A sightseeing excursion that became something more

Autumn in Lahore is such an elusive season. I often forget it exists at all.

If there is autumn in Lahore, it is not the slow smouldering of leaves -- green to red to brown -- or the quiet cooling into a frosty winter. It is a restless uncertainty; sunny mornings turning into cool afternoons, or chilly evenings followed by warm nights. On such days, one might accidentally adopt the nervous inconstancy of the season as their own, and find their mood shifting as quickly as the weather.

On this particular winter morning, during my last visit to Lahore, I sat grumpily sipping coffee while my aunt bustled around me, looking for a hairbrush. She and her husband were taking me on a little outing into the city, to see the tomb of the Mughal noble Ali Mardan Khan.

"I want to go somewhere I have never been before," I had announced eagerly the night before. The harsh light of day, however, had sapped my excitement; all I could think about now was how sleepy I still was, and how much I hated Nescafé coffee. To venture into the rush and noise of city streets felt overwhelming, and I wasn’t sure the monument would be worth it.

I sat sulkily in the backseat as my uncle drove us up G.T. Road, construction cranes slowing the traffic and filling the air with flakes of dirt. We passed a sign for Shalamar Gardens -- we’d gone too far. Up and down the boulevard we drove, looking for the fruit market which would, according to a friend, signal our path. "There," my aunt pointed to our left.

"I don’t see any fruit…," my uncle murmured, turning slowly onto the bumpy dirt lane. But he continued edging his car forward, squinting through the dust that seemed to swirl off the wheels of carts. Motorcycles hurtled by, kids selling socks pressed their patterned wares to the windows, and the car snaked slowly through the jumble. Then the path opened up slightly, and suddenly we were surrounded by carts of fruit.

"This is it," my uncle affirmed, pushing down on the gas. We lurched through the last crowded juncture, and onto a proper paved road right behind the grounds of Pakistan Railways. This was Mughalpura Road, and we realised later we could have turned directly onto it rather than cutting through the marketplace.

I didn’t really mind our unconventional path, though; it made me feel like we had arrived somewhere totally new, someplace far removed from familiar streets and sights.

The tomb, being on railway land, is only accessible via an enclosed walkway, leading from a green gated door on the side of the road. You’d miss it easily if you didn’t know where to look, and it is only open to the public on Thursday mornings.

We stepped into the narrow passageway, which runs for about 300 metres under the railway land. The ceiling is a criss-cross of mesh, throwing patterns of shadow on the walls and floor. Coming from the warm dust outside, the tunnel’s cool air was a delicious chill, and the path seemed to stretch on endlessly into flickering shadow. If you strained your ears, you could hear the noise of the world above faintly through the ceiling. But the distance between there and here, wherever we were, felt infinite. By the time we reached the end, I had that strange, rare feeling of being ready for anything. Not in a brave, willful way; it was more like a quiet acquiescence to all things. I felt like whatever waited on the other side -- good or bad, grand or small -- would all be equal somehow.

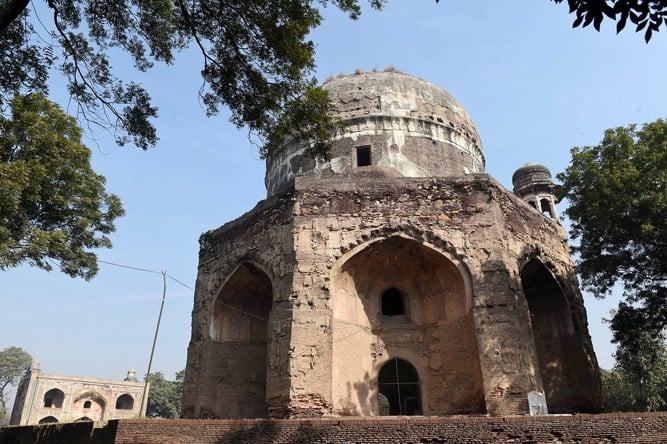

What we found was a grassy compound, surrounded by brick walls. The large octagonal tomb, capped by a large dome, rose up unassumingly from the centre of what must have once been a well-kept garden. We were the only ones there that morning, and as we walked up the steps, my aunt pointed out the remains of marble designs on the walls.

Inside, a cramped stairway leads down to the chamber where the decorated graves of Khan and his mother lie. I would read later about how Ali Mardan Khan, once a Safavid noble, surrendered the city of Qandahar to Shah Jahan in 1638 and came to be known as "Amir al-Umara" (Lord of Lords) as he rose through the Mughal court. I would also learn about his achievements as an engineer, including a canal which brought water from the Ravi River to old Lahore. But that morning, at his tomb, the facts of history faded away, consumed by some other, more powerful sense of time. I stood inside the dome for a only minute, returning quickly to the wild grass outside. I wandered over to the remains of a gateway on the northern edge of the clearing. Here, one can still see the original tile mosaics which once covered the facades.

I passed a goat, tied loosely to a tree, who looked up at me curiously. I said hello, half expecting him to talk back. In this enchanted environment, the bizarre was beginning to seem more and more normal. I saw my aunt sitting down on the steps, humming softly. My uncle smoked a cigarette. The smoke spiraled up, shimmering in the light.

I don’t know how long we stayed. I marvelled at how such a place could exist in the heart of a metropolis. Close by, the world rushed on, but here, everything stood still. I realised that this is part of what gives old cities their charm. It is not just the beauty of seeing the ancient alongside the modern, or the history marked by museums and monuments. It is also these pockets of respite; antique spaces which can take you, if only for a moment, out of time and out of your everyday life. Visiting them can clear a cluttered mind, making room for other things you don’t usually encounter – dreams, fantasies, inspiration.

As we walked back through the tunnel, we began to hear a persistent wail. It came from a young beggar boy, maybe 13 or 14 years old, crying near the doorway. He was mentally handicapped, unable to speak, and stood with his mouth hanging open, tears leaving streaks on his cheeks.

My uncle took out a 100-rupee note from his wallet. The boy refused it, slapping his hand away. My uncle took out a little more. None of us said a word, but we all felt the same distress, the same strangeness of the scene.

The boy took the money, and for a moment, seemed appeased. My uncle patted him on the back, and we walked out into the sunlight. As we stepped into the car, the boy ran up behind us, howling all over again. He stood watching us, crying, as we backed out into the busy road. The car kicked up dust and clouded the windows, and in that final, surreal moment, my aunt lifted her arm, and waved.