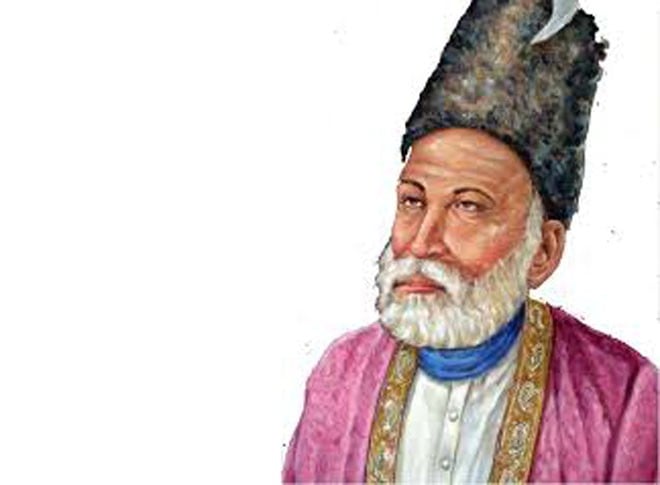

A poet of the highest stature, Ghalib’s prose too is simply exquisite. His letters are witty, stylish and elegant. His vocabulary is dazzling. The perfect ease with which he chooses to use an Arabic, sometimes a Persian and, more often than not, a proper Urdu word for one and the same object, reflects the integration of his personality within a highly composite culture.

His range is enormous. In his letters he talks about philosophical and metaphysical concepts, about social discourse, poetics, devotion, love and jealousy, human relationships, nobility and pettiness, misery, even matters relating to medicine. And he wrote it all in such a way that we marvel at his intellect and wisdom, even in the 21st century. His superb prose can be parodied, but it cannot be imitated.

In the last twenty years of his life, Ghalib was a vigorous writer of letters. While observing traditional courtesies in these letters, he wrote them exactly as he talked. He as much as announced this in a letter to Mirza Hatim Ali Beg:

"I have invented a style of prose that has turned correspondence into conversation; you can talk with the tongue of a pen at a distance of some two thousand miles and enjoy, while physically separated, the dance of words in conversational union".

* * * * *

Translating Ghalib’s letters into English is not an easy task. Only a specialist who is perfectly at home in Indo-Muslim culture, brought up in the highly educated community of the subcontinent, as well as conversant with the technique of writing classical poetry, with Indian classical music and with the whole way of life of a society in which conversation of a very high level is still considered valuable could undertake this assignment. The late Dr Daud Rahbar was one such person.

Dr Daud Rahbar, scholar, musicologist, essayist, poet and a most unbiased critic, was a polymath. He had a deep understanding of the historical and religious background of Ghalib’s letters that were written during a crucial period of 19th century India, and was capable of a scholarly interpretation of Ghalib’s numerous allusions to political and social events.

In 1969, the year of Ghalib’s centenary, Dr Rahbar, who was then a Professor of Comparative Religions at Boston University, was approached by the Asia Society of New York to translate Ghalib’s letters into English. Dr Annemarie Schimmel, the main instigator of this project, considered this to be an unusually fortunate event, "In him" she has written "We have a scholar who possesses all those qualities which we consider necessary for the translation of a precious piece of Urdu literature."

It took Daud Rahbar (I am doing away with the prefix because he was one of my dearest friends) six years of painstaking work to complete his "Urdu letters of Mirza Asadullah Ghalib" which was then published by the State University of New York Press. It is a definitive study not only of Ghalib’s mind, his extremely fertile imagination, but the historicity of the middle period of the nineteenth century, India. It is a matter of great pride to me that on the first page of the book he wrote "This Translation is Affectionately Dedicated to Zia Mohyeddin and Nun Meem Rashid."

* * * * *

For a Western reader to savour Ghalib’s prose it is vital that he understands the polarity in his character, both in poetry and prose. At one time his writing shows absolute hopelessness and then the gear is changed and the prose flashes up in a joke revealing black humour. The style is majestic one moment and easy going the next. Annemarie Schimmel thinks that if ever a poet had lived up to Lessing’s advice, "Write, as if you were speaking," it is Ghalib.

Daud Rahbar’s annotated English translations of an assortment of Ghalib’s letter offer some excellent specimens of Urdu conversationalisms. The flavour of cultured conversation in Urdu is retained throughout.

Rahbar was brought up by a father (his mother died when he was four) who was a classical scholar of Persian and Arabic. In his boyhood he enjoyed the privilege of being in the company of many elderly personalities whose style of conversation echoed Ghalib’s culture. I am a witness to the manner in which Maulvi Abdul Haq, Hafiz Mahmood Shirani, Syed Muttalibi Faridabadi, my uncle, Dr Mohamad Iqbal (Daud Rahbar’s father) spoke to each other in hushed tones. There were long pauses, and then someone would say something amusing which led the others to chuckle softly. They would even put their hands over their mouths so that their teeth were never visible. Khanda-i-Dandan numa (raucous laughter which bared your teeth) was a sign of bad taste.

But I digress. Ghalib was a man to whom the social graces of life of leisure came naturally. Rahbar makes sure that his translations introduce the leisurely effect of the original. His own cultural heritage was thus an advantage. He has carefully preserved the languor of language which also evokes the period in which they were written. In his preface he says, "The language has to be preserved in the translation so that the reader can feel the luxury of leisure and lounging."

The redoubtable oriental scholar, Annemarie Shimmel, has made a shrewd observation in her Foreword to Rahbar’s book: "Behind Ghalib’s lines lie the wisdom, the charm, and the imagery of nearly a thousand years of Persian poetry and eight hundred years of Muslim rule in the subcontinent. One should not therefore be deceived by ease and casualness that these letters seem to reveal".

Ghalib illustrates the difficulty of achieving something that looks easy in the opening couplet of one of his ghazals:

Bas ke dushwar hai har kaam ka assan hona

Aadmi ko bhi muyassar nahin insaan hona

(it is very difficult for anything to become easy

Even man has not yet attained the status of humanity).

In one of his letters to Mirza Hatim Ali Beg, Ghalib writes:

Such gracefully natural and unconstrained prose was unheard of in the middle of the nineteenth century. The verbal wit and subtle alliteration contained in the two beautifully orchestrated sentences was Ghalib’s gift to Urdu literature. It is not easy to translate these lines into English without being pedantic. Unlike other translators Rahbar does not try to find exotic words to match Ghalib’s word-play. He faithfully conveys the sense of the text intelligibly: "I shall say another thing; although sight to anyone is dear, it is also fortunate that we can hear. While light is monopolised by sight still hearing too, may lead to relationship endearing."

Read the second part here.