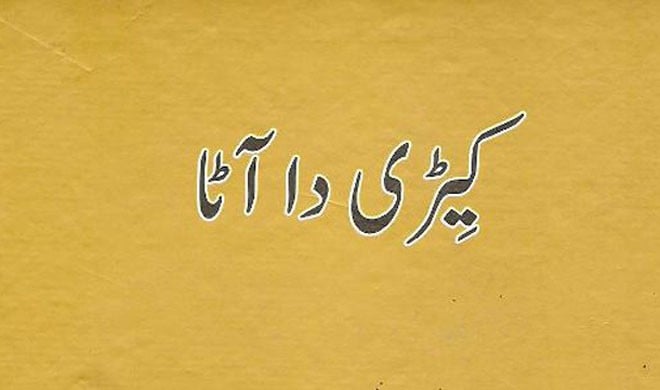

Ayub Awan made a conscious decision to write in his mother tongue and KeeDi da Aata was his first collection of Punjabi verse

Another Mother Language day and another disappointment for language right activists. Another year of activism has ended and Punjab is still without its own language. Lingual apartheid is fully on with the open consent of Punjabi bureaucracy and politicians. They are determined not to allow even a single Punjabi line in Punjab Text Book Board’s curriculums prepared for public primary schools.

Language, art, culture and heritage are officially being buried under concrete loads of orange and yellow lines. However, until hope and history rhymes, every new Punjabi poem and a fresh prose line will remain not only an act of intellectual resistance but celebration of our thousand year’s old written literary tradition and history.

One of the lesser known historic regions of the Punjab is Soon Sakesar (Distt. Khushab). It’s a 35 mile long valley comprising of 32 villages that extends from my ancestral village of Padhrar to Sakesar, the highest peak in the Salt Range. During the colonial period, it administratively belonged to the Shahpur District represented then by British favourites Umar Hayat Tiwana and his son, the last premier of undivided Punjab, Khizar Hayat Tiwana. Before partition it had an equal mix of Hindu, Sikh and Muslim Punjabis. One of the ancient three storey Hindu temple in village Amb is considered to be built around 9th Century AD.

Grierson’s all inclusive Lahndi (Western Punjabi) has many dialectic branches and the one spoken in Soon Valley and tehsil Talagang has been named as "Awan Kaari". KaRana Bar on the one side and Dhan-Pothohar on the other with Shahpuri and Thalochi-Saraiki neighbourhoods, Soon Sakesar has a unique lingual and cultural significance for the students of Punjabi language and heritage. Nevertheless, it broadly remains unexplored and neglected apart from the hawkish eyes of army recruiters.

Shaheen Malik’s two volume area and cultural study titled as Awan Kaari (August; 1987) and Lehndi She’r Reet (October; 1987) remain the most extensive works in Punjabi about Soon Valley. Imtiaz Hussain Imtiaz’s Zilla Khushab also carries significant cultural details of the area. These three books are published by Pakistan Punjabi Adabi Board, Lahore and are currently out of print. Ahmad Ghazali’s Soon Sakesar and Sarwar Awan’s Wadi-e-Soon Sakesar are available for Urdu readers.

In English, Hardev Bahri’s Lahndi phonology: With special reference to Awankaari (Bharati Press; 1962) is an important read. Hardev’s mother belonged to village Khabeki. Irony of the Soon valley is that its two most famous literary icons, English novelist and Journalist Khushwant Singh (born in Hadali) and Urdu poet and fiction writer Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi (born in Anga) never preferred writing in Punjabi.

Ayub Awan rejected that populist lingual choice. He made a conscious decision to write in his mother tongue and KeeDi da Aata (reprinted in 2011) is his first collection of Punjabi verse. He is a consultant psychiatrist by profession and is currently based in Kingston, Ontario (Canada). He was born and raised in village DhadhaR. He received his college education from Lahore and Multan. Poet and activist Abid Ameeq inspired him to write poetry in Punjabi when he was a student at Nishtar Medical College, Multan. Most of us who left our ‘wattan’ (our birthplaces) for higher education and other reasons did get influenced by the more prevalent dialects of big cities but Ayub’s astounding achievement is that his diction and dialect remains so originally local and native. KeeDi da Aata when first published in 1994 was then the only modern Punjabi poetic print in Awankaari dialect.

There are forty seven poems in this collection and most of them are socio-political in nature. Ayub was actively involved in the left politics of 1980s. Those optimistic and rebellious days seamlessly appear in his poems. His poetic voice is softer and sadder but in later poems, when bitterness and disillusionment enters, his voice becomes considerably loud. Lines like these sum up not only that entire era but narrates contamination of the political resistance too: Paal baNao/ Hik doojay day aggay pichay/ vaar-o-vaari aao/ jehDa daana hath wich aanay/ Apnay kheesay pao/ pichay muD kay kaddi nah vaikho/ Apni khall bachao/ LaiN ich aao. Another such poem is JannatiaaN da gawan: Saadi dhoN tay apnay payr/ JinhaaN nay nit dharray / SaadiaaN manggaaN pallay paa kay, jehDay khãray aap chaDhay/ Aao ohna da gawan gã’eay. His grievous tribute to Shaheed Nazeer Abbasi who was tortured and killed by Martial Law authorities in August 1980 is a lament of its own kind that is composed as a lyric:

Another aspect of his poetry is his reaction towards wars. His anti-war poetry is such a rewarding reading experience. Anyone born in the salt range is not alien to the world of army recruitment and the phony colonial concept of martial races. However, Ayub’s response to the war mongering is so humane and universal. His father was part of Pakistan army serving in (then) East Pakistan in 1971 where he was taken as a Prisoner of War (PoW) by Indian army. Soon Sakesar was emotionally and psychologically shaken by that conflict. There was hardly any home that didn’t felt the pain of that war as every village on average has sixty to seventy PoWs at one time. Due to strong sense of community and blood relationships in the valley, it became a collective sense of suffering, trauma and agony. His poem اسیں ڈھیریاں بال کھِڈندڈےis epitome of that grief:

There were calls of war again/ and our dads went to fight oversees / we were left playing in the dust, abandoned/ No one came to console us.

There are few romantic poems too in this collection and hunn milso taañ keeviñ hoso, Hath jinhaañ nay and Maal Road tay turna are worth reading. He is a poet of considerable talent but he didn’t take poetry that seriously. He remained disillusioned and unconcerned for a long period of time taking this saintly act of creative writing too casually. He explains that in the title poem of his book:

Ayub Awan belongs to the last generation of Soon Sakesar who has truly lived through the rooted and organic cultural value system of the valley. He is one of those few who are capable of creating an artistic fusion of modernity and tradition rhymed around our rugged land. If he fails to prioritise poetry then there isn’t anyone else who can compose our alpine lyric. His unpublished poems like تلے گنگ دیاں بھیڈاں, بابے طورے دا درس and چِڑی دا دیس strongly suggest that he has much more to offer in Punjabi, perhaps more than what he, himself believes in.