Tracing the footsteps of rebels like Kartar Singh and Sita Ramaraju with a rural archivist -- none other than the iconic P. Sainath

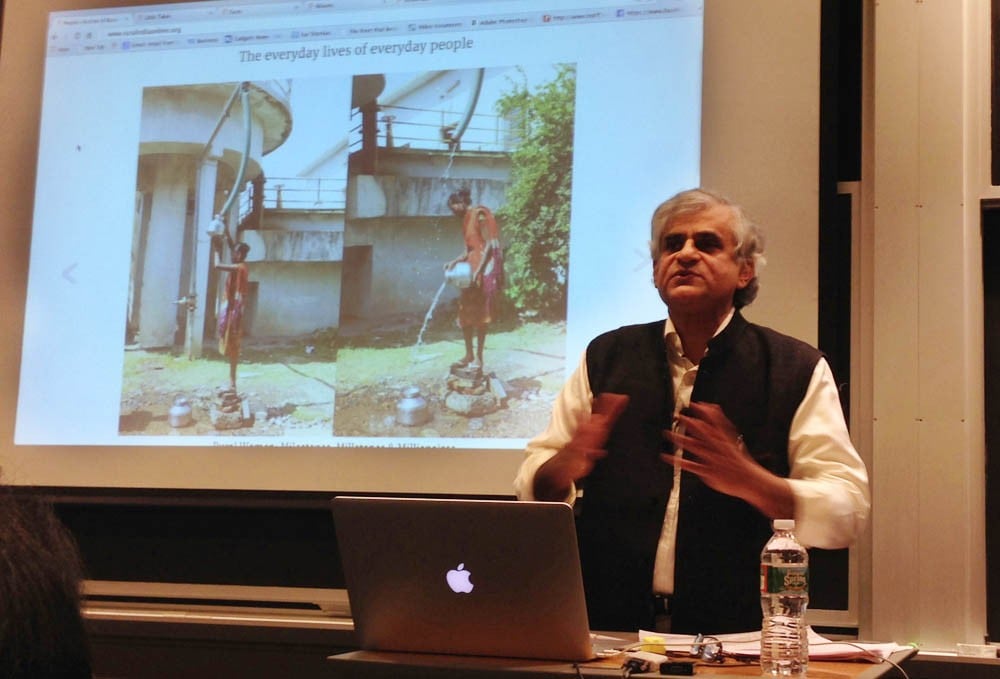

The People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI) completed its first year on December 20, 2015. This ground breaking, volunteer-driven initiative launched by the iconic Indian journalist P. Sainath takes forward his lifetime’s work, providing a platform and trainings to a host of rural journalists, students and activists to document all the facets of their lives that make up the fabric of their society.

More often than not, the mainstream media, with its urban, middle-class focus, ignores or sidelines these aspects. In the process, readers and viewers get an incomplete and skewed picture of the issues that face a bulk of the population. This holds true not just of India but in countries around the world.

I met Sainath (he goes by this, rather than the Pelagummi shortened to the P. in his name) earlier this year. He was teaching at Princeton and had come up to the Boston area to give a couple of talks at MIT that I was fortunate to attend.

I had of course long known of him as the feted author of the best-selling book Everybody Loves Good Drought (Penguin, India, 1996) that highlighted the issue of skewed development and farmer suicides in India. The book, now in its 34th edition, emerged from Sainath’s series of reports after winning a Times of India fellowship in 1993, based on travels around the country living with the poorest communities.

At the talks, he shared his insights and wealth of experience on the lives of India’s working classes. At in-person discussion at a mutual friend’s place later, I learnt that besides occasional visiting professorships at Princeton and other universities abroad, Sainath has long taught at the Sofia College of Journalism in Mumbai and at the Asian College of Journalism in Chennai. The recipient of several awards, he quietly pours a significant portion of award funds and savings back into his work, supporting other journalists as well as families whose stories he takes up. They are not his subjects but storytellers to whom Sainath gives voice.

Through PARI, he also gives them a platform, training them, particularly the younger generation, to tell their own stories.

As we talk, our discussion turns into an eye-opening history lesson for me. Unsurprisingly, this salt-and-pepper haired pioneering rural reporter, as he calls himself, hails from a small village in the south of India, in the "rebel belt" against the British. In fact, "all the great fights took place in rural India, even 1947. They were basically agrarian uprisings," he adds.

The South Asian soldier is "still primarily a peasant in uniform, who comes from a peasant or labourer family and reflects the mood of his village".

In 1997, Sainath did a series of reports to commemorate fifty years of India’s independence. Published in the Times of India, the series highlighted that famine and starvation were the driving factor behind the uprisings against the British.

One of the legendary figures in that fight was a man who called himself Sitarama Raju, who hailed from Sainath’s village. The story of how he came to take on a woman’s name, Sita, says much about this fascinating, unusual character whose real name was Alluri Ramachandra Raju. In 1917, he came out of hiding to attend the funeral of his lady love. There, he announced that he was taking on her name and should henceforth be called Sitarama Raju.

"I can’t think of any other instance when a man has taken on a woman’s name to pay homage to her," muses Sainath.

