Two passionate and prolific little-known historians, Maulana Muhammad Ishaq Bhatti and Hussain Arif Naqwi, passed away recently

Maulana Muhammad Ishaq Bhatti breathed his last in December 2015. He was 91. With his death, Pakistan has lost one of its prolific historians. The news would have been ignored by readers (especially of the English press), having never heard his name. Even those familiar with him would fail to recognise him as a ‘historian’, let alone a prominent one.

The reason for this insouciance towards that unsung scholar is not just sheer lack of appreciation for scholarly work in Pakistan, but also a narrow understanding of the discipline of history. In Pakistan, history has been reduced to a summation of facts dealing with the establishment of Pakistan. Such political history in its most reductive form has left little scope for appreciation of work done by other historians.

It only requires appreciating that history is not simply a recounting of events relating to the Muslim League, Iqbal, Jinnah, two-nation theory and Pakistan movement. Nor is postcolonial theory the only frame of inquiry for writing of history. There can be various modes of approaching the past and writing about it. What is classified with a rather negative connotation as ‘hagiographical’ account of the lives of religious scholars is one of them. It offers a wholly different way of exploring an important part of the history of this region and helps us understand its various convolutions.

Maulana Muhammad Ishaq Bhatti was one such historian. Born in Faridkot, Ishaq Bhatti lived an eventful life. In his youth, Bhatti campaigned for political rights in the princely state of Faridkot with a local, Congress-affiliated group. During his years of political activism, he made friends with the likes of Zail Singh who went on to become India’s president during the 1980s. He even got jailed during the Raj.

Prison exposed him to a sense of comradeship. While in jail, noted Bhatti in his autobiography, an old Sikh prison mate would often wake up young Isaak Mammda (Muhammad Ishaq) for fajr prayers. Bhatti never forgot the lesson of inter-faith harmony and adhered to it throughout his life, as expressed in his ideas and writings too.

Despite being a devout Ahl-i-Hadith, Ishaq Bhatti was friendly with the religious scholars and leaders of every other religious denomination. In the huge corpus of scholarly work that he churned out in his long life, the prolific Bhatti pushed his pen about major religious figures of Deobandi, Barelvi and Shiite Muslims and their contributions to the Islamic tradition.

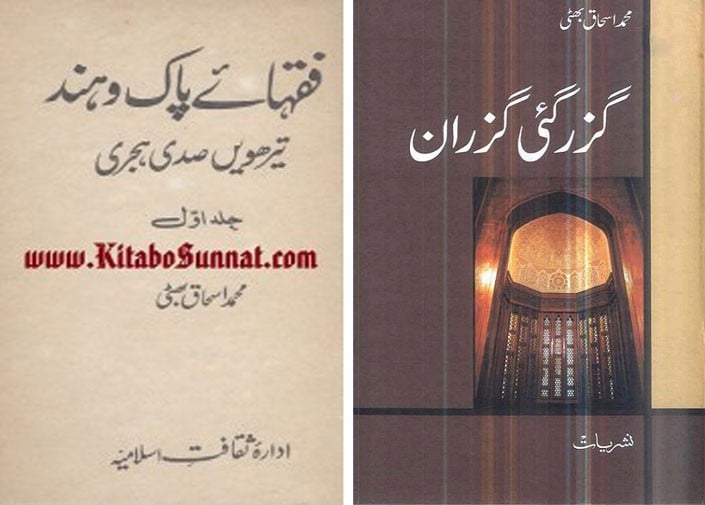

Ishaq Bhatti had an interesting career. He worked for an Ahl-i-Hadith newspaper, Al-A’itasam, when he moved to Lahore after partition. When the Institute of Islamic Culture was established in the 1950s, he got appointed there as a research fellow. His stint at the Institute of Islamic Culture was immensely productive as Bhatti published an impressive amount of scholarly work. His magnum opus was the multivolume history of Muslim scholars in India and their contribution to Islamic fiqh. Another significant work was an annotated Urdu edition of Ibn Nadeem’s Al-Fehrist.

After his retirement from the Institute, Bhatti got interested in writing about the Islamic movements in South Asia dating back to the colonial period. He wrote biographies of mostly Ahl-i-Hadith scholars and their scholarly contributions. In this way, he has left for us a wealth of information about the recent history of Islamic religious literature produced in South Asia and the inner world of the scholars who produced it.

The prime locus of Ahl-i-Hadith movement was Punjab. The work undertaken by Bhatti helps us understand the processes which have been taking place since the late nineteenth century whereby changes in social environment, political exigencies and economic conditions brought about varied religious responses in both the rural areas and the urban centres. As a religiously devout man, Bhatti was concerned with chronicling the details of those who had served the cause of religious persuasion that he thought was the most authentic. By doing so, he has left an intellectual legacy which is indeed invaluable for the succeeding generation of social historians.

Another historian who passed away recently is Husain Arif Naqwi. Just like Ishaq Bhatti, I rank him to be one of Pakistan’s important historians whose death went unnoticed. Naqwi was a school teacher, committed to the worthy cause of collecting information about various Shia ulema, their biographical details and scholarly contributions. His tazkira or biography of various Shia ulema is the best work available on this topic.

Not affiliated with any university or getting funded by local or foreign scholarships for research, Naqwi used his own resources for travelling the length and breadth of Pakistan for research purposes. He would usually spend the summer break in different libraries across Pakistan collecting research material. Like Bhatti, Naqwi was also open towards the followers of different religious persuasions and was friends with various Deobandi, Barelwi and Ahl-i-Hadith scholars.

I have had the good fortune of benefiting from the scholarship of both Maulana Ishaq Bhatti and Husain Arif Naqwi. In fact, I am not the only one; they both helped scores of other researchers interested in the history of modern South Asian Islam. Martin Riexinger, now a professor at Aarhus University in Denmark, wrote a comprehensive book on the history of Ahl-i-Hadith movement in South Asia. He made extensive use of Bhatti’s works on Ahl-i-Hadith ulema. Andreas Rieck’s book The Shias of Pakistan on the history of Shias here has just come out, and is based extensively on the research material generously shared by Naqwi.

The works of Bhatti and Naqwi will continue to guide and inspire numerous other scholars in the coming decades. It is, hence, important to recognise the scholarly legacy and services of such passionate and prolific scholars.