One of the great lessons to be learnt from Intizar Husain is the freedom to imagine and the independence to read as one would like to

It is not possible for me to write an obituary for Intizar Husain. I cannot get myself to speak of him in the past tense. For me, he is and will remain a man of the present. Many people associate him with a nostalgic yearning for the past. However, I recall that once he remarked that he lives in his own time which has elements of the past as well as the present.

This makes me think of William Faulkner who said that the past is not dead, it is not even past. When I look back at the time since I first started reading Intizar Husain, initially with bewilderment but later on sensing the tragic beauty and deep, beguiling and haunting half lyricism, I can only say that he has enriched my life as no other writer. Such writers do not die and he, too, has joined the Assembly of the Immortals where he truly belongs. Intizar Husain, the man, is no more but Long Live Intizar Husain, the writer!

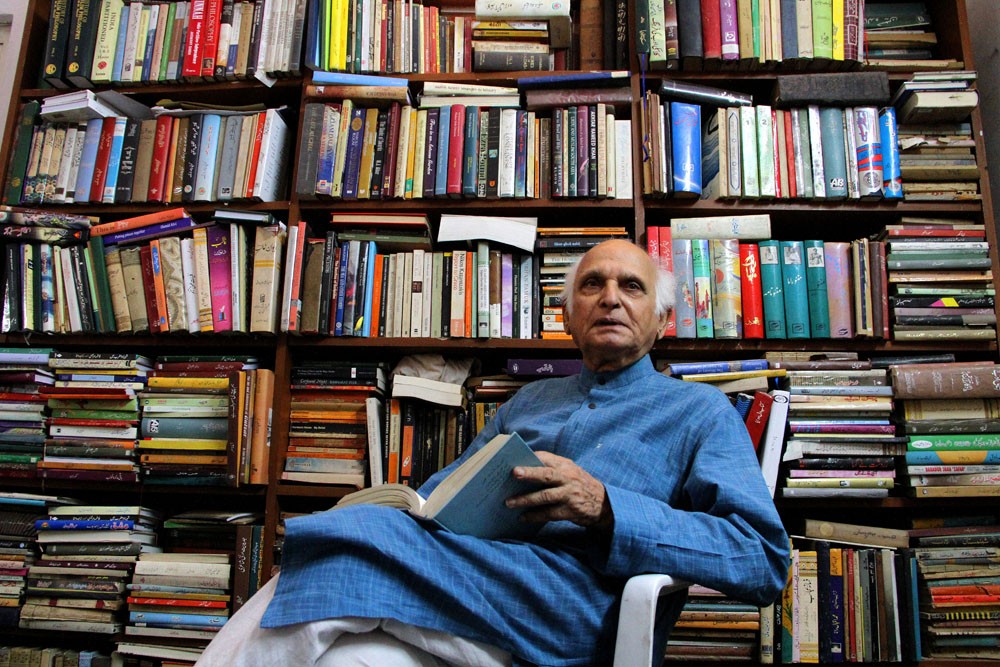

For the last three years I was engaged in writing a book-length study of his work and was in almost daily contact with him. As I pestered him with a seemingly endless barrage of questions, he would put up with me in his engaging style, more amused than annoyed. This did not stop him from chiding me for my constant distractions and one fine day, he categorically told me that he would like to see the book in his lifetime.

When I dispatched the bulky packet to him, he rang me up a few days later to inform me with characteristic aplomb that there were errors of proofing in it and that he has corrected them. No mention of the errors in judgment or mistaken assumptions. He would never force his opinion on others. He would let everybody draw their own conclusions, not bothering much with what critics and reviewers had to say. He carried on his work in his own inimitable style.

His memories I will cherish all my life but I would rather not dwell on these for the time being. These memories are still in the realm of the personal. I would rather speak of the legacy of the work which will continue to survive.

Intizar Husain’s work is in diverse forms and now looking back at the accumulated richness, I am equally surprised with the variety as well as the remarkable ease with which he makes each form convey his inner vision. He is best known for his short stories and there he is peerless.

From the realist he moved towards the symbolic mode, exploring a variety of moods and styles. It is easy to see that he is astride the two divergent types or kinds of storytelling, moving from the Chekhovian to the Kafkaesque, yet he is so strongly rooted in his own tradition that he remains truly himself.

Not a mere extension of short stories or forcibly elongated versions, his novels deserve to be explored in detail. My own favourite among his writings is the novella Din which was published together with Din Aur Dastaan to make up a volume. However, it was the novel Basti that came to be his best known book both at home and abroad. Superbly rendered into English by Frances Pritchett, it has been reprinted by the New York Review of Books to reach a larger international audience.

While it is complete in itself, I see Basti as the gateway to a trilogy which explores Pakistan’s descent into a land of despair and disillusionment from the Promised Land it had set out to be. Characters move across historical time but somehow their predicaments remain the same. They make an attempt to move across borderlands and make some connection with the past they have left behind in another land but they fail miserably and this makes them lose their grip on the present. "I write about tormented times," Intizar sahib would use the Urdu-Persian word ashob to describe his creative impulse.

Read also: Taking us to a world that was unfamiliar and unexplainable

A unique aspect of his creative work is its connection with the critical essays he wrote. Taken together, these essays have an astonishing range, covering almost the entire Urdu canon in which he comments on almost every major writer. His concerns as a short story writer come up and he takes issues with the kinds of writings which are outside his realm of interest. He took up arms in his earlier phase with the work of Krishan Chander and his colleagues were producing but his stance softened later on.

For him, literature was an integral part of the cultural experience and this is the point of view from which he wrote. His openness to the dastaans as well as ghazal poetry make him one of this rare critics who make you want to read and explore the works of literature rather than chase ideological shadows. No wonder that Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, himself the doyen of Urdu letters, regards Intizar Husain as the foremost critic of the present day.

It comes as a surprise to some that I regard his plays as an important aspect of his creative work, an important dimension by themselves. But this is primarily because his plays were not easily accessible and they have just been published, although the plays had been staged earlier. His full-length play, Khwabon Kay Musafir, is as characteristic a book of his as the better known Basti. In his plays he explores some areas of experience which are akin to, but different from, his fiction. This play has been staged a number of times with great success. No less a person than Zia Mohyeddin praised the great sense of stagecraft which makes these plays unusual in contemporary Urdu literature.

His journalistic pieces do not represent the dark side of his creative persona. Rather, I see the volumes of his collected columns as a richly detailed chronicle of the cultural changes which took place in Pakistan’s society over the years. His memoirs and remembrances in Chiraghon Ka Dhuan constitute a vivid and nuanced portrait of the dynamic city of Lahore. The autobiographical Justujoo Kiya Hai unfolds like a novel and seems to me to be a remarkable example of his capability to develop experiences and impressions into narratives.

His depiction of Hakim Ajmal Khan and the biography of Delhi as a city are less of biographies in the strict sense of the term. Capitalising on the imaginative freedom with which Intizar Husain had rechristened Ghalib’s letters and Azad’s Aab e Hayat as "novels", I would like to read these books as nothing but novels. After all, one of the great lessons to be learnt from Intizar Husain is the freedom to imagine and the independence to read as one would like to.