Aslam Azhar, the father of PTV, has left Pakistan bereft of another sane voice; a voice that was sonorous and resounding

This Christmas eve, he looked cheerful. He took a bite from the cake brought in by his nurse and reminded us that it was a unique occasion when birthdays of the founders of two great religions fell on two consecutive days. He was in a good mood, having recovered from a prostate operation that mostly confined him to his room.

He had become reticent in recent months but that day we got him talking about his school days in Lahore in the 1940s. He reminisced gleefully and shared some anecdotes. Three days later he was no more.

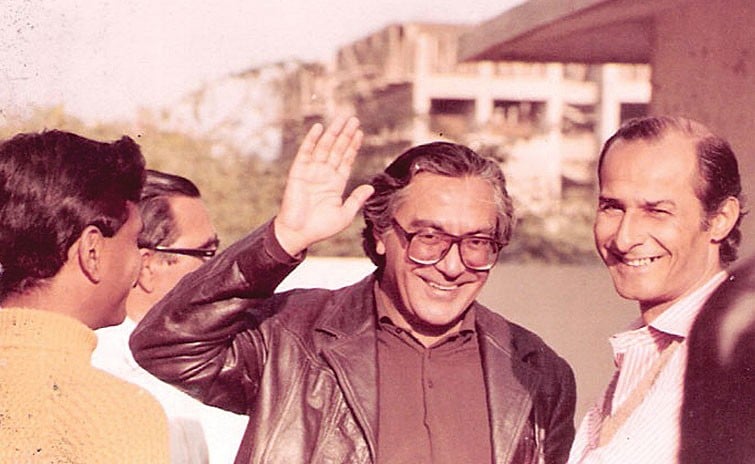

Aslam Azhar, the father of Pakistan Television (PTV), passed away on Dec 29 at the age of 83 and left Pakistan bereft of another sane voice; and what a voice it was -- sonorous and resounding. When he delivered his dialogues as Galileo Galilei on stage in the 1980s, we his trainees at Dastak theatre group tried to emulate him but could never come even close. Dastak had become his passion after his removal from the government job by General Zia-ul-Haq who hated him for his secular demeanour.

Aslam Azhar’s marvellous contribution to establishing and running PTV is well-known. Most of his protégés at PTV have generously acknowledged his contribution; even in November 2015 when PTV celebrated its anniversary, over a dozen retired professionals who had worked with Aslam Azhar in the 1960s and ’70s visited him at home and he sang the PTV birthday song.

What is lesser known is the ordeal that he and his family went through after his removal by Gen Zia-ul-Haq and how he was hounded out of Islamabad. His dismissal was without any pension, gratuity, or any other benefits. With no home of his own to live in and no vehicle to drive, he moved to Karachi and stayed there for almost a decade finding it extremely difficult to survive and maintain his family. But even then he laughed with a stentorian thunder and soon made good friends with Mansoor Saeed. Both shared a loathing for the hypocritical dictatorship of Gen Zia and his coteries.

That was Karachi of the early 1980s. Sindh was a battleground of Movement for Restoration of Democracy. The terror of tyranny was in full swing and entire villages were being decimated by forces of coercion. The so-called jihad in Afghanistan was filling the pockets of rulers and a dismal pall of obscurantism was spread all over the country. In this terrifying atmosphere of public lashings and hangings, there emerged a theatre group that showed a ray of hope to the hapless.

Aslam Azhar and Mansoor Saeed were at the forefront of this theatrical offensive. Plays from Brecht and Chekov to Gorky and Ibsen were translated and staged. Each script had to go the local martial law officers for clearance who had no clue about art and culture and would sometimes mutilate the script and sometimes pass it with some nonsensical changes, especially those concerning any mention of booze.

Aslam Azhar was an inspiring personality with a magnetic pull that could attract and form a team and execute the most difficult of plays in the most daunting of circumstances. Be it an open air play in Bhit Shah at the shrine of Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, or a street play in the labour colony of an industrial area, he could galvanise the Dastak team to deliver a superb performance.

When some of the newcomers at Dastak started calling him Aslam Bhai to show their respect, he insisted he should be called just Aslam. So for most of us he remained just Aslam though the adoration he commanded could not be contained in a word. His tour de force was the stage production of Bertolt Brecht’s Life of Galileo. Aslam not only directed it but performed the role of that astronomer with aplomb. With costumes of the 17th century to wear, telescopes to look for the moons of Jupiter, instruments of torture to frighten the infidel, and the challenge of reciting Latin verses in original to create the fear of the church, it was a difficult play to stage. During rehearsals, Aslam would correct the Latin pronunciation of the actor who was supposed to sentence Galileo.

When the play was presented during the 50th anniversary celebration of the Progressive Writers Association in 1986; the hall would break in applause at Aslam’s heartbreaking pleas as Galileo to the church officials just to be allowed to work as a scientist.

Read also: Aslam Azhar’s last interview with TNS

When Benazir Bhutto came to conditional power in 1988, she persuaded Aslam Azhar to become the chairman of PTV and PBC. He accepted the offer but was thwarted in all his attempts to bring any substantial change. Then he was made an OSD and finally Benazir herself could not survive for long. Aslam joined a private school chain as director but again could not fulfill the owner’s insatiable greed for more profit.

He left that school chain and spent the last two decades of his life in almost seclusion; he would avoid public gatherings and refuse to meet many people.

His last years were almost exclusively devoted to reading a lot. He was a multidimensional giant who could untangle the intricacies of many fields of knowledge. His last public appearance was a couple of years back when he recited Ghalib’s poetry for a select audience at a hotel in Islamabad. When we were taking him to the hotel he was a bit anxious but his wife, Nasreen, was holding his hand and Aslam felt reassured and gave a performance that drew standing ovation.

Nasreen, a human rights activist, and Aslam lived for over half a century together and Nasreen stood by his side through thick and thin. Even as he went from the head of PTV to a persona non grata, Nasreen was always there. Nasreen and their son Arieb took extraordinary care of Aslam during his last days.

Though Aslam did not want to see many people lately, his heart and mind was always open for his Dastak friends whom he considered family. We miss you Aslam.