Unless the world succeeds in cutting carbon dioxide emissions, global warming could trigger far reaching and irreversible changes

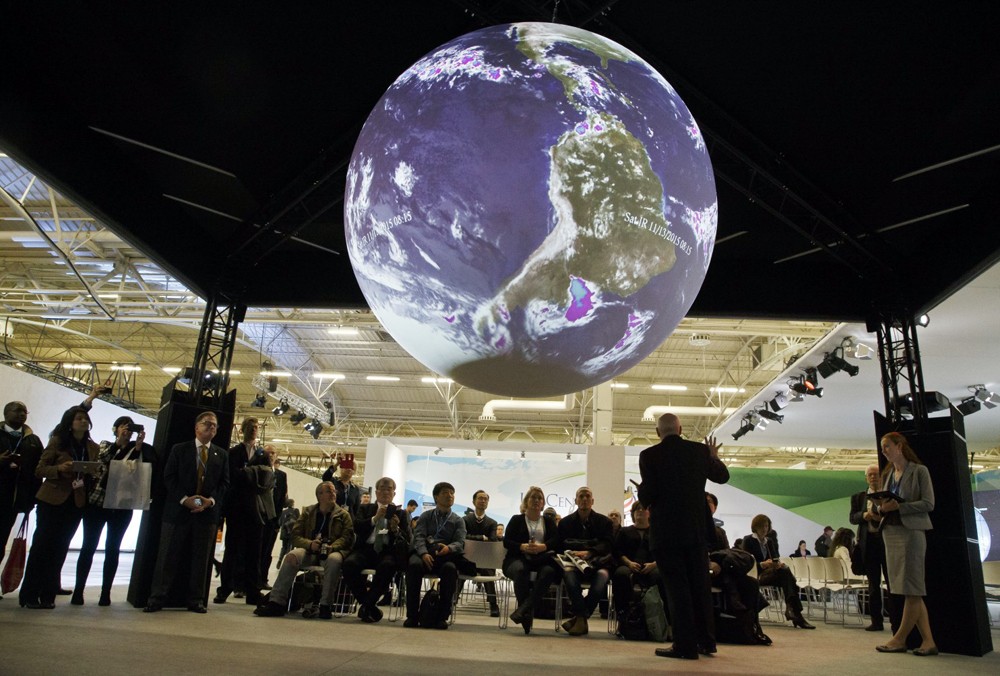

Amidst loud applause and rousing cheers, the envoys of 195 nations approved, on December 12, 2015, the first-ever global accord to tame global warming, calling on the world community to collectively cut and then eliminate greenhouse gas pollution, but imposing no sanctions on countries that don’t. The global community had started deliberations at Le Bourget (Paris: France) from November 30, 2015 under the UN aegis, to define the long-term shift away from fossil fuels towards a low-carbon economy.

The highlight of COP21’s inaugural session was pledges by world leaders to tame global warming. But, scientists say that even if the pledges were fully honoured, Earth will still be on tract for warming far above safe limits. However, in an effort to get countries to scale-up their commitments, the agreement will have five-yearly reviews of their pledges starting from 2023.

On December 1, the bureaucrats of the participating countries scrambled to shape a document that could be approved by the delegates by December 11, 2015 when the conference was scheduled to conclude originally. And on December 5, negotiators delivered a blueprint for a pact to save mankind from disastrous global warming. Finally, with a day’s extension in the duration of the moot, the participating countries approved the pact on December 12, 2015. This pact aims to save the mankind from disastrous global warming, and it would come into force from 2020.

Though not a legal binding, the developed countries agreed to muster at least $100 billion a year from 2020 to help the vulnerable developing nations to cope with the vagaries of climate change.

Unless the world succeeds in cutting carbon dioxide emissions, global warming could trigger far reaching and irreversible changes: raise the number of affected people by 5 per cent, force an additional 100 million people to live in extreme poverty, increase diarrhoea by 10 per cent, disturb the ecosystems and spell the final ruin of some of the precious jewels of nature and civilisation, including the Great Barrier Coral Reef (off the Australia’s east coast), Mount Fuji (Japan) and the canal-crossed city of Venice (Italy).

Climate change and rising temperatures could make diseases like malaria, pneumonia, diarrhoea and malnutrition more fatal. Due to increase in greenhouse gases (GHGs), heatwaves have already become more frequent, causing more severe rashes, cramps, exhaustion and dehydration -- a common cause of hyperthermia and death among infants and children.

Abnormalities in weather could make it more difficult to produce crops, and crop reductions could push food prices up, leading to extreme poverty in most countries. However, the severity of poverty impacts will vary among countries -- with Pakistan, Guatemala, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan and Yemen among the worst hit.

