A mesh of tales and myths, incongruous and discordant but eloquent nonetheless

In the labyrinthine womb of Delhi -- some liken it to a belly -- are nested immortal legends and myths, resurrected time and again by story-tellers, yogis, messiahs, poets, vendors and not to forget travel guides. Delhi, built over thousands of years, one shehr (also pronounced as sehr) added to another, to pander to the imperial fancies, is custodian of bewitching tombs, shrines, temples and monuments.

On a recent visit to Delhi monuments, I encountered a mesh of tales and myths, many incongruous and discordant if tested on the touchstone of historical facts. But if the coin of historiography is flipped, these come across as a wondrous art of story-telling that has enthralled man since his birth.

Just as jagged rocks overlooking the sprawling seashore, blend into horizon if viewed from a distance, the seemingly bizarre myths are seamlessly woven into an ancient tapestry by an eloquent guide. I am witness to this plastic transformation.

At Qutb Minar, with the imposing tower framed by the branches of the old tree, and a squirrel jumping up and down the gnarled, knotty branches of a neem tree, the guide began narrating the story of construction of the Minar:

"A millennium back, close to the fabled Indraprastha, the capital of Pandva brothers, where Yudhishthira had set up his magnificent court, and built Mayasabha, a grand assembly radiating illusions, another powerful king Prithviraj Chauhan commissioned the building of a minaret for his daughter, with its balcony opening on the north, so that she can have darshan -- a visualisation of a manifested deity -- of Yamna nadi, shimmering in the golden sunlight and silvery moonlight, oblivious to its grandeur and its spiritual hold over the denizens of the city.

"But as ordinary men and women are not immune to vagaries of destiny, likewise, Prithviraj Chauhan was defeated by Mohammad Ghauri, who after handing over the control of conquered territories to his slave general, Qutub-ud-din Aibak, went back to Ghazni. To set up a landmark of victory, Aibak began constructing the second storey of the minaret. Not only the fortunes of Chauhan dynasty swapped on the shafts of time, the cylindrical bars of the minaret also rotated on the axis and changed directions. The northern balcony with a view of ghats of Yamna was shifted to paschim (west) -- in the direction of Makkah."

"Is it called Qutb Minar after Qutub-ud-din Aibak?" I asked the guide.

"Perhaps yes. Perhaps not. It could be named in honour of Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki, a sufi saint, buried close to Qutb complex."

In a short while, the guide metamorphosed into Scheherazade of Arabian Nights, opening one story into another, like the interior arches of Mughal mosques.

And as the myths drifted in and out of each other, the minaret manifested its polyphonic existence through embellished calligraphy, which was interlaced with blooming padma -- the sacred lotus.

As we were strolling around Hindu/Jain temple remains -- the guide pointed out that some of the deities, carved out onto the temple pillars, were defaced such as Saraswati, Ganesh and Hanuman -- lofty red sandstone and white marble arches, wells and tombs, the guide narrated story of Iltutmish’s tomb: "his physical remains were buried deep into the earth and a facsimile tomb was raised on the top. Even after death, king was not safe from revenge depredations of his enemies."

And pointing to a circular, incomplete tower-like structure, the guide recounted: "It is Alai tower. Ala-uddin Khilji was determined to build a minaret taller than Qutb Minar, which would stand testimony to his military success in India, but before the first storey was completed he passed away."

Not only is Qutb complex filled with architectural gems, it is also a living tapestry of tales of conquest, revenge and vanity, all gathered together like colours of a rainbow.

