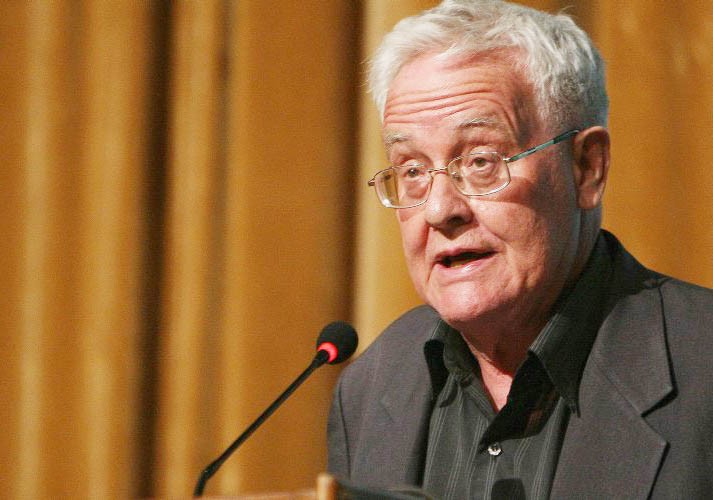

Remembering Professor Benedict Anderson, the most important theorist on nationalism

Professor Benedict Anderson of Cornell University, who has died at the age of 79 in his beloved Indonesia, is widely known for his path-breaking work on nationalism. His magnum opus, Imagined Communities, has been translated into 12 languages and remains an influential text more than 30 years after its publication.

Professor T. J. Clark remarked that great titles are especially dangerous and Imagined Communities is one of the greatest titles. In the two words of the title are embodied a cluster of ideas that are so central to our fresh new perspective on nationalism.

In expounding his theory of nationalism, Benedict Anderson becomes one of the leading theorists of modernist school of nationalism. As opposed to primordialist school of thought, modernists argued that nationalism was the product of interplay of modernist forces of capitalism, modern printing press and literature. Also, nationalism bound together is an imagined political community, contrary to the toxic and insular nationalism of today, mostly represented by far-right, and embraced by the mainstream parties to varying degrees. Anderson saw nationalism as an imaginative process rooted in inclusiveness and outreach, as pointed out by Jeet Heer of New Republic.

In lamenting the lack of significant theorist of the stature of Hobe, Marx and Webber on nationalism, Anderson himself has come to be seen as the most important theorist on nationalism. In fact, one commentator has compared Imagined Communities as the communist manifesto on nationalism. Though Anderson’s scholarly reputation rests on Imagined Communities, he has produced an impressive body of work, equal in significance, and of high intellectual and scholarly merit. His work on nationalism and anarchism in the context of Philippines, titled Under Three Flags, is of immense significance. These two titles suggest where Anderson’s prime research interest lay.

He was an Indonesiaist through and through. Besides his scholarly works on the region, Anderson also exerted himself in the cause of democracy when it was derailed by military coups in the Southeast Asia. His involvement in Indonesia began in the 1960s when he and his colleagues at Cornell University came out with the Cornell Paper.

This famous paper exposed the military coup as a premeditated act by a group of generals rather than a knee-jerk reaction to the fear of the communist revolution. Inevitably the publication led to a long ban on Anderson’s entry into Indonesia which lasted from 1972 to 1998 when General Suharto was finally overthrown. In between, he nurtured his love for South East Asia by turning his attention to another coup-ridden Thailand, where he again dissected the culture of military coups with great precision, prophetic vision and clarity.

Benedict Anderson’s essay, Withdrawal Symptom, published in 1977, is still considered the best study of Thai politics of the 1970s. He also co-authored a collection of short stories in Thai.

Yet Indonesia remained his abiding and lasting love where he has legions of admirers and mourners. He taught himself Indonesian languages and acquired sufficient proficiency to joke and think in the language. He also adopted two sons from Indonesia.

My knowledge and interest in the work of Benedict Anderson was further amplified by my connection with him forged during a conference on Cosmopolitanism and the Nation State in Patna in 2003. Like all delegates to the conference, we hung out in proximity of Benedict Anderson, who was the star speaker at the conference. By sheer luck, he was my neighbour in the hotel where all delegates were housed. We invariably shared the breakfast and lunch table during the conference where Professor Anderson shared his vast knowledge of the South East Asian politics, nationalisms and military coups of various stripes. Anderson would ask me searching question about the Pakistan politics and the military coup in particular.

Like a true scholar, he wanted to learn as much as he could from the people of the region. I explained the current situation as much as my knowledge allowed. But it was Anderson who had more insight on Pakistani politics than me, and would invariably draw comparisons between Pakistan and Indonesia, in terms of shared history of military coups.

I found his knowledge of Pakistan as deep and as insightful as of Indonesia and South East Asia in general. I can say that I learned more about the comparative trajectories of military coups in Indonesia and Pakistan from him than the scores of books I had read before.

Yet despite his vast knowledge, he was unpretentious, warm and engaging. In the decades or more since, my own thinking on politics and nationalism is still being continually shaped by conversations I had with him during the conference and his subsequent works.

Benedict Anderson was born into an Anglo-Irish family in China in 1936. His father James Anderson was the Customs Commissioner in the service of the Chinese administration. His brother, Perry Anderson, has written movingly of the father’s stay in China and of the Anderson family. In 1941, the Anderson family moved to the US because of the impending Japanese advance on China.

Benedict Anderson grew up in California and was educated at Cambridge and Cornell. His Marxism was honed while he was a student at Cambridge during an era of anti-colonial movements and political ferment. This brush with the historic epoch was to shape his political worldview deeply marked by Marxist and anti-colonial thinking.

The Andersons have lived a peripatetic existence. The family moved back to Ireland in 1945 for a brief period only to realise the strain of multiple belongings. However, this nomadic existence was a blessing in disguise because the peripatetic life was to instill in the Anderson sibling an international and global outlook.

Not comfortably anchored anywhere in the world, the Andersons have lived in languages, ideas, theories and global movements. The family’s legendary global-mindedness and instinctive multi-lingualism has led Jeet Heer of the New Republic to describe him as a man with no country. The Anderson clan is truly global and internationalist in outlook and intellectual sympathies, fluent in most of the European and South East Asian languages. Benedict’s younger brother, Perry Anderson, is a formidable historian in his own right. Another sister, Melanie Anderson, fluent in many languages too, is a distinguished anthropologist.