Not only was the guerrilla commander an unusual man, he came of unusual stock. "Back in1859, his father’s profession is listed as ‘freelance photographer’," says Sainath. His amusement at this classification by the British secret service betrays his eye for the unusual and the caustic dry wit, traits that also permeate his writings.

Sitarama Raju’s family was the South Indian equivalent of the Kshatriyas, the warrior class. Like Sainath’s own family, they were "non-tribals living in an area of tribal misery".

The British were destroying the forests that the Koya tribe of the area depended on -- a pattern that continues today worldwide -- with indigenous peoples still pitted against modern-day colonists, foreign or domestic, in the fight for resources.

A web search for Sitarama Raju later yields Sainath’s article of August 1997, reproduced in PARI. "Many problems of this region that fought the British are as alive today as 75 years ago," he wrote then.

Faced with destruction, the tribals found their primitive bows and arrows pitted against the cannons of the colonists, Sainath tells me. "According to the political agent tracking Sitarama Raju, he disappeared for five years. There’s speculation that he landed up with the rebels of Bengal and Punjab. In 1915 he comes back as a sadhu -- in red -- on horseback. He’s an expert in archery and the martial arts. The British try to buy him out by offering him 50 acres of land in the Godhawari delta. He takes the land and uses it to raise an army, starts harassing the British".

However, Sitarama Raju was very clear about who the enemy was and who should be targeted. He commanded his men "not to bother killing Indian collaborators" -- only armed personnel of the Empire. This is a principle today’s Maoists and other dissidents using similar tactics ignore.

By the time he was 25 in 1921, Sitarama Raju had defeated the British in major battles with bands that never numbered more than 80 people. His guerrilla warfare tactics were studied at Sandhurst a hundred years later, says Sainath.

In 1923 he turned up at the Congress meeting dressed as a Sardar. Sainath’s grandfather (dada) who was present recognised him as a fellow Telugu.

The British began to use feudal tactics, punishing entire villages and brought in the Malabar police, known for their savagery. In 1915, all the able bodied men from villages in the rebel belt were sent off to the Andamans. The colonialists also freely distributed alcohol to undermine the uprisings and demoralise the population.

Looking back, it is incredible how young many of these revolutionaries and rebels were. The most famous of course is Bhagat Singh, only 25 when he was sent to the gallows in 1937.

But he is preceded, and succeeded by so many others whose stories are not as well known though no less inspiring and fascinating, like Kardar Singh Sarabha, one of the founders of the Gaddar party -- only 19 years old when he was hanged.

Kartar Singh was no more than 15 or 16 when taken from the Punjab to the orange plantations of California along with many other fruit-pickers, to break up the Chinese workers’ strike -- "using one group of marginalised against another", to use Sainath’s words.

The Gaddar party grew out of the heightened consciousness of these Indian indentured workers, primarily Punjabis -- "a different kind of NRI" (non resident Indian) as Sainath wryly puts it. "Facing racial humiliation in USA and slavery in India, they were motivated to go back and destroy the empire."

The Gaddar Memorial Hall in San Francisco testifies to their ingenuity and commitment, as I find when I visit the place on a subsequent trip to the city. The Indians, not allowed to buy property, got a sympathetic white woman to buy the original house for them with their savings. The original picturesque building was torn down later. The current Gaddar Memorial Hall is essentially a large room on the first floor (or second, as the Americans call it) of a drab grey building owned by the Indian Consulate. It is open to the public on Wednesday mornings, by appointment only.

A double flight of stairs leads to a landing above a garage with a car inside. A young woman opened the door when we rang the bell. The pungent smell of frying onions and spices permeated the hall. Turns out that Indian Consulate employees live in the building. Several slippers lie on a mat outside a door on the right hand side inside the entrance. The entrance hallway opens into another hallway, lined with framed posters, newspapers and photographs. There are similar artifacts in the large room that lies through a door in this hall.

The British crushed the Gaddar uprising with an iron hand. According to the caption on one of the frames with photos titled "India’s Martyrs" says that they were among the 400 hanged between 1915 and 1916. Photos of some men in a compilation titled ‘India’s Heroes’ says that they were among some 5000 who were imprisoned between 1915 and 1016.

India’s freedom fighters were clearly not just Oxbridge lawyers glorified in our textbooks like Gandhi, Nehru, and Jinnah, but ordinary people, as Sainath points out.

In 1913, Kartar Singh travelled back to India via Ceylon and through Madras back to Punjab -- on a bicycle. He used songs and poetry to incite insurrection in the armed forces. But he was betrayed. The British smashed his network.

"When presented in court, he refused to accept the authority of the judge. This was possibly the most dangerous thing he did," says Sainath.

Rebels like Kartar Singh and Sita Ramaraju may have failed in their immediate objective but their actions lit a candle of anti-imperialism that inspired later freedom fighters like Bhagat Singh.

Many of these stories, originally published in the Times of India, are also posted in PARI’s "Foot-soldiers of freedom" category, including updated information. The website is a wonderful resource that I can see being expanded to encompass all of South Asia. One day.