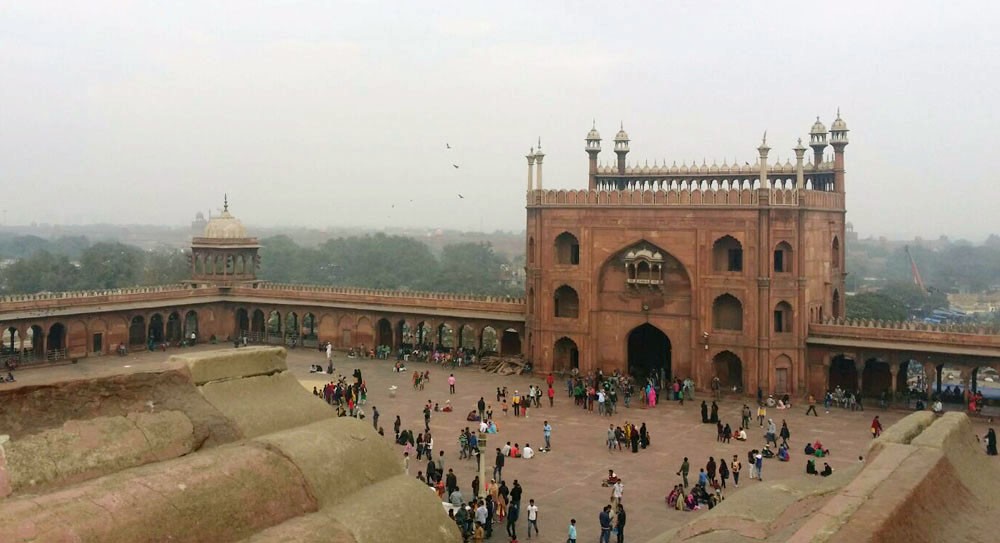

In Delhi, emperor Shahjehan built an eponymous shehr, with its famed attractions of Red Fort, Jama Masjid and Chandni Chowk. As Red Fort was closed for tourists after the Republic Day festivities, I reached Jama Masjid and decided to explore the breathtaking mosque - its domes, chhatris, cusped arches, and minarets, and three imposing entrances by unravelling the known myths.

The most famous story associated with Jama Masjid is that of a naked mendicant, Sarmad, who was close to Dara Shikoh (favourite son of Shahjehan) and who was also murshid of Hazrat Mian Mir, buried in Lahore. Sarmad, the naked faqir was beheaded on the steps of Jama Masjid and, according to folklore, after his decapitation, he began climbing the stairs holding the bloody head in his hands, till the voice of his pir Hare Bhare Shah boomed and beckoned him to step down the stairs and take his ‘veiled sleep’ in a grave next to his own. This story of Raqs-e-bismil, dance of the wounded, which frequently recurs in the sufic-lore echoes that of Mansur al-Hallaj, who was beheaded in Baghdad for his repetitive ecstatic strain of Ana ‘l aqq ( I am the Truth) and whose body also trembled with joy after the gory killing.

And another myth yoked with the Jama Masjid is that a minbar-pulpit was raised above the peacock throne, the imperial seat of Mughal emperors, which was later carried away as war booty by Nadir Shah Irani, who vandalised the city and massacred its 100,000 inhabitants.

An intriguing question can be raised: Can spiritual power ever need to be equated with temporal power? As wanes political power, spiritual clout allied to it also slips down the ladder. Jama Masjid, occupied by British forces after the war of independence, was spared destruction on the prodding of some of its officers like Henry Lawrence, governor of Lahore. And even now the algae-encrusted water pond of Jama Masjid whispers echoes of its dwindled fortunes.

And as I was ending the visit to Jama Masjid and looking at Red Fort from the Eastern gate, two small minarets attracted my attention. I asked an old, bespectacled, ticket-checker outside the tower, who had earlier laughed at my dishevelled state after I climbed down the tower’s winding stairs. He replied that it was the shrine of Sufi Sarmad. Suddenly, the myth lost temporal inertia and attained spatial dimensions.

I stepped down the 35 stairs of Eastern gate and entered two adjacent shrines: one red, another green. The green shrine is that of Hare Bhare Shah, akin to Hazrat Khizar, a living saint, who is found where two oceans meet. And red shrine is of Sufi Sarmad, signifying his martyrdom. Perhaps the green and red stand for two oceans; both flow into and out of each other.

Not only the shrine of Sarmad faqir brought joy to the heart, I was also amazed by the traversing of myths in space and time. The builder of Qutb Minar is buried in Lahore, and a mendicant, beheaded on the steps of Jama Masjid, sang and danced in the streets of Lahore.

Perhaps myths and legends do not pass into oblivion. We do.