Addressing COP21 on December 8, 2015, Minister for Climate Change Zahid Hamid pointed out that in recent years Pakistan has witnessed the vagaries of climate change with growing regularity and destructive ferocity. "Droughts, desertification, glacial melt, sea level rise and recurrent floods are all manifestations of climate-induced phenomena."

Zahid Hamid identified climate finance "as the core of the battle to confront the adverse impacts of climate change. In Pakistan alone, we require up to US$14 billion annually to adapt to climate change impacts."

Related article: A change for the worst

The nations, however, remained divided over how to give finance for developing nations to cope with global warming: how far to limit planetary overheating; how to share the burden between rich and poor nations; and how to review progress in slashing greenhouse gases.

Pakistan has witnessed devastating earthquakes, floods, cyclones and droughts. The scale of 2010 floods was worse than the 2005 Asian earthquake, which took a toll of 73,000 persons in Pakistan. The 2010 floods in Pakistan, according to UN sources, even eclipsed the 2004 Tsunami and January 2010 Haiti earthquake. An area the size of England was submerged, and over 21 million persons affected in Pakistan outstripped the three million hit by the 2005 earthquake, five million in the 2004 Tsunami and the three million affected by the Haiti earthquake in January, 2010.

The economic cost was staggering: some 1.3 million homes, over 7,000 schools and 8,000 kilometres of rail-road network was destroyed; while millions of hectares of farmland (with standing crops) was submerged, and hundreds of hospitals, dispensaries, factories, bridges and culverts were wiped out. As per government estimates, Pakistan suffered over $20 billion losses due to the adverse effects of climate change. In 2015, the climate change has officially been blamed, for the first time, for triggering abnormal temperature rise and untimely rains in Pakistan’s main cotton-growing belt, leading to about 30 per cent fall in cotton production.

The highlands, in particular, are vulnerable to Glacier Lake Outburst Floods. As glaciers are continuously melting because of rising temperature, by the year 2035 Pakistan will no longer have water reserves in the shape of glaciers, stated experts. Though contributing merely 0.8 per cent to GHGs, Pakistan ranks amongst the 10 most vulnerable countries facing climate changes. If global warming continues, in the next few years, the country might face more natural disasters, like the 2010 floods that consumed the lives of 1,700 people. Though presently floods posed danger to the lives of 23 per cent people, in the post-glacier melt period Pakistan could face an acute water shortage and an increased risk of food scarcity. By 2040, according to WWF, up to 10 per cent of Pakistan’s agricultural output could be affected.

Pakistan’s Indus delta remains exposed to sea rise and sea intrusion, causing an upward shift of almost 400 metres in the coastline. Amongst other damages of global warming, Pakistan is experiencing biodiversity loss, shifts in weather patterns and changes in fresh water supply. The phenomenon of global warming might impact the snow and rain patterns and the availability of snowmelt during summer. Initially, these changes, particularly in patterns of rainfall, glacial retreat and snowmelt, could cause unexpected floods, but subsequently create drought in fertile areas. These changes could accentuate after 2050, scientists forecast.

The global warming, caused by GHGs, is the price of development that the human being is paying. But, the fruits of development have been harvested by the rich developed countries where development activities, factory emissions, modern techniques of agriculture and jet-set life styles are contributing to global warming in a big way. But, developing countries, like Pakistan, with least contribution to this phenomenon, have to bear the brunt of ravages caused by the activities of rich counties.

Low-lying small island states and countries with highly-populated river deltas are particularly vulnerable to rising seas. Some of the small island states could disappear entirely. "As weather patterns change," said US President Barack Obama while meeting leaders of small island states on the sidelines of Paris COP21, we might deal with tens of millions of climate refugees in the Asia Pacific region."

Negotiators for the most vulnerable nations, attending COP21 moot, pushed the world to try to limit global warming to 1.5C (2.4F) over pre-industrial times whereas the world’s powerful nations preferred 2C.

Since 1992 Earth Summit under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), 21 rounds of UNFCCC negotiations have been held, but these failed to give full effect to CBDR (common but differentiated responsibilities). CBDR mandates that the North take the lead in reducing emissions. Since the North is responsible for three-fourths of accumulated GHGs, logically it should also financially and technologically support the poorer South’s climate actions, as required under the Kyoto Protocol that obliged them to reduce carbon emissions to the 1990 level by 2012. Well before the deadline, the developed nations managed to get five years extension under the Durban (South Africa) accord of December 11, 2011.